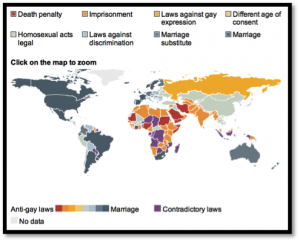

From the outrage at the Sochi Olympics over Putin’s “propaganda” law to Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Act, it’s clear that strong anti-LGBTQ climates exist globally. But few Americans realize how many countries still oppress gay rights: the BBC estimates there are about 77 countries that currently have anti-LGBTQ laws in place (BBC 2014).

As a result of hostile climates in home nations, many LGBTQ adult and child immigrants seek political asylum in the United States. LGBTQ children may not just be fleeing oppressive laws, but also escaping families or communities that shun them for their sexual orientation. They are disproportionately represented among the unaccompanied minor population, making up 19% of immigrant children in foster care and 12-15% in the juvenile justice system (Gruberg and Hussey 2014:2). But flaws within the U.S. immigration system have major effects on LGBTQ child immigrants, who often fall between the cracks of immigration services and systems. The major issues they encounter include: higher levels of abuse in detention centers; increased harassment in shelters by authorities and peers; and greater problems proving eligibility for asylum.

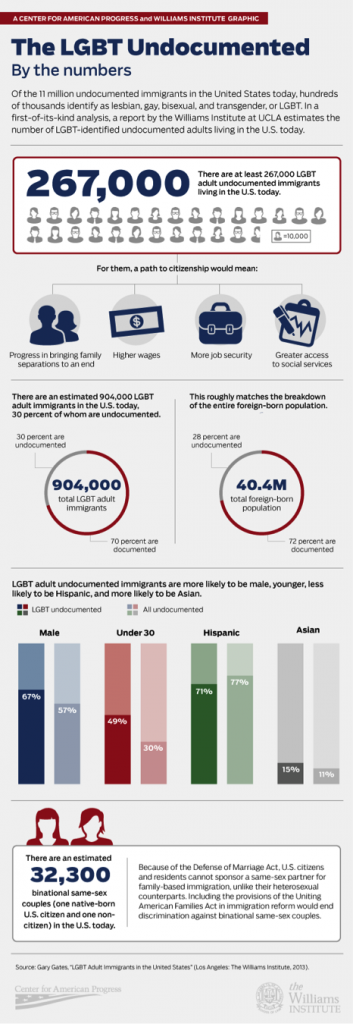

Figure 2. The LGBT Undocumented by the Numbers. (Click for full resolution.) Source: Center for American Progress and the Williams Institute (2013)

267,000 adult LGBTQ undocumented immigrants live in United States today; that number likely skyrockets when youth are included (Gates 2013: 1). Because they were considered “sexually deviant” under older laws, openly LGBTQ immigrants were excluded from coming to the US until the 1990s, when the Immigration Act of 1990 opened the path for a larger immigrant flow to the United States.

If LGBTQ immigrants apply for political asylum as a defense against deportation, they are almost always placed into detention centers until their cases are settled. Both children and adults can be placed in detention, though children are more often placed in foster or shelter care. Detention centers have notorious history of “housing immigrant minors in disgraceful conditions without access to education, health care, legal services, or other basic necessities” (Navarro 1998: 590). Conditions for LGBTQ child immigrants are even worse, since they suffer greater verbal and sexual abuse: LGBTQ adult detainees are about fifteen times as likely to be sexually abused as heterosexual detainees (Gruberg 2013:1). Though there is little data on LGBTQ children in detention, they likely face similarly high abuse, and detained children have reported incidents of sexual assault by other detainees and guards (Navarro 1998:600). LGBTQ youth have also reported being “punished for behaviors that their heterosexual counterparts engage in without repercussion…are encouraged to “change” their sexual orientation or gender identity; and are prevented from or disciplined for expressing their gender identity” (Gruberg and Hussey 2014: 2-3). Transgender child immigrants may face authorities who ignore their gender identities and detain them with their non-identifying sex (Gruberg 2013:4).

