CHAPTER THREE

WHEN OLD TIME MUSIC LEFT THE MOUNTAINS:

THE ‘DISCOVERY’ OF HILLBILLY MUSIC

“Ha, you think it’s funny/ turning rebellion into money”

—The Clash, “White Man in Hammersmith Palais,” 1978

As described in Chapter Two, authoritarian governments have realized that patriotic participatory music has the power to unify. They have carefully harnessed the power of participatory music to induce group solidarity amongst their populaces, bolstering a sense of nationalism over localized interests. They have also privileged urban, professionalized musical formations as a way to control music communities within their own borders. Attali (2002) writes, “The French monarchy’s repression of regional music, white music executives’ ostracism of black musicians, the Soviets’ obsession with peaceful, national music, the systematic distrust of improvisation: all of these show the same fear of the foreign, the uncontrollable, the different” (p.x). As for the history of Appalachian music, there is not a pattern of hegemonic interests that have forthrightly stamped out the regional music.[1] Formalized state power was not needed to cause the erosion of the power of old time music. Rather, through the influence of racist and commercial interests, old time music has undergone many changes that have transformed it from the powerful, regional music that was embedded with the values present in pre-capitalist, Gemeinschaft mountain communities, to a mere shadow or caricature of its initial form.

The transformations of Appalachian music have been influenced by popular stereotypes about the hillbilly, which have changed over time. In recent decades, urban sophisticates have snubbed the hillbilly and his simple crudity, perhaps even fearing his unabashedly rebellious, self-sufficient, anti-bourgeois attitude. Negative portrayals in the media abound.[2] Yet this classist stereotype was not always the dominant image of the mountain dweller. During the first half of the 20th century, politicians, university administrators, and corporatists were able to use the hillbilly music for their purposes—namely, accruing profit and strengthening the nationalist myth of white racial supremacy. By promoting the myth that in the rural mountain hollers lived the descendants of the purest Anglo-Saxon blood, a white supremacist case for the study of Appalachian music and culture persisted.

This chapter will trace selective historical moments of Appalachian music in the 20th century, which was characterized by the appearance of early Northern intellectual ‘song catchers,’ dominant racial ideologies in a time of mass immigration and industrialization, paradigmatic advancements in technology, and the emergence of music festivals and the ‘old time industrial complex.’ The chapter will end by discussing the crossing over of Appalachian music into the final frontier: northern cites. During the folk music revivals of the 1960s and 1970s, Appalachian music served an important ideological purpose for the leftist musical community. Throughout the 20th century, as Appalachian music became commodified, many factors and ideologies contributed to its decontextualization and politicization, which ultimately served to tarnish the potency of the music’s implicit messages that contradict corporate capitalist rationalism. At the same time, the spreading of this normatively participatory musical form was able to bring a sense of community to urban leftist circles, which, as I will show in Chapter Four, continues today in the communities of neo-revivalists.

SONG CATCHERS, RACIAL PURITY, AND TOL’ABLE DAVID

In the late 19th century, local color writing became a veritable literary mode in which northern, urban journalists and authors traveled to other areas—be they rural, western, or southern—with the aim of writing entertaining, exaggerated tales of local customs for northern urban audiences (Rowe 2008: 137). Local color writers ventured into Appalachia and published accounts that tended to portray Appalachians as backwards savages, not unlike modern media representations. In 1873, a lowland-born Kentuckian named Will Wallace Harney described the mountaineers as “rude rustics” that were cursed with “marked peculiarities of the anatomical frame” (McNeil 1989: 45). Many early color writers considered Appalachians to be deformed specimens of the white race because of the isolation and roughness of living in the mountains as well as contact with Native Americans and the assumption of miscegenation (Shapiro 1978).

Yet a single essay published in the Atlantic Monthly in 1899 by Berea College founder William Goodell Frost shifted the discourse on how outsiders should conceptualize Appalachians. The goal of his essay, entitled “Our Contemporary Ancestors in the Southern Mountains,” was to garner monetary support for his fledgling college. As an Appalachian exceptionalist, his 1899 article helped to ignite the myth that Appalachia was racially homogenous and pure: “To-day there are in the Southern mountains…Americans for four and five generations who are living to all intents and purposes in the conditions of the colonial times!” (p. 92). His article successfully established the importance of Berea College in that it plays an important role in educating the ‘modern Anglo-Saxon ancestor.’ In this context, Appalachians are revered for their imagined racial and patrimonial purity at the same time they are gawked at for their ‘backwardness.’

