[Update: this blog post has been expanded and revised into an article for the Journal of Popular Music Studies.]

I’m always puzzled when I hear how Elvis Presley or Mick Jagger “sounded black” when they first appeared on the radio. Back in the 70s, when I was a kid listening commercial radio that played pop, soul, and disco music, I never once mistook the vocals of Presley and Jagger as coming from African-American singers. Perhaps this was because these pop icons had been on TV and magazines for more than a decade when I first became familiar with their music. Perhaps.

But even today, after I’ve gotten better at identifying the many strands of popular music and sequencing their historical influences upon later music, I still don’t hear their voices as black. Yes, it’s clear now how the attack of their performance, the grit in their voice, and the slur of their vowels show the influence of blues and R&B singers before them—artists who weren’t recognized by mainstream white pop music audiences back then. And yes, their historical significance is in some part due to the fact that they introduced African-American music to white audiences (whether or not that was cultural exploitation, go ask Public Enemy). But that’s just it: Presley and Jagger sounded black to listeners who had no historically available vocabulary to interpret the social and cultural transgressions set off by the singers’ vocals, performance, artistic choices and careers other than the discourse of race at the time. Hence, they “sounded black.”

The larger point here is a basic one in cultural anthropology: meaning doesn’t emerge immediately out of language—or of any symbolic system, visual, aural (most relevant here) or otherwise. Instead, people attribute meaning to the vocabularies and grammars of language by collectively assigning referents, at the most basic level, in terms of binaries or contrasts. “Hot” makes sense only in reference to a symbolic opposite, “cold”, and “white” only by contrast to “black.” In this way, symbolic systems aren’t transcendent; rather, they’re collective accomplishments that emerge through the play of history, its changing social contexts, and the symbolic codes and tools that mediate language to its users.

So what does it mean when we hear that music sounds like a city?

Joy Division’s Mancunian myth

Joy Division offers as good a case study as any to break down the myths we revel in when we say a particular band or music “sounds like” a particular place. Most serious music fans today can associate Joy Division with the northern English city of Manchester. Some will appreciate Joy Division’s historic distinction as the first truly important Mancunian band to break out in Manchester, bypassing the centrality of London and its music companies, recording studios, and entertainment media. Many more fans will know that a string of legendary bands (New Order, the Smiths, Happy Mondays, the Stone Roses, that whole “Madchester” scene, Oasis) followed upon the DIY/”made in Manchester” tradition that Joy Division pioneered. And a remarkably extensive literature and filmography portraying the band in its moment (three feature-length films?!) have helped spread the idea that the group’s aloof, reticient, yet undeterred stance somehow captures a quintessence of the Manchester ethos—at least before the drug ecstasy turned the city into the UK’s manic dance capital for a time.

But Joy Division is often assigned a deeper aesthetic relationship to Manchester than just these social-historic characterizations. For many listeners, Joy Division sounds like Manchester. That is to say, their music doesn’t just come from the late 1970s Manchester of deindustrialization, a carceral welfare state epitomized by concrete housing estates built in brutalist architecture style, Margaret Thatcher’s subsequent class warfare upon Britain’s industrial proletariat, and the discovery of expressive and artistic possibilities in the wake of punk—their music recreates and conveys this historic milieu through its sonics and aesthetics. From Grant Gee’s 2007 documentary Joy Division (all quotes in this essay come from this source unless otherwise noted):

Liz Naylor: When Unknown Pleasures came out, it was sort of like, This is the ambient music for my environment. I mean, when I think about Joy Division, they’re an ambient band, almost. You don’t see them function as a band. It’s just the noise around where you are.

Paul Morley: It was almost like a science-fiction interpretation of Manchester. You could recognize the landscape and the mindscape and the soundscape as being Manchester. It was extraordinary that they managed to make Manchester international, if you like—make Manchester cosmic.