Detention centers have also historically “restricted immigrants’ access to healthcare” (Androff et. al 2011:89). These restrictions especially affect LGBTQ child immigrants since they may have specific medical needs, foremost among them mental health care. Because they are refugees fleeing violence, many of the children suffer psychological damage such as PTSD – but still, “access to psychiatric care is a frequently cited problem at INS detention facilities” (Navarro 2011:602). LGBTQ children may also need access to medicine such as HIV/AIDS medication or hormone therapy. If basic medical needs are hard to access in detention centers, obtaining specialized medical care will be difficult.

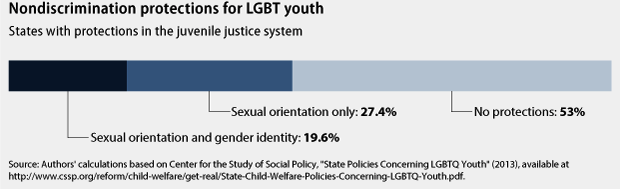

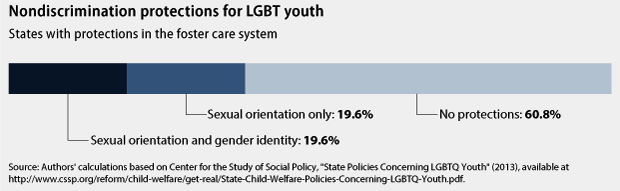

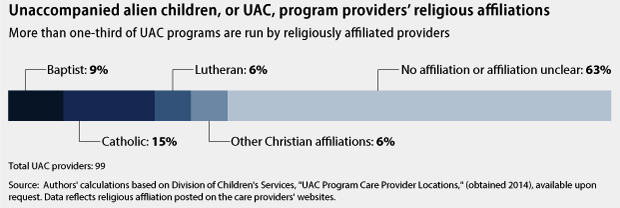

LGBTQ unaccompanied minors who do not go to detention centers often go to shelters (80%) or foster care (11%) (Byrne and Miller 2012:15). While conditions there are less restrictive than detention, 70% of LGBTQ youth in shelters report violence against them and 100% report verbal harassment based on their sexual orientation (Gruberg and Hussey 2014: 2). Institutional policies towards LGBTQ youth are inconsistent, especially because Christian-affiliated institutions – whose agendas range from all-inclusive policies to conservative views – run just over a third of homes for unaccompanied minors (Gruberg and Hussey 2014:5). Many crimes in shelters go unreported because “undocumented immigrants are significantly less likely to report being victimized” (Androff et al. 2011:89). Additionally, shelters have no standard grievance reporting process, making it difficult for LGBTQ youth to file complaints (Gruberg and Hussey 2014:5).

Figure 3. Protections for LGBT youth in the juvenile justice system. Source: Center for American Progress (2014)

Figure 4. Protections for LGBT youth in the foster care system. Source: Center for American Progress (2014)

Figure 5. Unaccompanied minor program providers’ religious affiliations. Source: Center for American Progress (2014)

LGBTQ youth encounter more difficulties when applying for political asylum, a legal process that allows refugee immigrants to stay in the United States. Minors may also apply for Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) status if they “are found to be dependent upon a state juvenile court and…return to their home country is contrary to their best interests” (Lloyd 2005:238).

For any unaccompanied minor, the process of applying for asylum or SIJ status is difficult: immigration law falls under federal-level rule, but juvenile law falls under state-level jurisdiction, leading to friction between the federal and state courts. As a result, federal courts often have to handle children’s issues, for which they are untrained (Lloyd 2005).An initial obstacle lies in access to legal counsel: in detention centers, children have been “afforded little access to legal assistance, telephones, or other means to prepare their legal cases” (Navarro 1998:600). For example, detention authorities have limited children’s contact with lawyers, or have monitored calls (Navarro 1998:600). Immigration officers are also ill-equipped to handle children’s psychological needs, and so “many child victims of abuse and abandonment were retraumatized in immigration interviews in which untrained immigration officers asked child victims for details of their abuse and abandonment” (Lloyd 2005:246). Finally, children’s cases can bring up special difficulties. Generational issues may lead to miscommunication; children may view “fear of persecution” on a different basis than adults; they may forget specific details due to age; they may be intimidated by the court setting; or they may suffer from such trauma that they have trouble reliving their experiences in a public setting (Bhabha and Schmidt 2006:121-122). Therefore, cases become dependent on the presiding judge’s policies, and the asylum decision becomes a nearly arbitrary process because it lacks regulation.

