CHAPTER TWO

HEAVY METAL

Understanding what heavy metal is, as a genre, is impossible without understanding the history of heavy metal and how it came to be ubiquitous as part of the greater rock music umbrella. Prior to this however, there must be an understanding of the role that genre plays in cultural analysis — both what ‘genre’ is, and how the term is used.

There is a long academic discourse on genre, some agreement across disciplines. Lena and Peterson identify genre as “plac[ing] cultural meaning at the forefront of any analysis of category construction” going on to say that it “has potential and significant general utility across domains” such as film, music, literature, and even cuisine.[17] Italian musicologist Franco Fabbri describes musical genre as “a set of musical events (real or possible) whose course is governed by a definite set of socially accepted rules.”[18] Gabriele Marino, expanding on Fabbri’s work, declares genre to be “a socio-culturally connoted and a functionally justified music style (the ‘compositional norm’).”[19] In both Marion and Fabbri’s position on genre, a key differentiation between style and genre is being made to distinguish a ‘typology’ of music (electronic, hip-hop, rock) from the culturally loaded terminology describing certain sonic movements within those typologies (EDM, trap, and Emo for example). Marino explains this as: “genre names are nontransparent labels just like ‘trap’ and have actually nothing to do with music; the elements which participate in the naming of the genre say nothing about the musical features, but maybe say everything about the pragmatics of the music.”[20]

Bourdieu distinguishes genre as merely a widely applied taxonomy for dictating levels of class structure in cultural output. In Bourdieu’s view, people are drawn to what is societally deemed appropriate for their class. He succinctly writes: “social subjects comprehend the social world which comprehends them.”[21] This can be translated to metal, where “class” can be interpreted as a strictest reading of genre in the sense that Lena and Peterson use it. In metal, “hair metal” (synonymous with “glam metal”) served to separate and delineate the music it was applied to from that of true heavy metal; however, “hair metal” got picked up as the descriptor for bands like Def Leppard and Poison, aligning them as being part of yet another (sub)genre in metal. By finding a middle ground between Fabbri’s socio-temporal definition of genre, and Bourdieu’s class-based definition, the widely-used names for subgenres of metal begins to be clearer, as does the term “heavy metal” itself. Using these understandings of genre as a guide, an (overly) simple description of heavy metal could be given as such: a genre that encapsulates a subset of guitar-based rock music that focuses on speed, distinctive aesthetic, and prodigious noise.

Across a wide reading of critics, scholars, and musicians alike, there is not ‘true definition’ of heavy metal, however, there is a relative consensus as to why and where the genre originated.[22] Heavy metal[23] developed out of the latter half of 1960’s rock music, a time where longer and more intricate compositions overtook simpler ones from earlier in the decade. The Beatles darker turn towards the 70’s as well as Hendrix, the Yardbirds, and a revitalization of blues-inspired guitar playing all influenced the birth of metal. Weinstein specifically points to volume as being the cohesive difference between the “jangly” rock and roll of the late 50’s and early 60’s, and the massive sound of Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath in the early 70’s by saying that: “the essential sonic element in heavy metal is power, expressed as sheer volume. Loudness is meant to overwhelm, to sweep the listener into the sound, and then to lend the listener the sense of power that the sound provides.”[24] Berger, Moore, Overell, and Walser all reference the role that volume played in metal’s development as a genre.

It is not as important to this work to understand the exact originator of metal, be it Zeppelin, MC5, Black Sabbath, or any number of similarly minded, chronologically congruous (mid-1960’s to the mid-1970’s) contenders for the throne of “first heavy metal band”. However, understanding the role that metal played in the culture of the 70’s, 80’s, and 90’s is crucial to decoding nu-metal’s eventual place in American society. The visual, sonic, and verbal coding of metal was unique in music when it first came around. As metal splintered into sub-genre upon sub-genre, shared codings were much of what kept the sub-genres from developing into full-fledged genres of their own right. Much of Chapter 3 will be spent discussing the aesthetics of metal and nu-metal, both in meaning and in practice.

