American anthropologist Paul Farmer defines structural violence as “violence exerted systemically—that is, indirectly—by everyone who belongs to a certain social order: hence the discomfort these ideas provoke in a moral economy still geared to pinning praise or blame on individual actors” (Farmer). Where do we see instances of structural violence take shape in the past, as well as in the present day?

Fans of the popular post-apocalyptic zombie thriller The Walking Dead will recall the scene where Morgan, a significant character in the series, is trapped inside a prison cell in the cabin of a man he has just met. Days pass yet continues to Morgan remain in the cell. Eventually, his benevolent captor reveals that the cell door has been unlocked the whole time and that Morgan could have escaped at a moment’s notice. Why then did Morgan stay?

This scene in popular media illustrates the phenomenon of structural or institutionalized violence. Near Eastern archaeologist Susan Pollock argues that “we experience structures as pre-existing entities, as external objectivities that oppress us by their weight, making us suffer” (Pollock). In this specific situation, Morgan suffers from the environment around him: a world littered with disorder, hostility, and inhumanity. Furthermore, the “pre-existing entity” of the prison cell that contains Morgan overcomes any sense of freedom he might have felt prior to his captivity. Even though the cell door is just metal shaped to the will of humans, it bears a much more significant effect on its inhabitant. While Morgan is in actuality a free man, in the sense that he can walk out at any time, his familiarity with the connotation of a prison cell convinces himself that he is a prisoner.

Structural violence embodied in reality is evident in the case of Nazi Germany. Hitler and his Nazis created a society whose structure oppressed others via government, culture, labor, terror, and propaganda. Most reminiscent of this violence were the Nazi concentration camps. These camps imprisoned “enemies” of the Nazi party, peoples whose very existence were threatened Nazi ideology. Recovered artifacts and features of the site reveal that inmates suffered harsh living conditions and were subjected to forced labor; as a result, several didn’t make out of these camps alive (USHMM). Thus, Nazi Germany committed structural violence through its imposition of the system of concentration camps upon wrongfully accused peoples.

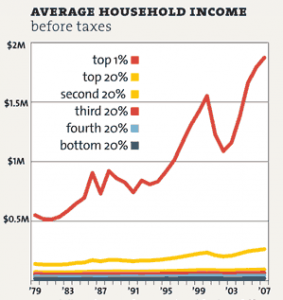

What implications does structural violence carry in today’s society? Farmer also states “As the twentieth century draws to a close, the world’s poor are the chief victims of structural violence—a violence which has thus far defied the nature and distribution of extreme suffering. Why might this be so? One answer is that the poor are not only more likely to suffer; they are also more likely to have their suffering silenced” (Farmer). Today’s social order allows for the growing trend of the rich becoming richer and the poor becoming poorer. Therefore, poverty caused by the system is, in itself, a form of inflicting structural violence.

Sources:

- Farmer, Paul. “An Anthropology of Structural Violence.” Current Anthropology Volume 45, Number 3. June 2004. Accessed November 17, 2017. http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdfplus/10.1086/382250

- Farmer, Paul. “On Suffering and Structural Violence: A View From Below.” Daedalus. 1996. Accessed November 18, 2017. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/20027362.pdf

- Pollock, Susan. “The Subject of Suffering.” American Anthropologist. November 15, 2016. Accessed November 18, 2017. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/aman.12686/full

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Concentration Camps, 1933-1939.” Holocaust Encyclopedia. Accessed November 18, 2017. https://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005263

- Walking Dead Wiki Contributors. “Morgan Jones (TV Series).” Walking Dead Wiki. November 16, 2017. Accessed November 17, 2017. http://walkingdead.wikia.com/wiki/Morgan_Jones_(TV_Series)

Image Sources:

- Morgan sits in the prison cell. Daily Mail. Accessed November 19, 2017. http://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-3299881/The-Walking-Dead-removes-actor-Steven-Yeun-credits-Glenn-Rhee-s-apparent-death-stand-episode-focuses-Morgan-s-story.html

- Average household income. Mother Jones. Accessed November 19, 2017. http://www.motherjones.com/kevin-drum/2011/10/yes-indeed-income-inequality-really-growing/#

Additional Reading:

How can we tell that there was a case of structural violence in the archaeological record? We know the violence of concentration camps due to individuals living in these conditions and their liberators witnessing the atrocities, so if we don’t have these accounts is it possible to see structural violence in the archaeological record?