Jon Wozencraft: Unknown Pleasures is also a very iPodded kind of world. It’s urban, but it’s not. It’s about a landscape, but that landscape is primarily an interior landscape. And so, what is very, very important about it now is to see where we’ve travelled from since then and exactly why it still sounds so bloody contemporary.

These statements, like so many others issues by writers and fans alike, erudite and thick, constitute a pervasive myth about Joy Division’s relationship to late 1970s Manchester. The myth goes that through its music, Joy Division manifests and summons a historic urbanism with uncanny fidelity; like vinyl grooves reproducing soundwaves from a bygone time and place for eternity, audiences can seemingly revisit the Manchester of that era just by listening to the recordings. This would be a remarkable feat, considering that singer Ian Curtis never made lyrical or vocal reference to the city, specific landmarks or groups, or really any concrete references to ways of life. Such is the remarkable power of Joy Division’s music and—let’s give credit where it’s due—the echoey, disembodied production of Factory Records house producer Martin Hannett, that audiences today almost can’t help but come away from the recordings and videos with a visceral sense of alienation and withdrawal that Mancunians from that era could recognize as indigenous.

To call these aesthetic associations between music and place myth isn’t to diminish the artistry of Joy Division and their collaborators, nor to shatter the sense of emotional ‘truth’ and personal resonance that audiences can take away when listening or watching the band. However, calling it myth troubles the pleasant delusion that music as symbolic/aesthetic system can immediately record history. The sense of time-place recognition that audiences experience is a social construction; at least hypothetically, we can understand in terms of a chronological sequence of social contexts and symbolic interventions that mediate the music to its audiences so that they can competently and consciously experience a sense of time-place recognition—before they can “hear” Manchester in the music of Joy Division.

It would be impossible to innumerate the many possible social contexts and symbolic interventions that mediate audience’s different understandings of Joy Division’s Mancunian myth. But I think we can identify some of the key ones to appreciate what the kind of analysis I have in mind can look like.

Britain’s cultural geography

Before punk and post-punk emerged, England was an industrial country for almost two centuries. Its geographic imaginary was deeply impressed by the legacy of politics, trade, and finance concentrated in London, industry established in Manchester and other northern cities, and agriculture relegated to the remaining countryside. Where the production of British culture was concerned (let’s leave the culture associated with British “heritage” aside for the moment), London was the only place to be, and artists from anywhere else would have to make their move to London if they didn’t want to be regarded with disdain as hicks from the hinterlands.

This was the cultural geography that British pop music inherited. The Merseybeat didn’t escape the centrality of London, as the Beatles and their machinery quickly left Liverpool for London—a distance of just over 200 miles, but almost a different country entirely where British regional identity is concerned. Even punk initially reinforced London’s centrality in British pop music. The list of first-generation punk groups who signed with big labels out of London is long, and it includes the Buzzcocks, Manchester’s most significant band before Joy Division. As Simon Reynolds observes in Rip It Up and Start Again: Post Punk 1978-1984, the DIY ethic commonly attributed to punk really took hold only with post-punk, and Joy Division’s relationship to Factory Records in Manchester was a big part of the story. But we get ahead of ourselves.

One consequence was the relative poverty of urban/regional symbolism outside the of London orbit in British pop music. There would be references to other places, of course; think of Sheffield Steel (a Joe Cocker album) or the association of heavy metal and the British midlands. But look deeper into such music at the time—for instance, look at the lyrics—and you’ll find very little substance in these regards. British folk music might seize the moral high ground where reverence and place-specificity for the British countryside is concerned, but in pop music, images of dreary factories or drab towns were largely fodder for Londoners’ imaginations.

The state of British media

At least one might hold this perception if the British music press of the time was to be read literally. The parochialism and snobbery it displayed toward music and musicians based out of London were probably, at least in part, instincts inherited from the legacy of Britain’s geographic imaginary. However, the fairly late development of serious music journalism also has to be considered.