SUBGENRES OF HEAVY METAL

An essential part of understanding the various subgenres of heavy metal comes from understanding the codings, or shared features, that span different facets of metal. When looking at shared codings, volume level, verbal, visual, and clothing cues are the strongest uniting factors. Each of these is far more distinct than in many other genres, partially contributing to a widely unifying capacity. Arguably three of the four of these cues are fan-propagated, as documented in Weinstein’s chapter “Digging the Music: Proud Pariahs.”[25] The hegemony of several aspects of metal culture manifests in these similar codings and factors, and is present across all non-technically specific literature pertaining to heavy metal. Beyond this, every critic and scholar are united on the concept of a shared culture that, while driven by volume level, verbal, visual, and clothing cues, is animated in large part by the vast audience metal captivated.

Across metal’s many subgenres, the most noticeable non-fandom based example of collective culture comes in the form of nomenclature. There is practically no other genre in which one can surmise an idea of a particular bands’ sound by seeing their name, without actually encountering their music. Across metal, bands like Megadeth, Slayer, Anthrax, Poison, Black Sabbath, Iron Maiden, AC/DC, and later Puddle of Mudd, Saliva, and Insane Clown Posse, employ a deliberately grotesque, medieval, occult, gothic, and juvenile, vocabulary that by association has primed the listener for what they’re about to hear.[26] Each of the aforementioned names functions as a signifier for something outside of convention or any sense of normalcy, and while that may seem like a fairly large and diverse set of categories, but it is remarkable how few bands fall outside of any of them. There is a long tradition of risqué or controversial band names in all genres of rock and roll (see: Joy Division[27]; many punk bands), but a disproportional amount come from bands that play various forms of heavy metal. These names function as a collective demarcation system for metal bands; it is extremely rare that bands do not follow this custom, even on the fringe of metal subgenres.

Often specific subgenres will have their own naming conventions that fall in line with those of metal more broadly. Grindcore, a particularly fast and sonically brutal branch of metal is an example of adherence to a fairly rigorous schedule of naming that goes far beyond what is seen in other metal subgenres. Among others, acts such as: Anal Cunt, Cripple Bastards, Napalm Death, Pig Destroyer, Cephalic Carnage, Circle of Dead Children, and Carcass, participate in the usually physically grotesque naming conventions that link the subgenre together.[28]

Throughout metal, not only are the names lexically stylized, but also often they are similarly visually stylized, usually in a gothic, jagged, or improbable manner.[29]

The poster for 2010’s edition of seminal metal festival Maryland Deathfest. The headlining acts are allowed to use the stylization of their name, each one acting an identifying logo.

This was especially true in the early days of metal, through the era of glam and thrash. Looking at the biggest names in metal at the time: Iron Maiden, Kiss, Pantera, AC/DC, Black Sabbath – each one brings to mind a distinctive logo almost regardless of whether one is a fan or not. Indeed, through the power of 80’s metal’s prodigious merchandising, it became that the logos and name stylizations of metal bands were more culturally ubiquitous than the music. A prime example of this later in nu-metal comes from Korn, famous for their “r” being backwards and capitalized. This can be viewed as commentary on the concept non-conformity in juxtaposition with grunge.

Beyond vocabulary, apparel was and continues to be an immense part of metal culture’s fan hood and performance. The fashion in and around metal is particularly distinctive, especially when considered next to other western genres. Jazz, country, pop, and blues, for the most part, have some common uniforms outside of stereotypical garb expectations[30], whereas metal has phenomenally recognizable accoutrements.[31] Leather vests, black jeans, underground band t-shirts, black boots, tattoos, unorthodox piercings, and several other visual signifiers traditionally represent metal culture.[32] Heavy metal apparel, as is often found in any underground or specific genre scene, tends to be specific in its look, with associations about certain fandom often able to be deduced from a passing visual examination. Nu-metal had its own version of this subgenre specific apparel that will be delved into later. It had quite a bit to do with the hybridization between metal and rap style, and also nu-metal’s non-conformist, transgressive nature.

