As a student of history, I have leaned about many different revolutions. Few have been truly successful, with success being defined as long-lasting and without extreme violence being necessary post-revolution in order to keep the new government in power. Most modern revolutions have ended in massive bloodshed, often on the level of genocide. I would never say that the socialist revolution in Cuba has been perfect or that it is without doubt what is best for the Cuban people but watching ¡Cuba Va! and going through the readings on Cuba’s post-revolutionary development, I can say one thing for sure: the Cuban revolution is fully their revolution. That is something that cannot be said about the other countries that ideologically fell in line with the Soviet Union during the twentieth century.

It is true that the growth of communism in Eastern European countries that ended up under Soviet control, such as Poland and Czechoslovakia, was primarily driven by ideologues who believed that communism offered the best chance at equality for all people in addition to being the political system with the best chance at preventing fascism from ever returning. However, whatever autonomy these countries had was extremely short lived. The will of the Soviet Union was enough to turn idealists into cynics as the Stalinist trials swept through Eastern Europe. Thousands of innocent people were thrown into jail for supposedly going against the party and remained in jail for years. Many were sentenced to death or were treated so badly that they died shortly after being released. No one could be in a leadership position without the approval from Moscow. Communism that wasn’t Stalinism was simply unacceptable.

Stalin's Statue in Prague

Despite Cuba’s almost total economic dependence on the Soviet Union for the first thirty years of the revolution, Cuban socialism is certainly not Russian communism. This is partially due to Castro’s initial reluctance to officially join the communist party in Cuba – he believed it was antiquated and corrupt like most other established parties – and due even more, in my opinion, to the fiercely independent Cuban political spirit. He was only incited to officially declare himself and therefore the Cuban government as socialist when it became clear that the Unites States was blatantly trying to destroy the revolution.

What set the Cuban revolution apart then and what continues to set it apart now – other than the fact that it survives, unlike communism in Europe – is widespread support from the people. This is due in no small part to the ability of the people to debate, discuss and take part in the development of their country. Obviously, there is massive censorship in Cuba; speech is by no means free. Yet the images we sawing ¡Cuba Va! of young people engaging in vigorous debate in the middle of the street shows not only a lack of terror of the government but a commitment to the success and development of the revolution.

Youth arguing in Cuba from the film ¡Cuba Va!

After all, the need to debate or argue goes away if one no longer cares or believes in the success of the nation. Cuban passion for the revolution comes from the beautiful nature of the ideals of equality in communism which is in line with the ideals of Cuban hero Jose Martí. Furthermore, the unlikely nature of the revolution’s success goes a long way to cultivate pride in the people.

It was a revolution led by a few who should not have been successful against anyone, much less against an American-backed dictator. Victory against the epitome of a capitalist society is extremely important to the Cuban peoples’ view of their own history and in the Periodo Especial, it has helped sustain the people in a time of great flux with many lingering questions about the future of the country.

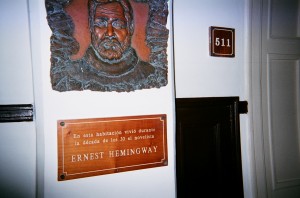

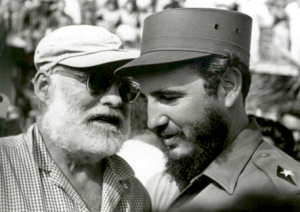

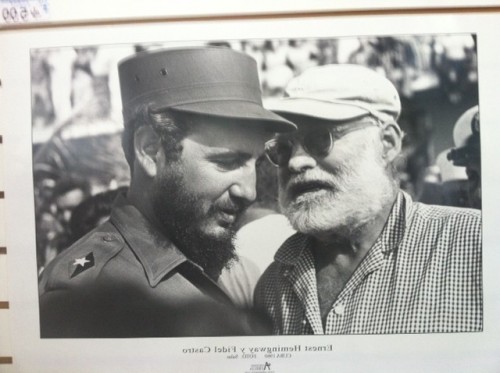

Cuban loyalty to the ideals of these two men has helped sustain the revolution through it's hardest times.

The faith and passion among the youth has waned to a certain degree. Many authors and scholars have commented on the strange reality of young people who are living with the unkept promises of the revolution, especially as tourism grows making some people wealthier than others, especially those who are lighter skinned, particularly problematic in a theoretically raceless society. Yet despite their doubts and frustrations, they are still joining the party, still marching in parades and declaring their commitment to “el socialismo o muerte.”

It is not perfect in Cuba. Many people are angry and disillusioned. The government violates basic rights such as free speech regularly and it has a history of imprisoning supposed political prisoners. Yet there is something really beautiful and admirable about what they have tried to achieve: an equal society where all the people have enough and everyone works for the well-being of everyone else, not just their own. No one can know if the socialist revolution will continue in Cuba or what shape it will take in the coming years. If it does survive, it will be because the people choose to protect it and stand by it, because they believe in it and take pride in it. Raul and Fidel and the memory of Che will not be enough.

Posted in Uncategorized | No Comments »