nu-metal, affective masculinities and suburban identities: guest blog by Niccolo Dante Porcello

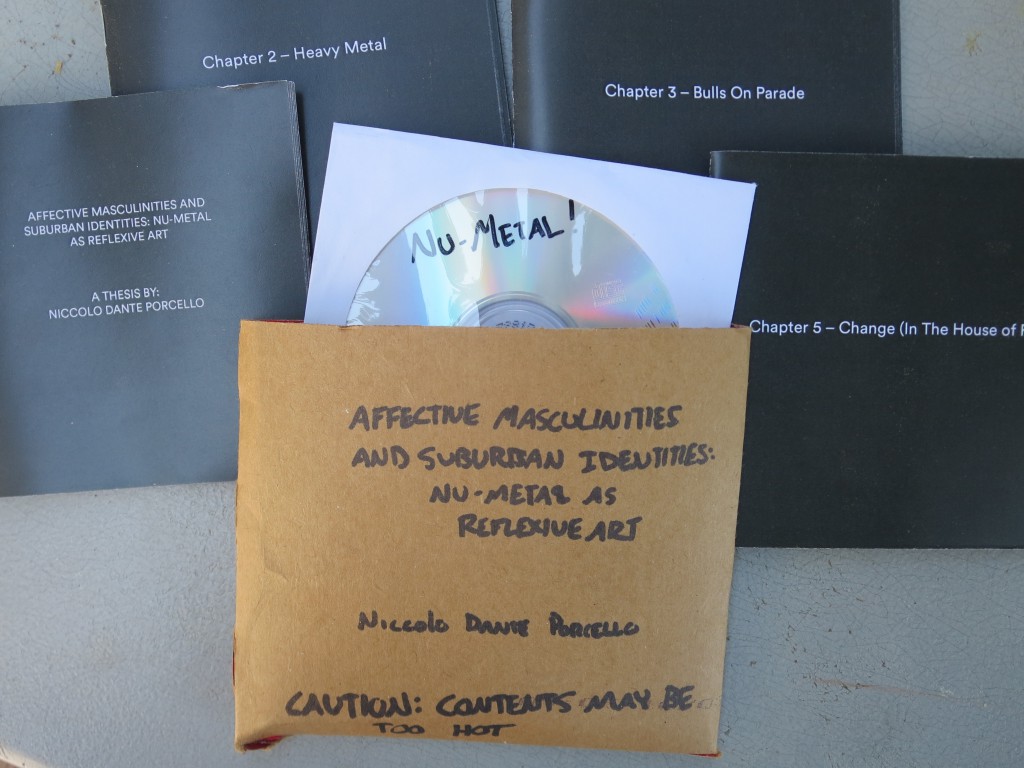

by Leonard Nevarez on Jun 2, 2016 • 2:10 pm No Comments[Here’s the second 2016 senior thesis in musical urbanism I’m pleased to share on this blog. Too young to experience nu-metal when it first came out, Niccolo Porcello produced this provocative hot-take on the 1990s subgenre and its roots in heavy metal and hip hop subculture. His other senior thesis adviser and I gave this thesis an A-, in part because Niccolo wrote this for his major in Urban Studies, and he didn’t provide a formal conceptualization of suburbia until Chapter 4. But for a display of senior-year inspiration (check out the historically accurate CD booklets he printed his thesis out on, as well as this Spotify playlist) and an insight into how smart young music listeners might sympathetically regard this bygone style of music, Niccolo’s was one of the more memorable theses I’ve ever supervised. Currently, he runs the indie label Sad Cactus Records when he’s not seeking more gainful employment. -LN]

Affective Masculinities and Suburban Identities:

Nu-Metal as Reflexive Art

A Thesis By:

Niccolo Dante Porcello

April 2016

If our work is to explain the role of music in society, then our interpretations of music must be an attempt to understand the meaning of the music for the people who participate in it. If an interpretation of a genre of music or subculture is present for the scholar and no other social actor, I cannot see how it can be consequential for the larger society.

– Harris Berger, Metal, Rock, and Jazz: Perception and the Phenomenology of Musical Experience.To many of its detractors, heavy metal embodies a shameless attack on the central values of Western civilization. But to its fans it is the greatest music ever made.

– Deena Weinstein, Heavy Metal: The Music and Its Culture.

CHAPTER ONE:

CLICK CLICK BOOM

In their 2001 song “Click Click Boom” Saliva singer Josey Scott says, “What the hell is wrong with me? / My mom and dad weren’t perfect / But still you don’t hear no cryin’ ass bitchin’ from me”, over the chug of the genre-encapsulating down tuned guitars, making one of the most self aware statements in nu-metal. Nu-metal resonated with a generation of discontented youth that considered themselves to be disenfranchised and abandoned by the cultural state of the U.S. around them, while also being given a powerful sense of individualism. What Scott is saying elucidates the confusing, often brutal, and strangely self-honest nature of nu-metal. The popularity of nu-metal ostensibly peaked in 1999 at Woodstock’s 30th anniversary, where Korn, Limp Bizkit, Rage Against The Machine, Creed, and numerous other acts played to 200,000[1] people over the course of three days in upstate New York. Two gang rapes, several overdoses, and widespread violence were frequently documented occurrences at the festival.[2] These kids, largely from the suburbs, exurbs, and rural areas, found some form of empowerment in the violence, misogyny, aggression, and party-fueled life repeated back at them through songs like Limp Bizkit’s “Nookie” and Drowning Pool’s “Bodies”.