Beyond vocabulary, apparel was and continues to be an immense part of metal culture’s fan hood and performance. The fashion in and around metal is particularly distinctive, especially when considered next to other western genres. Jazz, country, pop, and blues, for the most part, have some common uniforms outside of stereotypical garb expectations[30], whereas metal has phenomenally recognizable accoutrements.[31] Leather vests, black jeans, underground band t-shirts, black boots, tattoos, unorthodox piercings, and several other visual signifiers traditionally represent metal culture.[32] Heavy metal apparel, as is often found in any underground or specific genre scene, tends to be specific in its look, with associations about certain fandom often able to be deduced from a passing visual examination. Nu-metal had its own version of this subgenre specific apparel that will be delved into later. It had quite a bit to do with the hybridization between metal and rap style, and also nu-metal’s non-conformist, transgressive nature.

Beyond apparel, hairstyle was a seriously significant part of metal, enough so that glam metal is often referred to as hair metal, due to the outrageous locks sported by Kiss, Bon Jovi, Mötley Crüe, and Poison among others. In his book about growing up a metal-head, Chuck Klosterman places an emphasis on the importance of hair in metal in the 80’s, a sentiment Deena Weinstein echoes. Both writers indulge an argument that unruly hair was a response to the socio-concept of the ‘traditional American male’ in the late 70’s and early 80’s. Additionally, it functioned as a response to the comparatively clean-cut look of commercial rock at the time, metal’s de facto enemy.[33] Indeed, hair has remained a significant aesthetic expression in metal. The black/Nordic metal revival on the 2000’s features a number of bands, including acts like Liturgy and Deafhaven, both of whom have members that maintain healthy locks. Later on, as dreadlocks became common in nu-metal they signified not only a rejection of the contemporary pop-sphere (N*SYNC, Backstreet Boys), but also nu-metal’s cultural transgression and connection with black culture through hip-hop.

SONIC COHERENCE ACROSS SUBGENRES

In terms of musical codings, each various subgenre of metal that spun off retained certain elements of the initial British and American waves of heavy metal. Grindcore took the goriest and darkest aspects of metal and turned them into their own subculture, replete with bloodstained logos and lyrics entirely about various mutilations.[34] Glam (also known as lite) metal took some of the buoyant sonic traits of pop rock of the 70’s and early 80’s and sped it up and added distortion, fusing the soft, emasculated California surf-rock aesthetic and a louder metal lineage. Nordic Black Metal took the premise laid down by British heavy metal bands and expanded the cult, mythological, and Satanic elements spawning infamous bands like Burzum. Outside of these, there are prominent entries from Christian metal, doom metal, metalcore, prog metal, stoner metal, and alternative metal among others, each of which has further subgenres. It is perhaps helpful to imagine a taxonomy that encompasses all of metal’s subgenres: across these subgenres, there are various stylistic differences, but the similarities often far outweigh those differences and create an aesthetic family replete with infinite differences and infinite similarities.

Perhaps at the far end of the spectrum is Christian metal, which lyrically is the most at odds with much of the rest of metal. Often however, even Christian metal is not overtly religious in lyrical content, and maintains many of the same compositional tropes of other metal subgenres.[35] 1980’s glam/heavy metal act Stryper was a well-known early Christian Metal act, achieving platinum status for their third album To Hell with the Devil, in so cementing Christian Metal as a viable subgenre. As seen with this album title, and later ones such as Murder by Pride, No More Hell to Pay, and Fallen, Stryper used tropes of metal nomenclature and applied them to their own work. Besides not being immediately evident from any of those album titles that Stryper is devoutly Christian, their look was traditionally glam and played well with audiences regardless of their faith.

