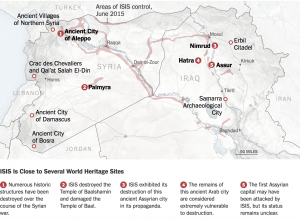

While notorious for public beheadings, ISIS also attacks Syrian and Iraqi artifacts and ancient sites. ISIS follows a strict Salafi interpretation of Islam that prohibits worship of shrines, tombs, and idols, and this interpretation leads ISIS to destroy churches, mosques, and even artifacts and antiquities deemed idolatrous. In 2015, ISIS territories were situated next to several world heritage sites (Figure 1), many of which they destroyed. Irina Bokova, the head of the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization, refers to the destruction of antiques as “cultural cleansing”, and says that destroying artifacts “adds to the systematic destruction of heritage and the persecution of minorities that seeks to wipe out the cultural diversity that is the soul of the Iraqi people” (Hartmann 2015).

ISIS employs the brutal war tactic of publically destroying the culture of those who disagree with their ideals, including posting a photo showcasing the destruction of a religious site (Figure 2). ISIS is attempting to erase history. They are symbolically trying to disconnect their enemies from the past and the land, and they are trying to pave the way for a future in which the only history of Syria and Iraq is the history of ISIS.

ISIS’ attacks are demoralizing, horrific, and profitable. Selling and looting antiquities is ISIS’ second highest source of funding after oil, making the destruction of culture both a profitable escapade and a form of cultural warfare. In light of this news, in 2014 the U.S. sought to implement a bipartisan cultural protection czar to reduce the amount of smuggled antiques into the U.S. in order to curtail ISIS funding (Muñoz-Alonso 2014). Both the U.S. and Germany have started imposing laws that would catch smuggled artifacts at their respective borders.

In recent years, ISIS has lost 96% of its territories (Bendaoudi 2018). Still, the sites and antiques ISIS destroyed can never be truly rebuilt, which is why the impact of cultural warfare is so tragic. If the past is forgotten, those in the future can never look back to where they came from, and the connection to the land, the culture, and the people of the past could be lost. Governments and the UN must defend antiques and world historical sites from terror, and their importance must never be forgotten. For this reason, archaeology and the study of the past remain relevant and important subjects today.

Figure 1. ISIS territories in proximity to world heritage sites. Graphic by New York Times. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Nimrud is on the Tentative World Heritage List); Institute for the Study of War (control areas); Satellite image by Landsat via Google Earth

Works Cited:

Muñoz-Alonso, Lorena

2014 Could US Cultural Protection Czar Stop Rampant ISIS Looting? Electronic document, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/could-us-cultural-protection-czar-stop-rampant-isis-looting-173972, accessed November 9, 2018.

Hartmann, Margaret

2015 ISIS is Destroying Ancient Art in Iraq and Syria. Electronic document, http://nymag.com/intelligencer/2015/03/isis-destroys-ancient-art.html, accessed November 9, 2018.

Bendaoudi , Abdelillah

2018 After the “almost 100 percent” Defeat of ISIS, What about its Ideology? Electronic document, http://studies.aljazeera.net/en/reports/2018/05/100-percent-defeat-isis-ideology-180508042421376.html, accessed November 9, 2018.

Additional Content:

“How Antiques Have Been Weaponized in the Struggle to Preserve Culture”

How Antiquities Have Been Weaponized in the Struggle to Preserve Culture

“The Race to Save Syria’s Archaeological Treasures”

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/race-save-syrias-archaeological-treasures-180958097/