The first musical explorations of Appalachia were motivated by this myth of the white racial purity of the mountaineers. During the 20th century, dozens of Northern, university-affiliated ‘song catchers’ traveled into mountain hollows with musical notepads or prototypical recording devices in order to capture, study, and archive thousands of Appalachian tunes and ballads. Cecil Sharp was the first song catcher to publish a major collection of Appalachian ballads. As an Englishman seeking to find preserved English ballads in the Appalachian Mountains, he embarked on an “English nationalist project” (Thompson 2006: 72) from 1916 to 1918. His research ignored black musicians entirely as well as their contributions to music in the mountains, as evidence of such weakened his findings of Appalachia as a land that had preserved old English ballads. The racial and nationalized motivations of Sharp’s work proved to influence the focus of subsequent song catchers.

However, dominant racial ideologies at the time were such that subsequent song catchers did not need to rely on Sharp’s example to explore Appalachian music through the lens of racial purity. Anglo-Saxon superiority was a subject at the forefront of the public imagination at the turn of the 20th century, when immigration from central, southern, and eastern Europe was accelerating. Racial hierarchies were imprinted in the minds of even the most earnest Progressive era reformers.[3] One response that white elites had to the ‘unsavory’ arrival of millions of immigrants was an increase in “all things folk” (Osteandorf 2004: 201). Beginning in the 1870s, they created folk societies that lauded the culture of their white ancestors, no doubt relying on revisionist history and an explicit nationalist agenda. Song catchers of Appalachian music were thus a part of the rising tide in popularity of a whitewashed American folk culture. Most song catchers chose to ‘selectively collect’ the ballads they felt were rooted in old-world tradition. They largely ignored other styles of Appalachian music, many of which were created in the new world by a more diverse crowd, notably African and African-American slaves. In the immigrant-weary Progressive Era, during which segregation was legalized in the South and racial violence abounded, “the attitudes, expectations, and findings of the song catchers regarding the protection and continuation of an Anglo-racial heritage was consistent with the American attitude at the time” (p.195).

https://youtu.be/1Jfv08XG5Z8The film industry supported the idea of Appalachia as a bastion of wholesome Anglo-Saxon tradition. Following the urban turmoil that so characterized the Progressive Era, the roaring 20’s was positioned as a golden age. The economy was booming, jazz was blossoming, and the entire country was thriving in a fit of emotional patriotism. In 1921, the Henry King-directed film Tol’able David premiered to immediate, resounding success. Tol’able David presented an idealized version of rural life that seemed quintessentially American. While a full fifty percent of the country lived in urban areas at the time, they were nonetheless enthused by the nostalgic portrayal of rural Virginian life and the countless shots of farm animals and dirt roads that contradicted urban life in the most charming, visceral way (Williamson 1995: 141). The first title card in the silent, black-and-white film reads, “Behind three great ranges of mountains lay the pastoral valley of Greenstream.” Shots of Virginia valleys transport the urban viewers across time and space, back to the Gemeinschaft, pre-war, pre-industrial era in United States history, before Progressive Era immigration and before the social upheaval instigated by the Civil War. There is not one person of color in the film, not even in a role of a slave or domestic servant.[4] According to one viewer, the film left him with “nostalgia for a place I had never been, a time I never knew” (Coppedge 1982: 42). The Kinemons—the fictional family around which the film is centered—are presented as a Christian, hard-working nuclear family that lives in a distant mountain hollow, located in the annals of pre-industrial American yeomanism. One theory for the box office success of the movie is that:

There was in the city a reservoir of unresolved guilty nostalgia for America’s rural past, just waiting to be focused and released by Tol’able David’s fond agricultural romanticism… Barthelmess made a vast American urban audience…feel good again about home and white bread. (Williamson p.183)

Spirits high from the First World War, white urban Americans “no longer needed to look to Europe to legitimize their cultural heritage” (Osteandorf p.199). They had only to observe the emerging ‘hillbilly’ film genre to believe in the nobility of their modern ancestors in the way that their academics and bourgeois class had been doing for decades. It should not come as a surprise that director King bought the screenplay from D. W. Griffith, who directed the 1915 white propaganda film The Birth of a Nation.

