Last Tuesday, Professor Carlo Severi gave a lecture regarding a cult of Christianity (the Penitente Brotherhood) that developed in certain areas of the United States (New Mexico and Colorado). Since the Penitentes are a rather secretive group, Severi had to draw information on them from images and the conditions from which they arose. At the heart of his talk, he wanted to convey the necessity of the images and traditions developed within a culture. It was not enough that the images he presented merely be observed as empirically demonstrable facts; rather, he sought to show that the conditions of the culture in which they arose were such that they had to.

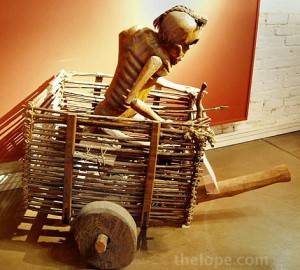

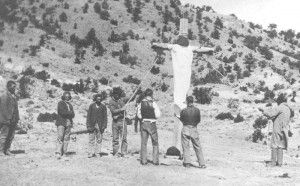

One of the major factors leading to its creation was the interaction of Christian civilizations with Native Americans. The lecturer noted their relationship was often contentious, resulting in fighting and killing. One particular image – that of a Native American attacking an image of Jesus – became particularly salient. The violence and persistence associated with these attacks were given a central role in cultic practice, to the point that a new saint, Dona Sebastiana, was created. This unique figure is always depicted as a skeletal woman, often wielding a bow and arrow. Even more interesting is the ritual associated with her in which an effigy of her with bow and arrow in posed to fire arrows at actual members of the cult who represent Jesus.

Beyond these visual differences, Severi went on to mention for theological differences between the Penitente Brotherhood and more mainstream Catholicism. All of the images he provided during his lecture were very morbid in nature. Dona Sebastiana for one was obviously a reminder of mortality, but beyond her, the Penitente Brotherhood practiced self-flagellation and simulated crucifixion. One image that stuck with me in particular was that of the flagellation of Christ. While this was by no means an unusual theme in Catholic imagery in general, the Penitente’s version was particularly graphic, the back of Christ being so abused as to reveal His spine and ribcage. This paired with the symbolic attack on Christ by Dona Sebastiana mentioned above constitute a view of Christianity in which death seems to triumph over Christ rather than the other way around.

With this in mind, I felt Severi’s argument for the images necessity to be compelling. Given the social climate in which attacks from Native Americas were a frightening threat and the relationship Catholic theology already had with death, the incorporation of new death images and attitudes seems at least a natural progression, if not a necessary one.

Images

http://cdn2.brooklynmuseum.org/images/opencollection/objects/size3/1997.70_transp5516.jpg

Weigle, Marta. “Ghostly Flagellants and Doña Sebastiana: Two Legends of the Penitente Brotherhood”. Western Folklore , Vol. 36, No. 2 (Apr., 1977), p 136

Further Reading

Weigle, Marta. “Ghostly Flagellants and Doña Sebastiana: Two Legends of the Penitente Brotherhood”. Western Folklore , Vol. 36, No. 2 (Apr., 1977), p 135-147