Understanding why this music held the weight it did is a complex task and the ultimate goal of this thesis. The decade in which nu-metal was most active coincided with a number of profound changes in the way that people, especially youth audiences, consumed music and media as a whole. There was a confluence of the Internet moving into homes, online music sharing, catastrophic suburbanization, and the specter of censorship that changed the influence that nu-metal had on popular culture at the time. Additionally, the expectations of masculinity were shifting to a more emotionally capable, as well as culpable position.

In his phenomenal 10-part “Whatever Happened to Alternative Nation?” music critic and journalist Steven Hyden describes nu-metal as “music that took the sludge and the self-pity of early-’90s rock and turned it into something leaner, meaner, and nefariously empowering”.[3] The empowerment that Hyden refers to came through rejecting the aesthetics of pity; nu-metal bands made a point to mock the demonstrative, emotionally pitiful displays that much of grunge championed at the time.

As an aesthetic sub-culture, nu-metal riffed heavily on the aesthetic precursor that metal provided – long before infamous nu-metal band Slipknot was wearing masks and donning pseudo-kabuki makeup, Ozzy Osbourne was famously biting the head off a bat and being accused of worshiping Satan.[4] Metal, in most of its various forms, has been mainstream since its inception. Rosemary Overell says on metal’s sub-culture status: “metal existed right in the heart of hegemonic culture — in the suburbs — as a deviant, even resistant anomaly,”[5] and nu-metal is but one subgenre in a long lineage of metal to capture the hearts and minds of America’s predominantly teenage, middle class, buying-power heavy youth. The merchandising power, ticket and record selling ability of metal artists was almost unrivaled between 1975 and 1990 in the United States.[6]

Of metal’s many subgenres, nu-metal stands as one of the shortest-lived and most commercialized. Use of the genre description “nu-metal” began with Korn’s 1994 self-titled album and ended, in terms of significant commercial popularity, in 2004. Korn’s lead singer Jonathan Davis reportedly “detested” the genre tag nu-metal, instead preferring “fusion” to refer to the group’s hybridized sound.[7]

The lackluster sales of Korn’s album the year prior, and Limp Bizkit’s minimally selling The Unquestionable Truth (Part 1) signaled the end of nu-metal’s commercial dominance, and cultural relevance. However, in its decade long reign, bands like Godsmack, Disturbed, and Saliva were routinely selling millions of copies. Media outlets like MTV, SPIN, and Rolling Stone devoted serious amounts of time to nu-metal, and retail outlets like Best Buy and Wal-mart did exclusive album releases of nu-metal albums.[8] As a derivative of metal, and ultimately rock, nu-metal brought with it a set of influences that had proven to be commercially popular already and hybridized them with those of hip-hop. One of the first true forays into genre hybridization came from established metal act Anthrax, and up and coming hip-hop group Public Enemy. Their 1991 song “Bring The Noise” reached #56 on the Billboard chart and registered as a significant commercial success, ushering in the idea that a rap-rock hybrid was commercially possible. As early as the late 1980’s Brooklyn, NY’s Beastie Boys were beginning to test the waters of success with something akin to a rap-rock hybrid, although theirs was still firmly rooted in the early hip-hop tradition. Other acts like Suicidal Tendencies were also bordered on rap-rock territory in this time, finding varying amounts of success combining the contextual elements of rock (guitars, distortion, singing) with the more stylized lyrical delivery of hip-hop.

As Public Enemy and Anthrax worked on “Bring The Noise”, the United States was reaching the end of a decades-long crossroads, one that took a predominately white industrial workforce and shifted it to one that was highly skilled and rooted in a more intellectual tradition.[9] As a result of this, a large amount of previously heavy-laboring white communities of the U.S. experienced something akin to widespread disenfranchisement for the first time in the post-war era. At the same time, black populations were being left with the deindustrialized city, and the wastelands left behind. In her book Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America, Tricia Rose speaks to the effect of deindustrialization on black population and culture, saying: “hip-hop emerges from the deindustrialization meltdown where social alienation, prophetic imagination, and yearning intersect.”[10] Hip-hop as a medium attempted to understand and voice marginalization as a product, primarily, of white flight and the social policies that followed.[11] Nu-metal negotiated a path between these moments, although primarily representing the whiter side of this transition.