The work of color writers, song catchers, and films such as Tol’able David have led to seismic shifts in the popular perception of the hillbilly. At times, the mountain dweller has been seen as savage and offensive to the modern lifestyle, and at others as naïvely pure because of an imagined cultural preservation. In the 1960s, during the post-war era of industrial prosperity and the rise of consumer culture, Appalachia was seen as anachronistically pre-industrial and impoverished, and the ARC was thus established. The moment in which the hillbilly was popularly seen as a carrier of Anglo-Saxon cultural heritage was indeed but a moment, as instances of ridicule due to perceived class differences both pre- and post-date the ethnic purity stage of the early 1900s. Thus as we trace how Appalachian music left the mountains, we must keep in mind how Appalachia was imagined by academics as well as the American public.

PRESERVING VS. EXPLOITING CULTURE

Did the visits of the early 20th century song catchers mark the beginning of the exploitation and eventual commodification of Appalachian music? Or were the song catchers respectfully documenting early American folk songs so that they could be appreciated for generations to come? This question is pivotal to the 2000 movie Songcatchers, which portrays a fictional female song catcher’s voyage into rural Appalachia during the 20th century. In the movie, local Appalachian musician Tom provocatively challenges the song catcher’s intentions by impassionedly arguing to another character, “First it was coal and lumber, now they wanna come in and steal our music.” While Tom may be a fictional character that was penned long after the era of the early song catchers, he has a point: given the lengthy history of exploitation of Appalachia’s natural resources—which continues to this day in the form of mountaintop removal and toxic coal ash storage, to name just two examples—might this early song catching constitute a subtle form of cultural exploitation, especially considering the song catchers’ explicit white nationalist agenda? Before Appalachian musicians were paid for their musical contributions, they were objectified for their musical abilities, which they were happy to share, but in the end these contributions greatly profited white hegemons. Yet on the other hand, as will be discussed on Chapter Four, for many modern urbanites, old time music has been an antidote to digital-era urban weariness and therefore the exploitation of the musicians has not yielded universally negative results.

It is erroneously simplistic to condemn exclusively outsiders for exploiting the music of the mountaineers. On occasion, native Appalachians were the song catchers, rather than educated outsiders who meant well, but undoubtedly failed to understand the complexity of the culture that created the music. Virginia-born A.P. Carter is one of the most notorious and successful examples of a native Appalachian song catcher. In the 1920s, A.P. traveled around Virginia, Tennessee, and Kentucky to collect traditional tunes and lyrics. In 1927, he and his band The Carter Family started recording music, and according to some, singlehandedly ignited the American country music genre (Peterson 1997). A.P. secured the newfound fortune of his family’s band by copyrighting the songs they had scavenged, learned, and then recorded. In other words, A.P had sought out authentic Appalachian tunes, and then commodified them by “entering the system of capitalist exchange, where [they] can be used to generate surplus value” (Taylor 2007: 282). A.P. and other Appalachian artists were undoubtedly motivated by the pursuit of profit and success in the burgeoning Appalachian music industry.

Moreover, the debate between cultural preservation versus exploitation intensifies when one considers how Appalachian musicians were incentivized to alter the music. Because native Appalachians were well versed in the authentic sounds of old time music, they were best equipped to manufacture its sound via original songs. Porterfield (1992) describes how record companies took advantage of this fact:

Pressured to produce material that was new yet somehow authentic to their temperament and traditions, aspiring rural artists such as Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family fell back on two obvious sources: either they dredged up old, half-forgotten relics of the past, or they composed original songs that sounded like the old ones—music that connecteD with the past and extended the tradition. (Porterfield 1992: 99, as quoted in Peterson 1997: 35).

Thus as Appalachian music became commercialized, Appalachian artists became pressured to forge a sense of tradition, either by exploiting fellow Appalachian musicians who would never have a chance at recording for a record industry, or by creating new songs that attempt to capture and market Appalachianness. Thus native Appalachians were motivated to play a large role in the commodification and decontextualization of their own music.

TECHNOLOGY AND THE MUSIC INDUSTRY

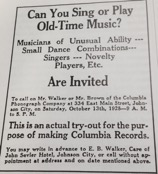

This 1928 Columbia Records advertisement shows an early call to arms for Appalachian musicians (Encyclopedia of Appalachia, p.1154).

