“Are you Jewish?,” I asked the hostess of the paladar we entered.

She looked up, confused, and handed us menus.

I pointed to the silver star of David around her neck.

The hostess laughed. “ You know, only tourists ask me that,” she said. “I just really liked the design of it. I don’t even know what it means.”

Source: The New York Times

This wasn’t the answer I was expecting. Were the stories of a remnant Jewish community in Cuba just another incitement for tourism, a commercialization of a religion as a way to bring hard currency into a floundering economy?

Such began the long and muddled journey for what I would learn about Judaism in Cuba. From the Jewish themed hotel we saw in Old Havana to Yoel’s occasional mention of Cuba’s Jewish community in the context of Alan Gross, the supposed “revival” of Judaism in Cuba was difficult to comprehend.

To understand Cuba’s contemporary Jewish population, we must first understand the history of Jewish migration in Cuba. The first Jews to arrive were not practicing Jews, but rather conversos, Spanish Jewish converts torn between their Jewish ancestry and Spanish identity. Under the Spanish empire, these Jews could only practice in secret, and thus, it was difficult for them to continue their religious practices. Only following the abolition of slavery in Cuba and the fall of the Spanish empire was it possible to establish the foundations of a Jewish community in Cuba.

American Jewish expatriates were the first practicing Jews to arrive in Cuba. Other Jewish immigrants gradually siphered into Cuba–Sephardic Jews from Turkey, Askenazic Jews from Poland (so many in fact that many Cubans adopted the term “polaco” or pole, to refer to Jews in general), and Jews that were brought in out of the desire of Cuba’s elites to “whiten” a Cuba that had become too dark following independence.

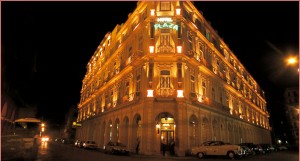

A photograph taken at Hotel Raquel, the Jewish themed museum our tour stopped at.

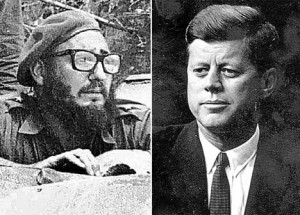

In the 1960s and 70s, synagogues in Havana and Santiago de Cuba were kept alive with monthly membership fees, money the government paid to rent the space, and the yearly sale of Passover goods. The Canadian Jewish Congress, replacing the marred diplomatic relations between Cuba and the United States, also delivered Passover goods to Jews who registered for them. Unfortunately, by the 1980s, many Jews decided to detach themselves from religion, integrating into the Cuban ideology of national unity. This diminished the prospects of continuity for Judaism. Under Castro’s rule, it was difficult for Jews to find religious texts and kosher foods.

Despite these odds, in 1992 amidst religious openings in Cuba and the United States’ encouragement to send religious missions to Cuba, the Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) was founded. This paved the way for various other Jewish organizations such as B’nai Brith, Hadassah, and Hillel. This resurgence of a Jewish community in Cuba, under the idea that all Jews are part of “one people”, resulted in the contemporary Jewish communities in Cuba. Many of the Jews currently in Cuba are recent converts; they sought to find their religious roots and determine their identities.

Cuba has a current Jewish population of about 1,500, far fewer than the 15,000 that existed prior to Fidel Castro’s usurpation of power. The Jews currently residing in Cuba must be very aware of their financial dependence on the larger Jewish community. There is no rabbi on the island and there is only one kosher butcher. With their salaries averaging roughly $20 a month, adhering to Jewish traditions and surviving on a day to day basis is challenging.

Many outside Jewish entities organize religious trips to Cuba, where they are often scheduled with a set of religious and humanitarian activities that often include the donation of clothing, medication, and objects for prayer. To me it sometimes seemed as if Cuba was exploiting this fact, and using religion as a tourism export or as a way to obtain hard currency. The influx of Jewish dollars and donation, though well intentioned, provides help for a small sect of the Cuban populace solely because of their religion. The majority of the capital to support the synagogues, purchase kosher foods, pay for medicines and cover the costs for Shabbat meals comes from the United Jewish Communities. The Cuban Jewish economy economy is bolstered by the Jewish community, including Jews who fled Cuba and have been sending funds since.

Despite it not being a focus of our trip, it was easy to see tenets of Judaism manifest themselves into the Cuba we, as tourists, were exposed to. The Hotel Raquel we stopped at, catering to the needs of Jewish tourists, is one example. Similarly, the night I went out to Teatro Bertolt Brecht with Jonah and Isabelle, I learned that the building of the theater itself used to be part of the Patronato (Havana’s main synagogue). Half of the synagogue’s original structure was sold to the Ministry of Culture during the years of the Revolution when religious participation was low. The actual synagogue, that today is a fully functioning synagogue that actively receives international Jewish tourists, is right next door. This location is quite popular for tourists, and, thus, another example of how Cuba’s Jewish community centers its locations of worship in touristic areas.

According to Yoel, the Cuban government is very accommodating to the needs oF the Jewish community. It doesn’t interfere in the business practices of the one kosher butchery in Havana, the distribution of matzah during Passover, and the frequent departures of Cubans to Israel ( often completely funded by the larger Jewish community). Many Cubans are incentivized to convert to Judaism because it gives them a greater chance to leave. Israel and other private Jewish organizations traditionally cover the immigration costs for Jews from isolated locations. This stems from an effort to illustrate how Israel is a haven for Jews all over the world, despite financial differences.

The cover image from one of my sources, a book by Ruth Behar titled, "An Island Called Home: Returning to Jewish Cuba". It depicts the temple entrance of the "El Patronato" synagogue in Havana.

It is difficult to say that the revival of Cuba’s Jewish community is solely due to the incentives the larger Jewish community provides, but it is something that must be brought into question. Although the survival and perseverance of Cuba’s Jewish community is both admirable and miraculous, how much of it is rooted in what the larger Jewish community can offer Cuban Jews?

Sources:

Behar, Ruth. An Island Called Home: Returning to Jewish Cuba. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2007. Print.

Gerszberg, Caren Osten. “In Cuba, Finding a Tiny Corner of Jewish Life.” NYTimes.com. The New York Times, 04 Feb. 2007. Web. 20 Apr. 2012.

Millman, Joel. “Rites of Passage: In Cuba, a Revival in Judaism Leads Some to Israel.” The Wall Street Journal Online. The Wall Street Journal, 14 Jan. 2009. Web. 22 Apr. 2012.

Industriales’ Mascot

Industriales’ Mascot