Both shifts were coupled with a transformation in the expectations of masculinity that had a profound effect on the male-produced culture that was being created. Pieces by Moore and Hyden especially illuminate the perceived threat from the end of second wave, and beginning of third wave feminism in the mid-to-late 1990’s and early 2000’s. The rhetoric of dominant masculinity was one that was increasingly being shut down and critically deconstructed through these moments. The rise of nu-metal also coincided with an industry that was commercially focused on grunge. As Hyden says so perfectly about grunge:

Grunge reminded us that, deep down, we’re all victims of a cruel and unjust world, and this vulnerability unites us; there was only one victim in the new music, and that was the listener, who was beset on all sides by abusive parents, mocking teachers, needy girlfriends, and all the uncaring and privileged kids at school, who never, ever had it as bad as you; even worse, those fucking bitches thought they were better than you.[12]

The misogyny and violence of Hyden’s description is satirical, but what he touches on comes from a place of cultural truth. In the same piece, he goes on to discuss the time he wrote a scathing review of a Korn concert for the regional paper, and soon began to receive hate mail from all over the country. Hyden collected all of the hate mail into a booklet he titled “Dear Faggot”, saying that was “the most common salutation I received from Korn fans.”[13]

The guiding principal for this thesis can be taken from Harris Berger’s assertion that:

if our work is to explain the role of music in society, then our interpretations of music must be an attempt to understand the meaning of the music for the people who participate in it. If an interpretation of a genre of music or subculture is present for the scholar and no other social actor, I cannot see how it can be consequential for the larger society.[14]

By using this ideology to approach nu-metal, we can attempt to understand the cultural, societal, and chronological conditions that instigated some of the most divisive, gender-specific, and lucrative culture in post-war America. The sheer male domination of nu-metal, coupled with the targeted manifestations of its commercial marketing and the propagation of its highly dedicated suburban fan-base was a unique turn of events. Nu-metal also was one of the first examples of a pop cultural desegregation that has only intensified since it burst onto the scene, pairing white and black music.

Any answer will come from a multifaceted approach encompassing urban studies, media studies, American studies, and additional interdisciplinary canons that shed light on the innumerably complex system of American life and culture. In facing nu-metal a decade removed there is the alluring sense of the present that still lingers, but also the scholarly distance to critically understand some of the potential fallout both as it pertains to the music industry, and what Harvey calls the “socially destructive”[15] architecture of sprawl and the suburbs. This thesis is a cultural sociology in the sense that Weinstein[16] considers, namely: a thorough investigation of the creation, appreciation, and celebration of nu-metal, in addition to a survey of the audience, and literal mediators (Korn TV, SPIN, Rolling Stone) that paved the way for a cultural phenomenon.

NOTES

[1] Alona Wartofsky. “Woodstock ’99 goes up in smoke,” Washington Post, July 27, 1999. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/national/daily/july99/woodstock27.htm

[2] Rob Sheffield. “Woodstock ’99: Rage Against The Latrine”, Rolling Stone, Sept 2, 1999. http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/woodstock-99-rage-against-the-latrine-19990902?page=2; Warofsky, “Woodstock ‘99”, Washington Post.

[3] Steven Hyden, “You’re Either With Korn and Limp Bizkit, or you’re against them,” AV Club, February 8, 2011, http://www.avclub.com/article/part-9-1998-youre-either-with-korn-and-limp-bizkit-51471

[4] Helen Farley. (2009). “Demons, Devils and Witches: The Occult In Heavy Metal Music,” in Heavy Metal Music in Britain, ed by Gerd Bayer. (Farnham, England: Ashgate Publishing, 2009), 73-85.

[5] Rosemary Overell, Affective Insensities In Extreme Music Scenes: Cases from Australia and Japan. (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014.)

[6] For example Kiss, one of the earliest glam metal bands, has recorded around 215 studio songs over the course of 19 albums. In comparison, there have been over 3,000 different products with the Kiss logo attached – nearly 14 different commercial products for every Kiss song.

[7] Jonathan Pieslak, “Text and Identity in Korn’s ‘Hey Daddy’”, Popular Music 27 (2008): 36.

[8] Korn was one of the most prominent and successful bands at utilizing these commercial tools.

[9] Ryan Moore, Sells Like Teen Spirit: Music, Youth Culture, and Social Crisis. (New York: NYU Press, 2010).

[10] Tricia Rose, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America. (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1994). p. 21.

[11] Jay Chang in his book Can’t Stop Won’t Stop and Tricia Rose both agree on this point.

[12] Steven Hyden, “You’re Either With Korn and Limp Bizkit, or you’re against them,” AV Club, February 8, 2011, http://www.avclub.com/article/part-9-1998-youre-either-with-korn-and-limp-bizkit-51471

[13] ibid.

[14] Harris Berger, Metal, Rock, and Jazz: Perception and The Phenomenology Of Musical Experience. (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1999).

[15] Dolores Hayden, A Field Guide to Sprawl. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004).

[16] Deena Weinstein, Heavy Metal: The Music and Its Culture. (Boston, MA: De Capo Press, 2000).

Chapter Three:

Bulls on Parade

Chapter Four:

Freak on a Leash

Chapter Five:

Change (in the House of Flies)

Acknowledgements, Bibliography, Listening Appendix