The earliest form of the objectification of Appalachian music was its transmission into sheet music, which was not the handiwork of nefarious Appalachian outsiders. The earliest known printing of Appalachian music in the form of broadside ballads, which were “sheets of paper peddled on the street that were printed with the song lyrics but without the melody” (Pen 2011a: online). While this was the first possibility for Appalachian tunes and ballads to become detached from their social context and sold in a fixed form for money, broadside balladry rather served to disseminate ballads and tunes within Appalachia, to folks that would have to be familiar with the tune in order to successfully make music out of the broadside sheet. Thus while broadside balladry did not lead directly to the commercialization of Appalachian music, they did mark the first step in using Appalachian music as a tool used to accrue profit. It was also the first time that the music was finitely divorced from its ‘natural environment’ and allowed to enter other social or commercial contexts.

The advancement of technology in the form of the record and the radio led to such a monumental transformation in the possibilities for cultural profiteering of folk music that we might call it a paradigm shift. It was the recording industry that has allowed for musical culture to be anything other than live, whether presentational or participatory. Before the record industry, the highest degree of the commodification of music was live, for-profit presentational concerts and the selling of sheet music. Now, an entire music industry profited off of mass production and distribution of records, and a new career of the touring musician was thus made viable due to the creation of popular music.

On the one hand, the generous availability of this music technology has democratized all music, whether folk or classical, and has expanded musical audiences across class boundaries. Most would argue that in some sense, this is a welcome development in the sharing of culture. On the other hand, what have we lost by bringing music into the commercial realm? What happens when, aided by advancements in technology, music becomes a “music-commodity?” (Taylor 2007: 284). The reification and later fetishism of music have played parts in repurposing Appalachian music. Whereas all music, including Appalachian music, used to be rooted firmly in the social world, mass technology has allowed it to become a commodity separated from its original social world and produced in contexts however dissimilar from its original environment. Furthermore, it is assigned many romanticized values, which explains its profitability.

Fordism and the rise of the consumer society greatly affected folk music. The mass production of musical instruments eroded the need for Appalachians to fabricate instruments for themselves. While this likely led to a decrease in the amount of skilled Appalachian instrument makers, it also affected the music in another way: the guitar became available through mail order and slowly became a canonical Appalachian instrument for the first time (Peterson 1997).[5]

As indicated above, record companies played a large role in altering Appalachian music. Looking to revive slumping record sales, record companies tried a new approach of recording local artists in rural regions in the South, with the intention of inviting successful musicians whose records had sold well to subsequently record in a larger city and become a professional Appalachian musician on perhaps a national scale (Peterson 1997). Record companies were looking to expand their markets into the countryside, hoping that “white farmers and townsfolk would be more likely to buy phonograph record players if their preferred kind of music played and sung by one of their own was available on phonograph records” (p.42). In 1923, Fiddlin’ John Carson from northern Georgia became the first Appalachian musician to be recorded for commercial, non-academic purposes. His records, which were sold in Atlanta, quickly sold out.

Carson’s success inspired 1927-1929 Virginia ‘Bristol Sessions,’ as they are now known, which were even more successful recordings of some nineteen groups spanning the gamut of Appalachian music, of which the Carter Family was one (Olson 2006). The Bristol Sessions are by some considered to be the “Big Bang of Country Music.” The extent to which black musicians were included in these sessions is unclear, and perhaps doubtful. While record companies did include a variety of black musicians in what are now referred to as race records, the notion of black hillbilly music was regularly rejected by record companies because it contradicted the myth and audience expectation that mountain men were still the snow white Anglo-Saxons that they had been constructed to be for decades (Peterson 1997).