Whether glam, death, Christian, or black metal, speed and volume, as well as a large amount of distortion and various other effects applied to the guitars are essential components of metal DNA. When one of these factors is altered, others remain and often in an advanced state – akin to losing one sense and the others getting better, where neural reorganization reverts unused brain capacity to enhance the remaining senses. Doom metal, typically far slower than many other forms of metal, is some of loudest metal around. Loudness (actual volume), while a facet of equipment and technical ability, can be surprisingly malleable tool in determining how dynamics are used to denote various passages and changes in compositions. In nu-metal, often the speed of conventional metal was parlayed into the use of a DJ who would “scratch” behind the rest of the band, using an element of hip-hop to reference high picking speed on a guitar. The hybridization that defined nu-metal was not excluded from being implicated in metal tradition, and across nu-metal it is easy to observe metal’s influence.

THE ROLE OF METAL IN SOCIETY (1972-1990)

In his book Sells Like Teen Spirit: Music, Youth Culture, and Social Crisis, Ryan Moore attributes the birth of heavy metal to de-industrialization and the rise of counterculture in Britain throughout the late 1970’s.[36] With deindustrialization came a subsequent loss of mechanized jobs in the economy, and widespread joblessness, and low wage earning middle class of British men, accustomed to being a provider (“breadwinner”) for their family. In the midst of this transition to a service-based economy, there was the perception that skilled labor demanded “self-presentation, emotional labor, and customer service… historically defined as ‘women’s work’.”[37] Coupled with fiercely neo-liberal policy making through Thatcherism and Conservative rule in Britain at the time, this bred a deep seed of mistrust for authority among Britain’s youth. The state was seen as merely interested in economic policy, not the daily struggles of citizens, and to many British youth this gave reason to move outside of the traditional working-class existence of many Brits.

From this mistrust and discontentedness arose the originators of heavy metal. Ozzy Osbourne was the child of a toolmaker and a factory worker, the fourth of six children. Out of this situation Osbourne managed to start one of the single most influential, original, and famous bands in the history of western music after dropping out of school at 15 to work construction jobs.[38] Ozzy is but one example that can be found throughout metal, of people who did not see a traditional education or workforce path ahead of them, and instead preferred the ideals that metal presented. Making metal music stood as a direct refutation of societal norms – it was loud, it was ugly, and the lyrical content aligned it as an uncouth art. Metal was ostensibly in this way a youth movement that ran counter to the larger youth movement of the 60’s. Much in the way that the 60’s youth movement sounded like mainstream rock of the time (Woodstock being a key cultural/musical example) in several ways, the 70’s and 80’s bore vast swaths of people that metal appealed to far more. A large reason for this was the bleakly modern conditions that early metal musicians and fans came out of, with conditions that profoundly shaped what metal looked and sounded like. By and large, theirs was restlessness with suburban and exurban spaces in Britain that in no way mirrored what the idealist images of rock and rock fans presented. This would be echoed later by nu-metal, and the architecture of wasteland suburbia that was seen throughout the United States.

