Though archaeologists can come up with good guesses about the date of artifacts through different processes, most methods of dating are trumped by a relatively new technique called radiocarbon dating. Developed in 1949, it is considered the most useful way of determining the dates of artifacts for archaeologists.

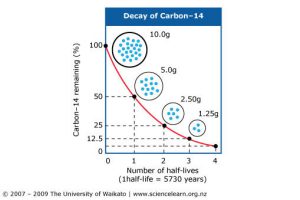

Radiocarbon dating was discovered when chemist Willard Libby realized radioactive carbon-14 (14C) is made in the Earth’s atmosphere, and then absorbed into plants and entered into the carbon cycle. Since 14C is radioactive, it decays at a relatively quick exponential rate (Figure 1), while non-radioactive carbon (12C) does not. By measuring an artifact’s 14C to 12C ratio, chemists can determine the date of any organic material that was part of the carbon cycle (Bahn and Renfrew 2010:210).

While Libby noted that radiocarbon dating remains effective because the amount of 14C produced in the atmosphere does not vary with time, this may not always be the case.

Fossil fuel emissions have undoubtedly raised the amount of 12C in the atmosphere, with there being an upward trend in in the metric tons of Carbon in the atmosphere since the industrial revolution (Figure 2). CO2 emissions have increased by 90% since 1970 (EPA 2017), and it is therefore important to consider the effects of this new carbon in the atmosphere on radiocarbon dating, the effectiveness of which remains contingent upon the fact that the proportion of 14C in the atmosphere does not vary.

When fossil fuels are released into the atmosphere, they release 12C, and not 14C. This changes the ratio of 12C to 14C, which is what is measured to date artifacts. If the excess C12 in the atmosphere brought about by global warming enters the carbon cycle, the ratio of 12C to 14C increases greatly, making new organic material read as much older (Graven, Heather D. 2015). With an excess of 12C in the atmosphere, new organic materials will have the same 14C : 12C ratio as organic material from 1050.

If humans continue to release carbon into the atmosphere, many methods of radiocarbon dating will no longer be viable, and will not be able to provide absolute dates for artifacts up to 2,000 years old (Graven, Heather D. 2015).

Though there are other methods of dating, radiocarbon is favored, and many methods must be used in tandem to provide the most accurate dates possible (Bahn and Renfrew 2010).

Dating as we know it will change if the carbon being released into the atmosphere cannot be managed.

Figure 2. Million Metric Tons of Carbon in the atmosphere vs. year. Graph by Boden, T.A., G. Marland, and R.J. Andres 2017

Works Cited:

Bahn, Paul and Colin Renfrew

2010 Archaeology Essentials. 2nd Edition Thames & Hudson Inc., New York, NY.

United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

2017 Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data. Electronic document, https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-data, accessed September 22nd, 2018

Graven, Heather D.

2015 Impact of fossil fuel emissions on atmospheric radiocarbon and various applications of radiocarbon over this century. Electronic document, http://www.pnas.org/content/112/31/9542, accessed September 22nd, 2018

Additional Content:

“The Future of Radiocarbon Dating”

“How Carbon-14 Dating Works”

https://science.howstuffworks.com/environmental/earth/geology/carbon-14.htm

/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/new_tattoo_631.jpg)