As Paul Gorman’s In Their Own Write: Adventures in the Music Press suggests, Britain’s music weeklies had only developed a narrative function beyond simple publicity in the early 1970s, inheriting the generational/countercultural voice from underground weeklies of the late 60s like International Times and Oz and, later, American publications like Creem and Who Put the Bomp. A journalistic focus on not just music but its surrounding culture was especially the hallmark of the NME. Melody Maker, its second-place rival in the late 70s, was slow to shift out of its reverent muso orientation, although the arrival of punk helped bring about this journalistic mission. While punk bands sprung up across the isles, the press had yet to give proper attention to their cultural/urban specificity. This was the media environment in which Joy Division appeared.

Consider as well the lack of television devoted to punk and postpunk music. Joy Division never appeared on Top of the Pops; its televised performances were so rare as to constitute key moments in pop music history. Many people vividly remember when they saw Joy Division play on Tony Wilson’s So It Goes, or do two performances of “She’s Lost Control” two months apart in 1979; such reminiscences are an important motif in the writing and films that posthumously surrounded the band.

Why does all this matter? In the relatively impoverished media environment of the late 1970s, Joy Division’s debut album would for most listeners appear with almost no aesthetic precedent or artistic context to give it meaning. Yet such was its sonic innovation and artistic power that listeners, writers, and music industry would feverishly try to make sense of it. Hence the many comparisons to Bowie and krautrock, references that get the listener close but, I think, don’t really do justice to the strange new sounds that Joy Division created. Some three decades later, the band’s closest collaborators and earliest supporters still strain to find the words for this unprecedented music:

Peter Saville [talking about designing the cover of Unknown Pleasures independent of the band’s input]: Hadn’t heard the music. They’d given me the elements; the wave patterns are astonishing. I mean, what an amazing image for something called Unknown Pleasures. I took it to Rob’s house, took the artwork to Rob’s, and he said, “I have a test pressing. Do you want to listen to it?” I didn’t know if I could sit through 40 minutes of Joy Division… especially in front of their manager [chuckles]. But I couldn’t really say no. And within moments, I knew that I had a part in a kind of life-changing experience. Minute after minute was beyond anything I could have expected. It was just beyond… it was astonishing.

Paul Morley: And just as soon as [Unknown Pleasures] started, and the drums sounded like no drums had ever sounded, and everything seemed to belong in its own space, and not quite connecting somehow, something amazing had happened.

Thus the project of making Joy Division sound like Manchester began in earnest—a project that arguably the four musicians had no major role in after providing the affecting, ambiguous source material. Here we have to look instead to the assemblage of other elements and other actors besides the group to see how the Mancunian myth develops.

Images

For an obvious starter, the visuals and graphics associated with the band helped establish their association with the sound of Manchester. In January 1979, before Joy Division had released a full-length album, NME photographer Kevin Cummins shot the group for their first cover story against a desolate daytime backdrop of deteriorating buildings and ominous housing projects (this work is now collected in a rather expensive coffeetable book of Cummins’ photography, also called Joy Division). Cummins describes how his famous shot of the band on the Epping Walk Bridge came about:

Kevin Cummins: Already by then I’ve shot two-thirds of a roll of film, and I’m conscious of the fact that I didn’t really think I had anything. I’m walking up the bridge, and they’re waiting for me, and I just felt it looked so bleak, and they were so un-rock and roll-like, that I took two frames and then took an upright shot of the same thing, and that’s all I did of that picture. And that’s I guess become probably the most recognized Joy Division image.

By November of that year, Anton Corbijn’s shoot for the NME added to the band’s visual repertoire with a photo (later used for Paul Morley’s book cover) of the band in a tunnel: three members calmly gaze away, hands in pockets, while Curtis acknowledges the camera—with uncertainty, anguish, resignation? All of these iconic images are black and white, and I suspect many viewers would assume, it being punk rock and not London flash, that these were candid photos capturing the member’s natural demeanors in their everyday habitats.

