Qijiaping

May 10, 2017

Alternate Spellings: Qi Jiaping, Ch’i-Chia

Chinese: 齊家坪

Location:

35º29’48.40” N 103º49’58.44” E (Google Earth)

Elevation:

6363 ft

Qijiaping is a Late Neolithic site located just outside of Qijiaping Village in Guanghe, Gansu, China, about 35 miles east of the Linxia Hui Autonomous District. At an elevation of around 6,000 ft, Qijiaping is nestled between the Tibetan and Loess plateaus on a terrace above the Taohe River, as well as roughly 300 miles east of the Yellow River (Zhimin, 1992). Qijiaping site covers an area of 1.5km² and neighbors a number of surrounding cities and villages such as Paizipingcun, Shijiatan and Dongping.

The Qijiaping site was first discovered and excavated by Swedish geologist and archaeologist Johan Gunnar Andersson in 1924. Andersson’s initial excavation not only revealed numerous graves and preserved artifacts, but was simultaneously the discovery of an entire culture. Qijia Culture, named after it’s respective locale, is the only known Neolithic culture in China that shows northern Eurasian influence (Xia, 2008). Qijia culture is centered by the archaeological site at Qijiaping, but spans further, reaching as close as the upper Taohe, Daxia and Weihe rivers in the Gansu Province and as far as the Huangshi Basin in the upper reaches of the Yellow River in Qinghai (Zhimin, 1992). Additional site discoveries and excavations, like those of Chinese archaeologists Pei Wenzhong and Xia Nai in the neighboring villages of Yangwawan and Cuijiazhuang in the 1940s and 50s, spearheaded the conceptualization of Qijia culture. Their discoveries, among others, concluded that Qijiaping was not unique, but rather the piece of a larger puzzle.

(Map of Qijiaping (4) and other Qijia culture sites like Dadiwan (1), Zongri (2), Lajia (3), Shangsunajia (5)) (Ma, Dong et al. 2013)

Qijiaping and Qijia culture have been dated back to c. 2200 – 1900 BCE via radiocarbon analysis and subsequently discerned to be a transitional period between the end of the Neolithic Age and the beginning of the Bronze Age (de Laet, Dani 1994). This transcendence of era is directly manifested in retrieved artifacts from the site(s). In a 1975 excavation of Qijiaping, dozens of artifacts were unearthed, ranging from stone tools and clay pottery to bronze mirrors.

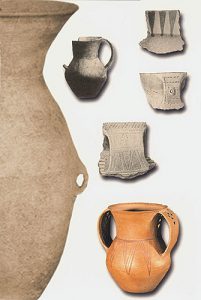

Qijia pottery however is nothing ordinary. In fact, it is some of the best evidence of transcultural influence and trans-Eurasian contact to date. Qijia pottery was crafted by hand with fine red ware and a coarse reddish-brown ware, a commonplace resource of China. What is markedly different about Qijia pottery however is its design. While it has its own stylistic characteristics, Qijia pottery is often found with comblike designs and amphora-like vases, both of which were presumably alien to China. Anthropologists suggest this to be evidence of cultural contact and trade across Eurasia.

(Potter urn: container (left-up, height 11.8 cm); Painted pottery fragment with triangle design: (right-up, height 4.7 cm); Pottery fragment from the ear of vessel: (up of the right-mid, height 4 cm); Pottery fragment from the ear of vessel: (bottom of the right-mid, height 4.8 cm); Painted pottery amphora with the pattern of triangle: food container (height 10.2 cm)) (Chen 2013)

The bronze mirror found in the 1975 excavation of Qijiaping serves a similar purpose. The discovery of the mirror dismantles all presumptions of cultural development in the Gansu Province – it suggests that early Chinese bronze casting may have originated in Western China, and may even have lineage to bronze casting in Central Asia and the Iranian area, suggesting, like the pottery, the existence of trans-Eurasian exchange (Chen, Mao, et al. 2012).

(Bronze mirror, Gansu. Qijia culture (2400 – 1900) National Museum of China)

Stone and bone tools were also found at the site, keeping the conception of Qijia culture in the Neolithic Age.

In addition to tools, pottery and bronze mirrors, the 1975 excavation of Qijiaping yielded hundreds of animal and human bone remains, shedding light on lifestyle, tradition and even diet. The discoveries reveal a sedentary lifestyle based on agriculture. Pig, sheep, goat and cow remains suggest domestication. Furthermore, large quantities of millet have also been found and is surprisingly the impetus behind the search for evidence of trans-Eurasian trade. Human bones from Qijiaping were isotopically analyzed to study the diet patterns of the Qijia people and unexpectedly revealed the existence of not only millet in the diet, but wheat and barley as well. The presence of wheat and barley in Qijia diet is crucial because at the time, wheat and barley only really existed in the west. Therefore to be included in their diet, the Qijia people must have had contact and trade with western civilizations (Ma, Dong, et al. 2013).

Qijiaping and its neighboring Qijia sites have also produced over 800 burial sites since discovery in 1924. These burial sites, organized in cemeteries of various size, express social sophistication and potential hierarchical tradition in Qijia culture. For example, while many burials are singular, it is not uncommon to find a man and woman buried together. Moreover, there are even cases in which two flexed women are buried on either side of a deceased man, indicating the inferiority of women and their subjugation to men in Qijia culture. Furthermore, grave goods vary greatly across Qijia sites, suggesting some form of social hierarchy. For example, at the Huangniangniangtai cemetery in Wuwei County, Gansu Province, men are buried with up to 37 pieces of pottery. At the Qinweijia cemetery in Yongjing County, Gansu Province, men are buried with up to 68 pieces of pigs’ mandibles. Anthropologists believe this to be evidence of social hierarchy in Qijia culture (de Laet, Dani 1994).

Qijiaping is one of the most imperative archaeological sites in ancient western China. The discovery of Qijiaping in 1924 not only unearthed artifacts but an entire lost culture. Qijiaping has drawn attention to a seemingly stagnant area. It has become one of the most pertinent archaeological sites in China today and has shaped the ways in which anthropologists understand prehistory in Eurasia. Qijiaping has enlightened the anthropological community to trans-Eurasian trade and has opened new doors to understanding how the west and the east are more connected than previously presumed.

Works Cited

Chen, Honghai. “The Qijia culture in the upper Yellow River valley.” A Companion to Chinese Archaeology. Blackwell. pp 105-124. 2013.

Chen, Jianli, Mao, Ruilin, Wang, Hui, Chen, Honghai, Xie, Yan, Qian, Yaopeng. The iron objects unearthed from tombs of the Siwa culture in Mogou, Gansu, and the origin of iron-making technology in China. Wenwu (Cult. Relics) 8,45-53. 2012. (in Chinese)

de Laet, Sigfried J., Dani, Ahmad Hasan. History of Humanity: From the third millennium to the seventh century B.C. UNESCO, 1994.

Ma, M., Dong, G., Liu, X., Lightfoot, E., Chen, F., Wang, H., Li, H., Jones, M. K. Stable Isotope Analysis of Human and Animal Remains at the Qijiaping Site in Middle Gansu, China. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 13 Dec, 2013.

Xia, Zhihou. Chinese History: Qijia Culture. Encyclopedia Britannica. 5 Sep, 2008.

Zhimin, An. “The Bronze Age in eastern parts of Central Asia.” History of Civilizations of Central Asia, volume 1: The Dawn of Civilization: Earliest Times to 700 B.C. UNESCO. pp. 308 – 325. 1992.