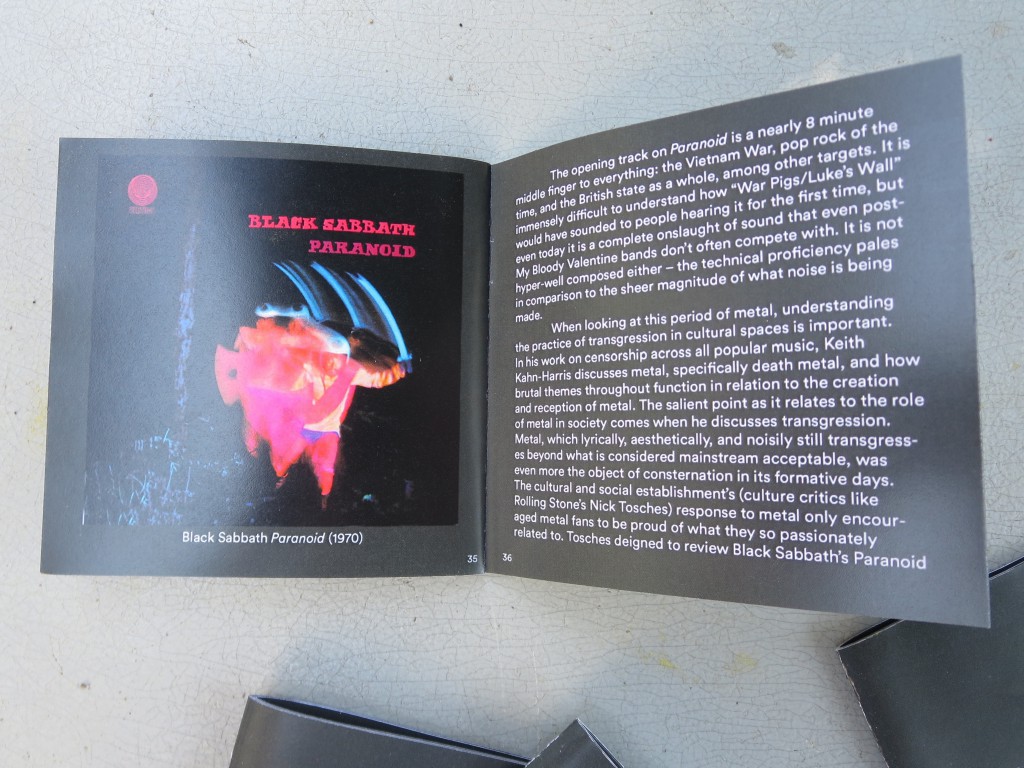

In the 1970’s Birmingham (Black Sabbath’s city of origin) was losing its status as England’s manufacturing capital in a Conservative-led effort to divert jobs to other regions in Britain and the UK. In turn, Birmingham saw some of the largest unemployment rates and job losses in the UK, and large numbers of residents struggled to get by. The state was seen as a driving force behind job loss and despair in Birmingham, and many of the aesthetic tenets of metal were seen as a direct response to this. Laura Weibe Taylor, in her piece “Images of Human-Wrought Despair and Destruction: Social Critique in British Apocalyptic and Dystopian Metal”, pushes the view that much of early heavy metal’s fascination with the occult, science fiction, and dystopia was a manner of critiquing the state. The earliest British metal bands “came from the white, male industrial working class of Birmingham, England)” displaying “militant grimness” in every dimension of their music, be it logos, staging, lyrics, or album art.[39] Looking at Black Sabbath’s second album, Paranoid has distinctively dystopic album art, and the early Led Zeppelin covers depict varying and vaguely disturbing scenes. The cover to Houses of the Holy (1973) shows faceless, female figures crawling up a terraced monolith to no certain destination.

This ‘grimness’ was an effort to confront the social malaise and spatial wasteland they grew up in. Weinstein, speaking on the origins of metal, points out that Black Sabbath’s name was sourced from a horror film, as a “corrective to the ‘peace and love’ credo that permeated the youth culture” of the late 1960’s and early 1970’s.[40] It is also fittingly metal to consider the Sabbath, a day of worship, as being “black” and hence aesthetically referential of Satanism. Following this line of thinking, it makes sense that metal sounded chaotic, and purposefully rough-hewn.

The opening track on Paranoid is a nearly 8 minute middle finger to everything: the Vietnam War, pop rock of the time, and the British state as a whole, among other targets. It is immensely difficult to understand how “War Pigs/Luke’s Wall” would have sounded to people hearing it for the first time, but even today it is a complete onslaught of sound that even post-My Bloody Valentine bands don’t often compete with. It is not hyper-well composed either – the technical proficiency pales in comparison to the sheer magnitude of what noise is being made.

