Homosexuality in Contemporary Cuba

May 4, 2012 by sptilger

The place of homosexuality in Castro’s Cuba has been a complicated and much contested one. When the Revolution triumphed in 1959 and began its project of creating a revolutionary society, homosexuality had no place in the new Cuba. Building from a long history of Cuban machismo that traces its origins to colonization, the Revolutionary government initially actively persecuted homosexuals. From 1965-8 many gay men and women were even sent (along with other Cubans who did not fit revolutionary standards) to forced labor camps known as UMAP for rehabilitation (Larson, 63). As late as the 1980s Cuba was harshly criticized for its program of forced quarantine of AIDS victims, who were mostly gay men. However, more recently, Mariela Castro has made it her personal mission to reverse this previous injustice and ascertain equal rights and protections for homosexuals through her position as the head of CENESEX, which was established in 1989. One of their major successes has been passing a bill that includes sex change operations as part of the free national health care system. Presently, Legalizing civil unions for same-sex partners is one of CENESEX’s top priorities, as is legalizing gay adoption. (CENESEX talk, 2012).

An official CENESEX video against homophobia

Professor Scott Larson, a scholar on gay space in Havana, writes that public spaces like the Malecón, Parque Central, and La Rampa all serve as meeting spaces for gay Cuban males. He emphasizes the importance of public space in a socialist society where until recently the government owned all property (Larson, 70). In capitalist countries gay neighborhoods (or “gay ghettos”) have historically emerged as centers of gay culture and community with privately owned gay businesses providing social spaces for these marginalized populations. Since this has not been a possibility in socialist Cuba, queer men and women have had to find alternative methods of expressing their sexuality, often appropriating public space for their own uses.

During our brief stay in Santa Clara we met with the founder of the Centro Mejunje, a sort of government-funded community center in the city of 237,580 people that focuses on the “inclusion of everyone.” The center was founded in 1984 and was an important part of the beginning of the gay rights movement in Cuba. Currently it is not an exclusively “gay place” but existing as a welcoming place for gay people is an important part of its identity and activities. There have been significant improvements in the life of the gay residents of Santa Clara as a result of the center. The center helps reunite families who have kicked their gay children out of the house, and have even gotten police harassment to stop. Unfortunately, however, Mejunje is fairly unique in Cuba and similar centers do not exist elsewhere in the country. Additionally, we can infer from his remarks that significant police harassment of queer Cubans still persists outside of Santa Clara (Mejunje interview, 2012).

As an alternative to centers like Mejunje, the director of that program mentioned that a few gay clubs have recently opened in Havana and other provinces. Our guide Adriana also mentioned that the government recently transformed an abandoned movie theatre in Havana into a gay club/space for gays to meet and hang out. She also said there are a few bars that while not officially “gay bars” are known for having a significant gay and lesbian clientele. It is important to note that the bar she specifically mentioned is a paladar, which goes back to Larson’s point about the role of private property in creating gay space. Raúl Castro’s reforms are causing sweeping changes in Cuba, and I wonder how the legalization of private property and enterprise will affect the position of gay and lesbian Cubans. It is too early to make any judgments but I am concerned that any new permanent gay spaces that emerge as a result of free enterprise will be raced and classed due to the inequalities in which Cubans have access to hard currency and can thus frequent those establishments.

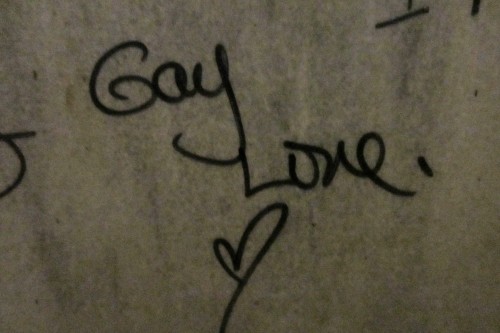

As to the position of homosexuals in general, Adriana’s opinion was that Cuba is becoming a much more accepting society largely thanks to CENESEX’s work, but that “it takes time for a culture to change.” When I went to a club my last night in Havana with the rapperos I found this graffiti, which to me was an indication, however small, that the culture is indeed changing.*

*However, note that it is written in English, not Spanish.

Sources

Interview with Adriana at Hotel Ancón, March 2012

Talk with an official representative of CENESEX, March 2012

Talk with the founder of the Mejunje Center in Santa Clara, March 2012

Larson, Scott (2010). Gay Space in Havana, in The Politics of Sexuality in Latin

America: A Reader on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Rights, Javier

Corrales and Mario Pecheny, eds. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, pp.

334‐348

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.