The Subeixi Site (& Cemeteries)

May 9, 2017

Also Known As: Su Beixi / 苏贝希 (Chinese – “Suibei”)

(Closest) Coordinates: 42.858519 N, 89.691976 E

Most commonly known in its scholarship as “The Subeixi Site,” this site shares its named both with the nearby village of Subeixi (meaning “origin of water,” as the village lies in a small oasis north of Mt. Huoyan) as well as with what its referred to as the “Subeixi culture,” believe to have occupied areas in the Turpan Basin nearly 3,000 years ago (Lu & Zheng, 2003; Hirst , 2016). Though located in the Turpan Basin, Shanshan County, Xinjiang Uighur (/Uyghur) Autonomous Region of China, there is some ambiguity in texts referring to work done at the site regarding its precise location, as some merely say it lies within the Tuyugou Valley (Gong et al., 2011). With many of the accounts not providing a set of coordinates by which to easily locate the site, the description which Lu & Zheng give is:

“The site lies in the center of the Mt. Huoyan, 3 km south of the Subeixi Village. It is on an irregular terrace, which likes an isolated island, surrounded by cliffs. The terrace’s east side is lower than the west side, with uneven surface.” (Lu & Zheng, 2003)

[With several accounts saying the Subeixi site lies within the Tuyugou Valley and and/or is under the control of Tuyugou Township, Shanshan County, the closest image capable on Google Earth is of the whole Tuyugou Valley. The site is cited as being somewhere north of the valley, on the eastern-facing side of the Flaming Mountains/Mt. Huoyan. The distance from the Tuyugou Valley to the town of Shanshan is measured as approximately 42.47 km. ]

Site location map from Jiang et al. (2006) provided in several articles, yet no definitive coordinates have been cited.

The site itself contains the remains of three houses and three cemeteries, holding several large deposits of artifacts both in surface findings as well as when excavations were performed. Radiocarbon dating of items found both in the house remains and from the coffin beds within the cemetery graves dates the overall site between 500-300 BCE, further confirmed by dating performed on several of the unearthed artifacts (Lu & Zheng, 2003). Though involving so many different individual sites, the houses and cemeteries were grouped together under the label of “Subeixi site” as per not only similarities found between different items but also as there were no other large sites of such items found in the nearby vicinity (Gong et al., 2011). Excavations performed at the site began in May 1980 (focusing on the house remains and cemeteries No. 1 & 2) and continued with the discovery of cemetery No. 3 in 1992 during major highway construction, most of which were headed by Professor Enguo Lu of the Xinjiang Institute of Archaeology, in cooperation with other institutions.

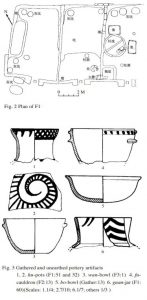

The three house remains covered an area of 400 m² and included items like scattered stone artifacts, woolen textile fragments, pottery shards, and adobe wall foundations (Lu & Zheng, 2003). The first house (F1) is described as rectangular in shape (13.6 m x 8.1 m), consisting of three separate rooms with the west most room containing an oblong trough, leading it to be interpreted as a room for food storage (with bits of straw and shells of broomcorn millet being found). The middle room contains a hearth-like structure, and the east room includes many differently shaped tanks and pits, causing researchers to believe it served as a pottery workshop. Much of items unearthed were millstones (grindstones), stone pestles, and potshards, with the potshards showing a variety of pottery types including fu-cauldrons, guan-jars, bo-bowls, wan-bowls, hu-pots, and lamps (Lu & Zheng, 2003). The other 2 housing remains are described as “badly preserved,” with very few artifacts being recovered and those that were being of very poor quality (Gong et al., 2011).

Layout of house F1, alongside images of unearthed artifacts showing the house’s use for crafting pottery.