Due to the sudden commercial viability of an Appalachian music industry, it was during this time that modern music industry concepts such as musical touring, song publishing, and songwriting began to include Appalachian musicians (Peterson 1997). In its most original formation, as I have discussed, Appalachian music was not performed by professionalized musicians for profit. But new technologies such as the radio and phonograph record industry transformed career possibilities for musicians. For the first time, Appalachian musicians such as Fiddlin’ John Carson and others became professional, traveling musicians that profited from shows at town halls and school auditoriums (p.23). Another way that technology encouraged Appalachian musicians to shift from tradition was the concept of song publishing. Whereas folk songs are not owned by any one group or person and are traditionally memorized without the help of physical notation, the music industry profits from the privatization of music—removing it from the commons—and by marketing a musician’s stage presence that is based on a cult of personality. Lastly, record labels hired songwriters for Appalachian musicians in order to secure an adequate turnover of new material. Introducing hierarchical specialization to old time music, many native and non-native Appalachians alike were employed as full-time professional music songwriters (p.23). Through new technology, Appalachian music left the mountains, while professionalization and bureaucracy allowed it to create handsome profits. The process of repurposing old time music for a mass audience changed the music’s character:

arrangers often refashioned traditional texts and tunes…Unavoidably, the versions of Appalachian material presented to broad-based, non-native audiences were different from the original sources…Such mainstream versions of Appalachian folk music commonly became more popular than traditional versions and styles. (Olson 2006: 1111)

Thus as Appalachian music left the mountains, its form, content, and character changed to suit the needs of its clients in the record industry and in cities, gradually displacing authentic Appalachianness. The folk revivalists of the 1950s and beyond were limited in that most of the versions of tunes they heard did not come directly from native musicians: much of the time, they were inspired by tunes that sounded authentic, but had in fact been re-written to fit popular musical tastes while still holding onto a fetishized notion of Appalachian authenticity and the cultural baggage that comes along with it.

Barn dances, which were staged musical and theatrical acts that exaggerated Appalachian dress and music, began on the radio in 1932 and continued decades into the television era. These nationally popular acts provided steady work for the aspiring Appalachian musician, but at a steep symbolic cultural cost. In order to appeal to advertisers and audience expectations, musicians often had to exaggerate the differences—both real and imagined—between themselves and the audience, thereby culturally prostituting themselves:

The stereotype inevitably left far-flung audiences with negative and inaccurate impressions of Appalachian people. These barn dances particularly misrepresented two aspects of the region’s culture: Appalachian speech and Appalachian clothes. Musicians were encouraged to exaggerate their regional speech and to wear standardized hillbilly dress, including bib overalls and straw hats. (Olson 2006: 1114)

Clearly, at this point in the history of Appalachian music’s commodification, the debate between cultural preservation versus exploitation remains salient.

MUSIC FESTIVALS AND THE OLD TIME INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX

Dating back to the 18th century, Appalachians had lively traditions of public festivals that consisted of “agricultural fairs, court days, camp meetings, gospel conventions, community workings, shape-note singings, and fiddle contests” (Pen 2011b: online). Thus, in traditional Appalachian culture, public festivals were firmly rooted in various aspects of community life, of which musical heritage was merely one aspect. However, just like Appalachian music itself, Appalachian heritage festivals have often become commercialized and decontextualized for the pursuit of profit. These festivals have been run by outsiders who repackage Appalachian culture “as a generalized example of traditional life for an audience usually comprised of people from the region as well as cultural outsiders” (Pen 2011b:online).

The first commercial, outsider-funded Appalachian music festival was the White Top Festival, which took place in Grayson County, Virginia, in 1931. The founders chose to center the festival on Appalachian music’s roots in Great Britain, similar to the previous work of Cecil Sharp and the early song catchers. This myopic, hyperbolized focus on the purity of the music’s Anglo-Saxon heritage was one way that this festival distanced itself from the actual, diverse character of Appalachian music, which set the tone for sequential festivals. Another way White Top did this was by charging admission for the festival, which excluded many local residents who could not afford an admission ticket. Ironically, at a festival that celebrated the music they produced in their communities, many locals resorted to standing outside festival boundaries to listen in. Furthermore, due to an unabashed white supremacist agenda of the festival, black fans were prohibited from entering festival grounds. The only black bodies to enter the festival were the servants of Eleanor Roosevelt, who visited the festival in 1933—never mind that the banjo originated in West Africa.

