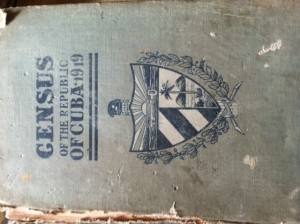

“¡Hola! ¿Cómo están chicas?” An amiable address from the smiling bookstore owner welcomes us as we slow our stroll through Cienfuegos and peer into his shop. To allow us inside, the owner, Anabel, has to move the front display table back from the doorway. We squeeze into the small anteroom filled with Cuban books, posters and other chachkis. “¡Oh, Americans!” he exclaims with surprise and genuine enthusiasm. He begins guiding us through the books stacked on shelves and tables. Among these are copies of Garcia Marquez, books in French and English, and highly valuable Cuban Census books from the early 20th century. This shop is his aunt’s house, he tells us. He pays her a small sum of money each month for rent. She can be seen in the room just behind the store, sitting in a rocking chair, endearingly calling Anabel’s attention to new customers.

Entering businesses like this in Cuba requires a certain level of proximity to the owner’s personal life that we are not used to in North America. It can feel a little invasive, but most privately owned businesses in Cuba are run out of people’s homes, or more specifically their living rooms so we had to get used to shopping and eating in peoples’ homes.

Anabel is eager to talk with us about himself and Cuba. We unleash our curiosity that has been building up for the past two months.

He was an actor, a professional who earned a government salary, until five months ago when he decided to open the bookstore. He spoke about acting the way one talks about a relationship with an inevitable end. He said he missed it a lot – it was his passion, but the salary was not enough, like so many other Cuban jobs.

From few people I was able to have a conversation with in Cuba, I got the sense that many felt like this man had five months before. Now that Raul Castro has opened up the economy to allow private businesses like Anabels’, there has been a significant increase in restaurants (paladares), taxis, and clubs – many of which cater primarily to tourists. With this new sector, there are more career options for Cubans (although this is easier for Cubans receiving remittances). Some have come to accept that their lives are made difficult by insufficient food and low wages, so they figure that doing what they love and what makes them happy is the best they can do. Others, like Anabel, are tired of the government salary and have taken advantage of this opportunity to make more money, even if that means stepping away from their skilled professional job. Although he misses acting, Anabel is happy with his new business.

His shop is popular. I suspect it’s because of his friendly demeanor and genuine smile – personable qualities which he tells us are seen less frequently in employees of the state sector.

During our visit the shop attracts three Cuban customers, asking for books on beginning French and English, reiterating the emerging influence of tourism on Cuba. Anabel tells us that learning languages is becoming more and more important for Cubans, especially those wishing to work in tourism.

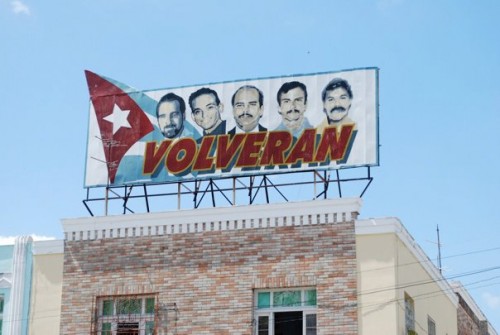

To me, this shop exemplifies Cuba’s “Transition” phase. When we ask Anabel what he thinks will be the impact if the embargo is lifted, he asks us to speak in English because he doesn’t want people around him to hear. Most of what he says is positive, and he talks about the hope that some Cubans have and will have if Obama is reelected.

The Cubans we got a chance to speak with are generally hopeful about lifting the embargo. They were not filled with idealistic pictures of the U.S.A. as they are well educated and understand the problems with our system. But they all acknowledged that their everyday struggles could be ameliorated by trade with our country.

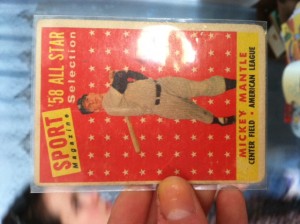

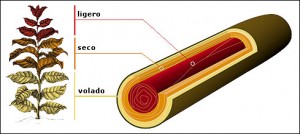

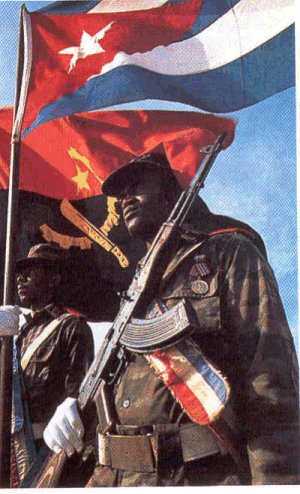

As a tourist, I both understand this point of view, yet also wince at the thought of U.S. tourists flooding Cuban streets as more and more cheesy souvenir shops pop up to accommodate their desires for “Cuban” things (cigars, Che posters, etc.). Glancing around this bookstore, what I hope is that places like this can exist and prosper without turning into the shops solely dedicated to tourism. I hope that insufficiencies in Cuba can one day be alleviated by trade with the U.S., but that this trade and lifting of the embargo does not completely compromise the vibrant Cuban culture.

Posted in Uncategorized | No Comments »