When looking at this period of metal, understanding the practice of transgression in cultural spaces is important. In his work on censorship across all popular music, Keith Kahn-Harris discusses metal, specifically death metal, and how brutal themes throughout function in relation to the creation and reception of metal. The salient point as it relates to the role of metal in society comes when he discusses transgression. Metal, which lyrically, aesthetically, and noisily still transgresses beyond what is considered mainstream acceptable, was even more the object of consternation in its formative days. The cultural and social establishment’s (culture critics like Rolling Stone’s Nick Tosches) response to metal only encouraged metal fans to be proud of what they so passionately related to. Tosches deigned to review Black Sabbath’s Paranoid without mentioning the name of the band, or a single song on the album. Kahn-Harris relates that transgression “allows people to escape power and authority, if only for a time.”[41] This is an annunciation of early metal’s rejection of the state as an enterprise built for some but not all. It also falls in line with the dichotomy between metal as music of the people, and the widespread critical distaste in the first two decades of its existence. It’ll be seen that transgression is a key part of nu-metal, as it was an affront to hip-hop and metal as well as existing as a youthful cultural zeitgeist that abhorred the modern miasma of the 1990’s that had its locus in suburban mall culture.

Nu-metal’s sonic transgression was multifaceted and will be further explored later, but it is important to recognize that where people expected the heavier sound of down tuned metal, Limp Bizkit and contemporaries added a DJ, functioning as an affront to the strict guitar-orthodoxy of metal. On top of this, the succinct and often rhyme based vocal delivery of Jonathan Davis (Korn) and Fred Durst (Limp Bizkit) drew associations with the more sing-song hip-hop of the early 1990’s. Rage Against The Machine’s Zack de la Rocha directly rapped over the heavy tones of bassist Tim Commerford and the pioneering metal-turned-laser guitar tone of Tom Morello. On their 1993 single “Bombtrack”, Morello sends out squalls of riffs while de la Rocha spits verses about inequality: “Landlords and power whores/ On my people they took turns/ Dispute the suits I ignite/ And then watch ’em burn.”[42] This combination was unprecedented, even when considering the Beastie Boys and certain Red Hot Chili Peppers songs that came out prior to this.

Metal was the angry, fun, and much louder child sonically borne out of the first 15 years of rock music. However, heavy metal also initially existed in a liminal space that was not overly rock-influenced; the early Black Sabbath and Iron Maiden records, especially 1970’s Paranoid and 1980’s Iron Maiden, have little to do with the past decade of rock before them, perhaps borrowing slightly from The Who and Yes, but only in the least strict sense. This gave metal a huge cultural push, as it was seen as ontologically different from other guitar-based music and it differentiated itself as much as possible. Metal found its difference in its relentless dedication to unchanging magnitude – it refused to bend to pop sensibilities of how respectable music should be made. It turned into a commercially successful genre because of this relentlessness, and its refusal to be easily digested. Into the 1980’s, when metal subgenres began rapidly developing, metal fans across the board saw their favorite acts as profound statements of acceptance and insight to their daily lives.[43] The massive explosion of metal into the mainstream was carried by the buying power of fans who demanded to hear their favorite records on the radio, right next to more mainstream popular[44] acts at the time, like Hall and Oates, REO Speedwagon, The Steve Miller Band, among others. However, understanding this fan base is essential to understanding metal’s role in society in the US, and is essential for laying the groundwork from which nu-metal would find its massive niche.

Much of the scholarly work on metal has come in the form of ethnographic survey of metal fans, whether autobiographic or not. This is far less common when looking at other genres or styles; the work on hip-hop, rock, jazz, and blues more often focuses on musical theory or performer-based interpretation of a large body of work.[45] One result of this difference is that metal, perhaps more so than any other genre, is critically filtered through the institution of metal fandom. Across the texts surveyed in the writing of this thesis, there have been none so far that do not engage the passionate fan experience of metal. This means that metal (and eventually nu-metal) must be critically approached through both aesthetic and societal tenets to be fully understood.

In an effort to simplify a wide array of cultural factors, this survey will look to focus on three primary tenets of study. The first of these deals with the sound of nu-metal, namely what does it sound like, who originated this sound, and what does this sound tell us about the ideals the music is promoting, to the extent that it can. Secondly, a survey of socio-cultural “scene” around nu-metal – namely who was it being sold to, and why? And finally, what do subgenres, or what Mark Slobin calls “micromusics” allow us to understand about a greater system that surrounds cultural production in the United States? Using these frameworks to progress will ultimately allow a cohesive understanding of both how nu-metal became popular and what effect on American society it had.