A 2007 interview with Appalachian musician Stan Gilliam indicates that these patterns have continued into modern Appalachian music festivals. While the extent to which Gilliam is an Appalachian insider is debated, as he comes from non-Appalachian North Carolina and his knowledge of Appalachian music stems from listening to records of Fiddlin’ John Carson as a child rather than learning it orally/aurally within the context of its original culture, he nonetheless takes issue with the modern Appalachian music festival scene:

My views on the contemporary ‘old-time scene’ are somewhat jaded. In fact, I hate it…As a southerner with genuine traditional music in my blood, I sometimes resent the star system of carpetbagger musicians who have co-opted traditional music and becomes its arbiters…I see the old-time scene as a somewhat artificial subset of the grander ‘folk and traditional culture,’ which includes arts and crafts, language, beliefs, foodways, and so on. The festival scene has its myopia and even a meanness which is out of keeping with the generous spirit of the real old timers who seldom expected to be known outside their hometowns. (Wish 2007: 39)

Therefore, festivals that took place even within the mountain south decontextualized Appalachian music for the sake of profit. They also saw the festivals as opportunities to pursue the ideology of white supremacy, which is inextricably linked to the success of capitalism.

At the same time that Appalachian music was decontextualized and commodified through the radio, the recording industry, and the music festival industry, old time musical traditions gained fans and benefactors that belonged to the “top one percent.” As indicated above, Eleanor Roosevelt attended the 1933 White Top Festival to show her interest in the new cultural movement of appreciating Appalachian music and culture through a whitewashed lens. Whereas Roosevelt was more a symbolic supporter of this movement, Henry Ford was an actual benefactor of Appalachian music.

Henry Ford played a key role in the automobile industry, which ushered in a new era of consumer culture, as mass-produced goods could be shipped more cheaply and travel and tourism became more feasible. However, he was likely tortured by his role in accelerating modernity, as he saw the modern city as “unnatural,” “twisted,” and diametrically opposed to the countryside, wherein lies “the real United States” (Peterson 1997: 60). Importantly, Ford blamed the vices of the city on “alcohol, tobacco use, and sexual license” as well as “African Americans, recent immigrants” and Jews (p.60). Ford, like many scholars before him, looked to Appalachian culture as the last bastion of ‘pure’ Anglo-Saxon musical and dance traditions. He invested in old time fiddling and square dancing on a national scale, fancying himself to be a noble cultural ambassador. He held fiddling competitions across his auto dealerships nationwide. His 1926 national competition attracted some 1,875 competitors. Peterson attributes Ford’s extensive efforts to popularize these art forms as the reasons that old time dancing briefly became “an urban rage” (p.61) as well as the reason it was included in the dance curricula of thirty-four colleges. Yet the Ford-driven hype gradually died down and cities never shook their attraction to their ‘sin-and-jazz’ ways. It remains salient in the history of the commodification of Appalachian music that a musical formation so originally incompatible with capitalism could be esteemed so highly by Henry Ford, a patriarch in the new order of corporate capitalism.

THE FOLK MUSIC REVIVALS OF THE 1950s AND 1960s:

THE POLITICIZATION OF APPALACHIAN MUSIC

The folk music revivals of the 1950s and 1960s brought Appalachian music into urban areas and were qualitatively different than the previous commercial processes that had exported Appalachian music from the mountains. Although the revivalist musicians were attracted to Appalachian music not by commercial but by personal and political interests, these revivals nevertheless occurred after the paradigmatic changes in technology took place. At this point in music history in the United States, the paradigm was that commercial music—even folk music—was privately written and owned, and no longer a product of the commons, as was original Appalachian music. This technological context and other limitations, such as the politicization of music, continued to fetishize Appalachian music, despite the best intentions of the leftist, communitarian-minded revivalists. These musicians were also unable to resolve the tension of bringing rural mountain music into the modern metropolis as well as the tension of becoming famous—and rich—as a folk musician.

The folk revivals of the 1950s and 1960s were successful in transforming the terms ‘folk,’ ‘folk music,’ and ‘folk song’ into household words (Cohen 1995). As ‘folk music’ became a veritable musical genre, the concept that much of the music originated in Appalachia began to disappear, and instead it seemed to be displaced by an unknown rural, pre-modern culture whose history was unknown. Many consider the beginning of the second wave of revivals to be in 1958, when the Kingston Trio recorded “Tom Dooley,” which has its origins in Watauga County, North Carolina (p. 16). “Tom Dooley” had previously been ‘discovered’ by song catchers such as Alan Lomax and Frank Warner. Years later, the Kingston Trio heard one of these song catchers’ recordings and then harmonized the catchy tune to resounding, chart-topping success. Even though the band was curiously comprised of three college-educated young men who were raised in Hawaii and California, the fact that they sang about a murder committed on a mountain in Tennessee did not hurt their success. This 1958 chart-topping success caught the attention of record companies and young listeners alike, singlehandedly driving the demand for the most commercialized folk music scene yet. Soon enough, musicians such as Pete Seeger, Bob Dylan, and the New Lost City Ramblers catapulted to the highest levels of celebrity in the music industry.

