The Peahen Who Cried Wolf: Peafowl Can Differentiate Between the Anti-predator Calls of Conspecifics

Male Peahen (Pavo cristatus) https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/bb/Pavo_cristatus_-Castellar_Zoo,_Castellar_de_la_Frontera,_Spain-8a.png

When it comes to being able to differentiate between the calls of comrades when a predator is near, it certainly pays to recognize their individual vocalizations. Your tail feathers have a better chance of being spared if you can distinguish a truthful alarm call from a non-truthful one, especially if that alarm call is being produced by multiple individuals at the same time. Peahens (Pavo cristatus), or more commonly referred to as peacocks, have been found to do precisely that. When a predator is detected, peahens produce an anti-predator call in the form of a ‘bu-girk’ vocalization. This call has been found to contain a sufficient amount of acoustic variation among individuals to allow for individual recognition. And because peafowl tend to congregate in large groups, it makes sense to hypothesize that they should be able to discriminate among the anti-predator calls of their comrades. However, little research has been conducted on avian species and their ability to recognize and respond to anti-predator calls.

Mark Nichols and Jessica Yorzinski recently released their research conducted among peahens, in which they examined whether the birds are able to differentiate between the anti-predator calls of individual conspecifics based on the acoustic features of the caller’s vocalizations (Nichols & Yorzinski, 2016). For their experiment the authors used a habituation-discrimination playback paradigm, which involved first habituating the peahens to the anti-predator calls of a selected individual (individual A) and then examining their responses to additional calls from that same individual, as well as to calls from a novel individual (individual B). They hypothesized that if the peahen being habituated (i.e. the focal peahen) is able to differentiate among the individual callers, then it should respond more strongly to the anti-predator calls from the novel individual (individual B) compared to the first individual (individual A).

To test their hypothesis, Nichols and Yorzinski created a habituation playback loop of the peahens’ anti-predator vocalizations (60 calls total), along with two stimulus sets: 1) using five randomly selected calls from Individual A (different from those used in the habituation loop), and 2) using five randomly selected calls from a different peahen (Individual B). For each trial (32 in total), a single female peahen was habituated in an indoor enclosure and then presented with the habituation and stimulus sets playback loops via a large speaker positioned outside of the enclosure that pointed directly at the peahen’s perch. Two cameras were used to record the responses of each of the bird’s eyes (since peahen asymmetrically close their eyes during sleep), with a response defined as the bird opening either of its eyes within two seconds of the call’s end.

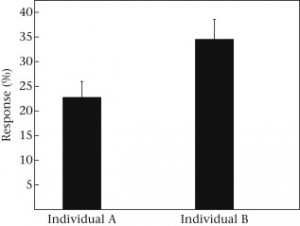

Figure 1.

Responses (%) of peahens to stimulus calls produced by the individual that called during the habituation loops (‘individual A’) and to calls produced by a novel individual (‘individual B’). Means ± SE are displayed.

From their study, the researchers found that, when habituated to the anti-predator calls of one individual, the peahens responded less frequently to different calls from that individual compared to calls from a novel individual (Figure 1). This finding is in agreement with their hypothesis and it strongly suggests that peahens can, in fact, differentiate between the anti-predator calls of their conspecifics.

While many studies similar to this one have found a difference in response to anti-predator calls of other species, this is among the first to look specifically at avian species and whether they, too, are capable of discriminating between such calls. These findings are important for understanding the cooperation of birds as a social species, how they communicate, and how their vocalizations have evolved and continue to evolve. The ability of peahens to differentiate between individual callers may be useful to them in modifying their anti-predator behavior based on signaler reliability, which translates to an increased survival rate. As the saying goes, birds of a feather flock together… And warn each other of predators.

Reference:

Nichols, M. R. & Yorzinski, J. L. (2016). Peahens can differentiate between the antipredator calls of individual conspecifics. Animal Behaviour, 112: 23-27.