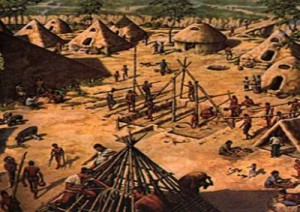

Since the very advent of agriculture, there has been warfare. Before agriculture, humans generally travelled in small, hunter-gatherer groups. Land ownership was not an important concept to these early hunter-gatherers as they were nomadic and did not need land for building or growing crops. Once agriculture emerged, land and resources suddenly became quite valuable. Fertile land was necessary for efficiently growing crops and so conflict arose over who had rights to certain areas. Furthermore, agriculture is more unreliable than hunting and gathering. Crops would often fail and groups with no food would raid those who did have food. Thus, war was born.

Understanding the causes of conflict can greatly help to mitigate the effects of war on today’s societies. Therefore, many archeologists are interested in creating an accurate model of what prehistoric warfare was like. One of the primary ways to do this is by trying to ascertain how many people died in specific prehistoric conflicts to see how large of an impact they had on the communities involved. To piece together a story, archeologists rely primarily on projectile points and other weapons that have not decomposed as well as skeletons with evidence of injury from these weapons. Unhealed fractures, shallow cuts around the skull indicating scalping, and projectile points imbedded in bone are a few of the more common indicators that war took place in a specific area. However, interpreting this evidence is a difficult and complicated endeavor.

Many factors must be taken into account when attempting to understand the effects of a war. For example, one must determine the lethality of the weapons used (what percentage of people survived being wounded) as well as the gender and age ratio and total population of the groups involved. Through statistics like these, archeologists can see how war affects entire communities and even surrounding communities that were not directly involved. To find the lethality of a weapon, archeologists will often recreate the weapon to test its accuracy and power. The medical knowledge of the prehistoric communities must also be taken into account. For instance, knowledge on how to treat arrow wounds was limited during the French-Indian war, so one can look at reports of the percentage of soldiers who died from arrow wounds then and extrapolate that a similar percentage would have died in a prehistoric war. Of course, with only skeletons to work with this provides only a loose estimate. Not all arrows struck bone and thus many who died from arrow wounds have no discernable marks on their skeletons to suggest that they were hit. Determining the effect on the overall community is equally difficult. The percentage of the total population killed must be estimated, as well as less tangible variables such as malnourishment or disease caused by war. Finally, and most importantly, archeologists observe how warfare has changed or destroyed cultures over time. By understanding this entire picture, we can predict the consequences of wars today and make informed decisions to minimize loss and tragedy.

Resources:

Sabloff, Jeremy A. Archaeology Matters: Action Archaeology in the Modern World.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/40035273?seq=9

http://culture-of-peace.info/books/history/prehistory-war.html

Image Links:

http://www.waldeneffect.org/blog/Agriculture:_Boon_or_bane__63__/

http://www.corbisimages.com/stock-photo/rights-managed/WF003567/skull-of-anasazi-woman-with-embedded-arrowhead