During the summer of 2014, the American public was inundated with the news of a crisis at the southern border. An unprecedented number of unaccompanied Central American youth had been crossing into the United States, many surrendering themselves to border patrol agents immediately upon arrival. Pundits and politicians were quick to judge the crisis as another manifestation of a broken immigration system, exacerbated by an inept or malicious presidential administration that was systemically failing to enforce the law. Amid the storm of partisan squabbling and heated rhetoric, countless images emerged documenting the plight of unaccompanied minors, from their arduous journey to the United States to the inhumane conditions they encountered at detention centers after their arrival. The experiences of these children have been heavily politicized and distorted, shrouded in misinformation and prejudice. In order to fully understand the crisis of unaccompanied minors and its underlying causes, one must separate the facts from misinformation.

Where are Unaccompanied Minors Coming From?

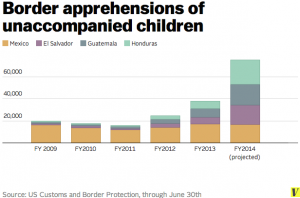

While the migration of unaccompanied minors to the U.S. has been occurring for decades, the stream of child migrants has been increasing since 2011 (Lind, 2014). One point of much confusion during this influx has been the country or region from which these children originate. The vast majority of unaccompanied minors who have migrated to the U.S. over the past several years have originated from three Central American countries; Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras (Tobia, 2014). On the surface, this may seem like a superficial detail. However, the country from which immigrants to the U.S. originates is intimately related to the motivations for migration (Rumbaut and Portes, 2001). The unaccompanied minors that have come in incredibly large numbers to the U.S. over the past few years are largely motivated by concerns regarding safety and security.

Why are Unaccompanied Minors Migrating?

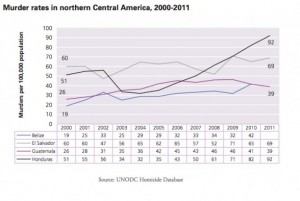

The three countries where most unaccompanied child migrants originate, Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, have some of the highest murder rates in the entire world (Tobia, 2014). This extreme violence is fueled by gangs and drug cartels, who target children for recruitment at very young ages (Resnick, 2014). Unaccompanied child migrants regularly cite instances of extreme violence in their home countries as the primary reason for their exodus. A report by the U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees (2014) found that 58% of a sample of unaccompanied migrants were forcibly displaced by violence and potentially qualified for international protection. The acts of violence directed towards children are largely utilized as a means of intimidation, forcing children into working for the gangs and cartels. Rape, murder, and dismemberment are all used as tools for recruitment, forcing children to choose between a brutal death at the hands of the gangs or the high risk of death by the police as a member of the cartel (Voorhees, 2014). Faced with this impossible decision, many children make the difficult decision to migrate in the hopes of a more secure future.

Aside from the flight from violence, there are a number of reasons child migrants make their unaccompanied journeys to the United States. Unaccompanied child migrants express hope for educational and occupational opportunity, and for reunification with family who have already migrated to America (U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees, 2014). However, for the surge of child migrants between 2011 and 2014, these hopes are less urgent than their intentions to escape gang violence.

To where are the Unaccompanied Minors Migrating?

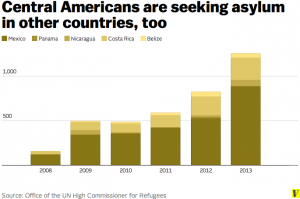

The U.S. is not the only country experiencing an increase in unaccompanied child migrants. Source: Lind, 2014

One of the great fallacies of the discussion surrounding the crisis of unaccompanied child migrants during the summer of 2014 was the erroneous assumption that U.S. was the only destination for these minors. If unaccompanied children were migrating specifically to the U.S., it would logically follow that there must be some factor or factors attracting children to the U.S., in addition to the factors pushing them away from their home countries. This assumption was central to the arguments made by many conservative politicians and pundits, who contended that the lax enforcement of immigration laws by the Obama administration, from deferred action policies to border security, have enticed child migrants to make the dangerous trek on their own (Tobia, 2014). In reality, unaccompanied child migrants from Central America are seeking asylum in nations throughout the region (Lind, 2014). If, as conservatives have argued, child migrants are drawn to America due to the Obama administration’s severely broken immigration policies, we would not expect to see other countries experiencing a similar surge in unaccompanied child migrants. Their argument if further discredited by the U.N. survey data from a sample of Central American child migrants, in which only 2% of the unaccompanied minors mentioned anything about U.S. immigration policy (Resnick, 2014). Finally, it is important to note that, contrary to conservatives’ contentions, the Obama administration’s immigration policy has included unprecedented numbers of deportations and a drastic increase in spending on border security (Washington Office on Latin America, 2014).