NOTES

[17] Jennifer C. Lena, Richard A. Peterson, “Classification As Culture: Types and Trajectories Of Music Genres,” American Sociological Review 73 (2008): 697.

[18] Franco Fabbri (1981). “A Theory of Musical Genres: Two Applications,” edited by D. Horn and P. Tagg Popular Music Perspectives (1981), 1, from Göteborg and Exeter: International Association for the Study of Popular Music.

[19] Marino, Gabriele, ““What Kind of Genre Do You Think We Are?” Genre Theories, Genre Names and Classes Within Music Intermedial Ecology,” In Music, Analysis, Experience New Perspectives in Musical Semiotics, ed by Costantino Maeder et al. (Leuven, BEL: Leuven University Press, 2015) 243.

[20] Marino, ““What Kind of Genre Do You Think We Are?”, 246.

[21] Pierre Bourdieu, A Social Critique of The Judgement of Taste. Translated by Richard Nice. (Boston, MA: Harvard Press, 1984).

[22] Bourdieu, A Social Critque, 483; Weinstein, Heavy Metal; Robert Walser, Running With The Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music. (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1993).

[23] Henceforth interchangeably referred to as simply “metal”. Subgenres, such as glam metal and nu-metal (the focus of this work) will be referred to by their proper name. This per Weinstein’s use of the term “heavy metal” and subsequent shortening.

[24] Weinstein, Heavy Metal, 23.

[25] ibid.

[26] These are some of the most common names that appear in nearly every text, but specifically Weinstein, Bayer’s anthology on British heavy metal, and Robert Walser’s book speak to naming conventions in heavy metal.

[27] Joy Division was the name given to Nazi brothels in concentration camps.

[28] Overell, Affective Insensities.

[29]Weinstein, Heavy Metal, 27-30.

[30] I.e. jazz being played by people in suits, country being played by people in blue jeans, etc.

[31] There has been extensive writing about how music and fashion correlate, but Janice Miller’s book Fashion and Music (2011) does a really good job of outlining the history of their relationship.

[32] Across readings from Azzerad, Hyden, Berger, Weinstein, Moore, Klosterman, and several others, each pertains a description of metal fans using these exact terms (as well as others).

[33] Chuck Klosterman, Fargo Rock City. (New York: Scriber, 2001).

[34] Overell, Affective Insensities.

[35] Jonathan. H. Ebel, “Jesus Freak and the Junkyard Prophet: The School Assembly as Evangelical Revival,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 77 (2009), 16–54.

[36] Moore, Sells Like Teen Spirit; Weinstein, Heavy Metal.

[37] Weinstein, Heavy Metal. 80.

[38] Ozzy Osbourne, I Am Ozzy, (New York: Grand Central Publishing, 2009), 3-5.

[39] L. W. Taylor, “Images of human-wrought despair and destruction: Social critique in British apocalyptic and dystopian metal.” In Heavy Metal Music in Britain, ed. Gerd Bayer, (Farnham, England: Ashgate Publishing, 2009) 90-110.

[40] Weinstein, Heavy Metal, 35.

[41] Keith Kahn-Harris “Death Metal and the Limits of Musical Expression” in Policing Pop ed. Martin Cloonan et al. (Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2003), 85.

[42] Morello, Tom. “Bombtrack”, Rage Against the Machine. Epic Records, B00138KCC4.

[43] Weinstein, Heavy Metal, 10-15; 95-143; Chuck Klosterman refers to this phenomenon as one of the “redneck intellectual” a truly brilliant term that serves to mean someone who thinks in critical terms in a place (geographically and culturally) where “critical thinking is almost impossible”.

[44] Per the Billboard Top 100 chart.

[45] See: Lipstick Traces by Greil Marcus for rock, Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop by Jeff Chang for hip-hop.

Next: Chapter Three:

Bulls on Parade

Chapter Four:

Freak on a Leash

Chapter Five:

Change (in the House of Flies)

Acknowledgements, Bibliography, Listening Appendix