Archaeological discoveries in Bolivian savannas reveal how Pre-Columbian societies used aquaculture, or fish farming, as a method of adaptation. The Llanos de Moxos region, which lies on the outskirts of the Amazon rainforest, is characterized by expansive grasslands and months of torrential floods and subsequent drought.

The remains of canals, mounds, and other features suggest that societies permanently inhabited the austere landscape. Despite this overwhelming evidence, the Llanos de Moxos lied at the center of a decades-long dispute within archaeology. The prominent archaeologist Betty Meggers asserted that the region was incompatible with long-term settlements due to poor soil conditions and massive flooding (Mann 2000). Similarly, researchers associated the Smithsonian Institute took issue with the earthworks themselves, claiming that such features are the result of natural processes or migratory bands of settlers (Mann 2000). The environmental destruction of artifacts in the plains also contributed to the poor understanding of the region. Unfortunately, this dismissal of the archaeological record constituted the overwhelming consensus.

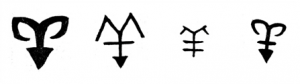

Intensive fieldwork only made possible by the easing of political tensions supports the existence of permanent, large-scale societies through the analysis of structures used for aquaculture. Inhabitants of the plains constructed lengthy walls with zigzags at various points. During periods of flooding, fish would swim through the channels and collect in traps, also referred to as fish weirs. (Figure 1). Archaeologists have also discovered extensive artificial ponds, most likely used for raising fish during the dry seasons (Mann 2000).

A recent excavation of the Loma Salvatierra mound provides greater insight on the extent of fish farming in the Llanos de Moxos region. The mound, which was occupied between 500 and 1400, is situated near a network of channels and ponds. A team of archaeologists discovered 17,338 fish remains in 62 stratigraphic units, most of which were remarkably well-preserved. While complete species identification of all the fish remains elusive, 63% were identified to the order level, representing a great diversity (Prestes-Carniero et al. 2019) (Figure 2). The three most common groups of fish raised at Loma Salvatierra include swamp eels, armored catfish, and lungfish. These species are well-suited to the dry conditions of the drought periods, suggesting that the mound was the center of a society that inhabited the plains year-round (Prestes-Carniero et al. 2019).

The findings at the Loma Salvatierra site significantly contribute to our understanding of how societies in the Llanos de Moxos adapted to the alternating cycles of flooding and drought. Furthermore, the contention surrounding the region illustrates conflicts within the discipline of archaeology; discoveries are often made that contradict previous assumptions about people and places studied.

References

Mann, Charles C.

2000 Earthmovers of the Amazon. Electronic Document,

https://www.sas.upenn.edu/~cerickso/baures/Mann2.html, accessed

September 29, 2019.

Further Reading

A brief history on aquaculture

https://www.alimentarium.org/en/knowledge/history-aquaculture

An introduction to the geography and climate of Bolivia’s Moxos plains

https://www.worldwildlife.org/ecoregions/nt0702