LGBTQ youth face more challenges because to prove asylum, they must not just prove persecution, but also prove that they identify as LGBTQ. Because their identification is not marked by a physical trait as with age or race, proving non-heterosexuality becomes a messy process. Judges may be further skeptical about the ability of LGBTQ minors to identify as LGBTQ, given their age. Again, a lack of guidelines for LGBTQ youth complicates the asylum process.

Finding asylum in the United States is a trying experience for all immigrants, especially for refugees fleeing dangerous home environments. LGBTQ unaccompanied minors fall at an especially high risk for abuse and neglect but are often overlooked, which is why they need specific guidelines and services that cater to their needs. Many of the crucial changes will not occur until the US fixes some overarching problems in its immigration system: providing detention center and shelter accountability, sufficient resources for detainees, and legal guidelines on a federal and state level for child immigrants, with a clear policy establishing that “children are children first and potential immigrants second” (Lloyd 2005:261). The United States needs to follow more just and humane policies, not the broken, underequipped system it currently operates (Androff 2011:93). And until this country shows that it cares about all its immigrant populations, including LGBTQ children, it cannot call itself a nation with any justice.

References

Androff, David K, Cecilia Ayón, David Becerra, Maria Gurrola, Lorraine Salas, Judy Krysik, Karen Gerdes, and Elizabeth Segal. 2011. “U.S. Immigration Policy and Immigrant Children’s Well-being: The Impact of Policy Shifts.” Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare 38(1): 77-98.

BBC News. 2014. “Where is it illegal to be gay?” Published February 10. Retrieved October 22, 2014. (http://www.bbc.com/news/world-25927595)

Bhabha, Jacqueline and Susan Schmidt. 2006. “Seeking Asylum Alone: Unaccompanied and Separated Children and Refugee Protection in the U.S.” Cambridge, MA: University Committee on Human Rights Studies, Harvard University. Retrieved November 14, 2014. (http://www.law.yale.edu/documents/pdf/Clinics/Seeking_Asylum_Alone_US_Report.pdf)

Byrne, Olga and Elise Miller. 2012. “The Flow of Unaccompanied Children Through the Immigration System: A Resource for Practitioners, Policy Makers, and Researchers.” New York: Vera Institute of Justice. Retrieved November 14, 2014 (http://www.vera.org/sites/default/files/resources/downloads/the-flow-of-unaccompanied-children-through-the-immigration-system.pdf)

Gates, Gary J. 2013. “LGBT Adult Immigrants in the United States”. The Williams Institute at UCLA School of Law. Retrieved October 22, 2014. (http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/wp-content/uploads/LGBTImmigrants-Gates-Mar-2013.pdf)

Gruberg, Sharita. 2013.“Dignity Denied: LGBT Immigrants in U.S. Immigration Detention”. Washington, D.C.: Center for American Progress. Retrieved October 21, 2014. (http://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/ImmigrationEnforcement-1.pdf)

Gruberg, Sharita and Hannah Hussey. 2014. “Fostering Safety: How the U.S. Government Can Protect LGBT Immigrant Children”. Washington, D.C.: Center for American Progress. Retrieved October 21, 2014. (http://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/GrubergLGBTUACBrief.pdf)

Lloyd, Angela. 2005. “Regulating Consent: Protecting Undocumented Immigrant Children From Their (Evil) Step-Uncle Sam, or How to Ameliorate the Impact of the 1997 Amendments to the SIJ Law”. Public Interest Law Journal. 15: 237-261.

Navarro, Lisa Rodriquez. 1998. “An Analysis of Treatment of Unaccompanied Immigrant and Refugee Children in INS Detention and other forms of Institutionalized Custody.” Chicano-Latino Law Review. 19:589-612.