What happens to Unaccompanied Child Migrants after their Arrival in the U.S.?

Detention facilities for unaccompanied child migrants often lack the educational, healthcare, and legal resources these children require. Source: Tobia, 2014

For several decades, the detention centers that house unaccompanied child migrants awaiting deportation or asylum hearings from the U.S. have had a history of inhumane conditions, severely lacking the educational, healthcare, and legal resources so desperately needed by these children (Navarro, 1998). The scarce availability of legal counsel is particularly devastating for these vulnerable groups of children, as it is virtually impossible for an unaccompanied child with limited English language proficiency to navigate the complexities of U.S. immigration law. Unaccompanied minors may be eligible for Special Immigrant Juvenile (SIJ) status, a form of legal residency granted to a child migrants who can prove he or she is a victim of neglect, abuse, or abandonment, or that deportation to their home country would be significantly detrimental to the child’s best interest (Lloyd, 2005). However, because of the law’s ambiguity, it can be incredibly difficult to establish neglect, abuse, or abandonment, or what constitutes a significant breach in the child’s best interest. For these reasons, SIJ status is difficult to attain. Finally, researchers have found that the deportation of undocumented immigrants with familial ties in America can lead to a circular migration, in which the migrants will attempt to return to America (Hagan, Eschbach, and Rodriguez 2008). It is not difficult to imagine that unaccompanied minors with family in the U.S., or children who were compelled to migrate due to excessive levels of violence in their home countries, could attempt to migrate again. Until the root causes for unaccompanied migration are ameliorated, most prominently the extreme levels of violence experienced in Central American countries fueled by gangs and drug cartels, child migrants will continue to make the unaccompanied journey to secure their personal safety.

References

Hagan, Jacqueline, Karl Eschbach, and Nestor Rodriguez. 2008. “U.S. Deportation Policy, Family Separation, and Circular Migration.” International Migration Review 42(1):64-88.

Lind, Dara. 2014. “14 facts that help explain America’s child migrant crisis” Vox, July 29. Retrieved December 15, 2014 (http://www.vox.com/2014/6/16/5813406/explain-child-migrant-crisis-central-america-unaccompanied-children-immigrants-daca)

Lloyd, Angela. 2005. “Regulating Consent: Protecting Undocumented Immigrant Children from their (Evil) Step-Uncle Sam, or How to Ameliorate the Impact of the 1997 Amendments to the SIJ law.” Public Interest Law Journal 15:237-261.

Navarro, Lisa Rodriquez. 1998. “An Analysis of Treatment of Unaccompanied Immigrant and Refugee Children in INS Detention and Other Forms of Institutionalized Custody.” Chicano-Latino Law Review 19:589-612.

Resnick, Brian. 2014. “Why 90,000 Children Flooding Our Border Is Not an Immigration Story”. National Journal, June 16. Retrieved December 15, 2014 (http://www.nationaljournal.com/domesticpolicy/why-90-000-children-flooding-our-border-is-not-an-immigration-story-20140616)

Rumbaut, Ruben and Alejandro Portes, eds. 2001. Ethnicities: Children of immigrants in America. University of California Press.

Tobia, P. J. 2014. “No country for lost kids” PBS Newshour, June 20. Retrieved December 15, 2014 (http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/country-lost-kids/)

U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees. 2014. Children on the Run. Washington, D.C. Retrieved December 15, 2014 (http://www.unhcrwashington.org).

Voorhees, Josh. 2014. “What Immigration Crisis?” Slate, August 20. Retrieved December 15, 2014 (http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/politics/2014/08/child_migrant_crisis_the_number_of_unaccompanied_minors_being_arrest_has.html)

Washington Office on Latin America. 2014. “Three Myths about Central American Migration to the United States” June 17. Retrieved December 15, 2014 (http://www.wola.org/commentary/3_myths_about_central_american_migration_to_the_us)