Perhaps the more sensationalized parts of the Subeixi site are the cemetery artifacts that have been recovered, specifically those of human remains. Spread across three different labeled cemeteries (No. 1, 2, & 3), a total of 19 sets of mummified remains have been catalogued and recovered (13 identified as Caucasian, 3 as Mongolian/Mongoloid, and 3 as being of mixed race/ethnicity), with associated artifacts/grave goods appearing like those found in the house remains (Shevchenko et al., 2013). Cemetery No. 1, located 600 m north of the site, covers over 3000 m² and is split into two sections, with the east section containing 20 burials (8 of which were excavated in 1980, labeled M1-M8) and the west section containing 32 burials (5 excavated in 1980, labeled M9-M13) (Lu & Zheng, 2003). Of the western section excavations, consisting of 4 earth-pit and 1 cave-cum-shaft burials, held unearthed items of pottery, stone, iron, bronze, leather, and other woolen artifacts, with the human remains of one burial (M11) including a woman, man, and infant (Image below). Cemetery No. 3, located on a terrace 80 m west of the site (Area of 80 m x 20 m), was excavated in 1992, unearthing 30 burials and similar funerary objects like ceramic vessels (some containing food remains), wooden wares, ironware, stone tools, bone artifacts, and woolen/leather articles (Gong et al., 2011).

Complete set of mummified female remains found in labeled grave M11 at Cemetery No. 1 site.

Several recent examinations of this site have turned to food remains found within the cemetery grave goods, looking to reveal potential ancient food preparation techniques in the hopes of revealing similarities in these to other groups moving near/through this area at the time (Gong et al, 2011; Shevchenko et al., 2013; Hong et al., 2012). Utilizing methods involving proteomic examinations of food residue/remains such as sourdough bread (Svechenko et al., 2013) and milk components (Hong et al., 2012) as well as performing simulated cooking methods of cakes, millet, and noodles (Gong et al., 2011) found mostly within grave goods, the researchers present similar hypotheses that these preparatory procedures further indicate the Subeixi site as an integral part of eastern and western societal/group communication. With the Turpan basin constructed with the role of route for cultural communication, as well as with work done at other nearby sites like the Astana cemeteries and its evidence of Cannabis fiber being utilized in ancient burial practices (Chen et al., 2014), it may be possible to see that the East/West divide of Eurasia might have been closer than previously thought.

References

Chen, Tao, Shuwen Yao, Mark Merlin, Huijuan Mai, Zhenwei Qiu, Yaowu Hu, Bo Wang, Changsui Wang, and Hongen Jiang. 2014. “Identification of Cannabis Fiber from the Astana Cemeteries, Xinjiang, China, with Reference to Its Unique Decorative Utilization.” Economic Botany 68 (1): 59-66. Bronx, NY: The New York Botanical Garden Press.

Gong, Yiwen, Yimin Yang, David K. Ferguson, Dawei Tao, Wenying Li, Changsui Wang, Enguo Lu, and Hongen Jiang. 2011. “Investigation of ancient noodles, cakes, and millet at the Subeixi Site, Xinjiang, China.” Journal of Archaeological Science 38: 470-479. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2010.10.006.

Hirst, K. Kris. 2016. “The Gushi Kingdom – Archaeology of the Subeixi Culture in Turpan: The First Permanent Residents of the Turpan Basin in China.” ThoughtCo., October 16. Accessed May 9, 2017. https://www.thoughtco.com/gushi-kingdom-subeixi-culture-in-turpan-169398.

Hong, Chuan, Hongen Jiang, Enguo Lu, Yunfei Wu, Lihai Guo, Yongming Xie, Changsui Wang, and Yimin Yang. 2012. “Identification of Milk Component in Ancient Food Residue by Proteomics.” PLoS ONE 7(5). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037053.

Lu, Enguo, and Boqiu Zheng. 2003. “The Subeixi Site and Cemeteries in Shanshan County, Xinjiang.” Translated by Yi Nan. Chinese Archaeology 3: 135-142.

Shevchenko, Anna, Yimin Yang, Andrea Knaust, Henrik Thomas, Hongen Jiang, Enguo Lu, Changsui Wang, and Andrej Shevchenko. 2013. “Proteomics identifies the composition and manufacturing recipe of the 2500-year old sourdough bread from Subeixi cemetery in China.” Journal of Proteomics 105: 363-371. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2013.11.016.