One effect of the creation of the folk industry was the further detachment of old time music from its original values and origins. The emerging folk music scene became popular amongst the young, college-educated crowd, who appropriated the music and thus transformed it by “aesthetic colonization” (Grunning 2006). Ironically, revivalists who tried to remain authentic and respectful by learning and teaching lessons about Appalachia and its culture, such as Pete Seeger, only served to expand the revival’s penetration into the middle class psyche. Rosenberg (1993) writes:

Folk music revivals…constitute an urban middle-class intellectual community that, in seeking alternates to mass culture music, develops an interest in, appropriates, and consumes the music produced by the people for whom informed scholars act as advocates. Revivalists, in transforming traditions, represent the established political and social agendas of the group from which they emerge in contrast to the agendas represented by the nonrevival folk groups in whose music they are interested. (p.19)

Therefore, reviving folk music in an urban, middle-class context inherently reshapes the musical community by thrusting folk music into the realm of academic, enthusiastic musical interpreters, who cannot help but appropriate this musical form they respect so dearly. This deepens a divide between the urban, intellectual revivalist and the Appalachian mountaineer musician. Relatedly, folk music’s popularity with a student fan base also led to its politicization, specifically with leftist ideology. As compared to more blatant commercial repurposing of old time music, leftist ideology may be more attuned to the original, nearly classless context in which old time music originally formed than to more blatant commercial uses. Old time music originated in a culture in which there was not much social stratification based on education or income. However, the music was not properly “working class” as it originated in a context before social relations were organized around class tensions. Nor was old time music forthrightly political until the birth of the protest movement genre that grew out of exploitation in the coal mining industry, when a new genre of Appalachian music was born. The revivalists insisted on endowing the music with the plight of the working class. Revivalist Roy Berkeley (1995: 188) writes that the revivalists attached leftism to folk music in a downright pious way. Additionally, much has been written about the incompatibility of the immense celebrity and wealth of musicians such as Woody Guthrie and Bob Dylan while they maintained their public image as anti-consumerist, pro-community folk singers of the people (Pratt 1990; Hampton 1986).

NOUVEAU FOLK AND THE NEO-REVIVALISTS IN THE DIGITAL AGE

I refer to the music produced by 21st century neo-revivalists as nouveau folk, which is a pretentious, pseudo-academic term that satirizes the intellectual, college-educated ‘aesthetic colonization’ that has so dominated the revivals and neo-revivals. Mumford and Sons are one example of nouveau folk, as they try to appear ‘authentically’ folk in terms of aesthetics and instrument choice, despite that they are a London-based band that merely incorporate the banjo and double bass into their alt-rock sound. Yet there is another nouveau folk community, which is rooted in less commercial, urban, intellectual communities that romanticize old time music. The second half of Chapter Four will show a case study of nouveau folk in Brooklyn.

NOTES

[1] However, Attali’s mention of the ostracism of black musicians by white music executives is indeed present in the history of old time music’s commodification.

[2] To name one example, Saturday Night Live ran a segment in the early 2000s called “Appalachian Emergency Room,” which mocks Appalachia’s supposedly inadequate healthcare, provincial accents, poverty, and general ‘white trash-ism.’

[3] We recall Jane Addams’s writings about the need for settlement houses to aid Italian immigrants, which she believed to be an inferior race.

[4] The absence of slaves and domestic servants in this film is historically accurate in the fact that very few middle-class mountain families would have owned slaves or hired domestic servants. Yet the complete absence of people of color is suspicious.

[5] The guitar also became canonical in bluegrass and country music traditions, and all three music genres have roots in the same ballads, tunes, instruments, and general geographical origins. They also share a common history of commodification by the recording and radio industries in the 1920s.

Next: Chapter Four

Contemporary Old Time Music Scenes in Boone and Brooklyn

Chapter Five

Conclusion, Afterword, References

Previously: Chapter One

Introduction to Appalachia

Chapter Two

Old Time Music: Its Original Context Within Appalachia and Its Participatory Nature