Between Cummins’ and Corbijn’s shoots, of course, Joy Division released their debut album. Never mind the effect of the music contained within the sleeve—almost immediately the album cover became a classic.

Paul Morley: And I just remember the whole… the sleeve, you know. It was just an uncanny moment, because it did belong in your collection next to Roxy Music, next to Velvet [Underground], and it didn’t look wrong next to Diamond Dogs. It was a great piece of work, but it didn’t borrow any of that language; it didn’t borrow any of that visual language. It was totally itself, and I couldn’t work out how or where it had come from.

Is it too much to argue that the juxtaposition between the naturalistic band photography and the sci-fi album cover create the symbolic poles between which Joy Division’s urbanism is imagined? The contrast between the two forms in terms of visual grammar and referents is great, but significantly both effectively convey a sense of space, albeit an eerily desolate or (in the album cover’s case) unreal version of a human landscape. Certainly the juxtaposition of the two conveys that “interior landscape” that Jon Wozencraft invoked to describe the music.

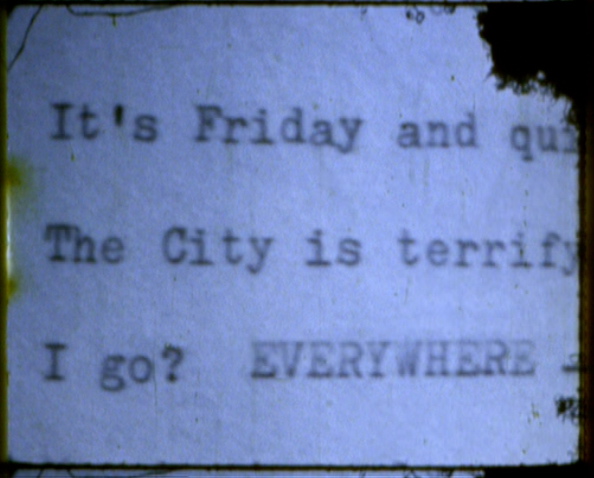

In any case, the visuals establish a resonant yet ambiguous visual grammar. Additional visual connections between Joy Division and Manchester urbanism would be made by adventurous aesthetes, most notably DIY filmmaker Charles Salem, whose 1979 short film No City Fun explicitly juxtaposed Unknown Pleasures to Manchester landscapes and Liz Naylor’s text about Manchester (it ended up on Factory Records’ release FAC 9: The Factory Flick). But for most audiences, it would take a journalistic narration to articulate Joy Division’s Mancunian myth.

Narrations

Like few other bands of the post-punk era, Joy Division attracted a zealous breed of journalists and other writers prone to remarkably purple prose when describing the band. In one category, academic writers interpreted the band’s artistry via esoteric, obtuse theorists like Martin Heidegger or Georges Bataille. (I still can’t wade through Jean-Pierre Turmel’s 1979 essay accompanying the “Atmosphere”/”Dead Souls” single.)

More influentially, Joy Division attracted hotshot music journalists who came of age with punk, most famously Paul Morley in the NME and Jon Savage in Melody Maker. Like few others, Morley and Savage used their pulpit to advocate for the aesthetic liberation that punk created—i.e., what we now call post-punk—against the “social realism” (to use Savage’s term) of oi, anarchist punk, and other unimaginative proletarian agit-pop in the wake of the Sex Pistols. Hardly doctrinaire Marxists, these writers were nonetheless sociological in their writing, looking carefully for the influence of industrial-urban-political context on music.

In Joy Division, Morley and Savage found their muse. For one thing, they had to discover Joy Division, traveling to Manchester to interview the band and its collaborators and to see the environs for themselves. No doubt this wasn’t a simple assignment for London-based journalists, and years later their writing still betrays a sense of personal investment and commitment to the city (Savage eventually relocated to Manchester in 1979).

Paul Morley: There was the Manchester damp and the shadows and omens called into dread being by the hills and moors that lurked at the edge of their vision. It wasn’t soft, where they lived. It was stained green and unpleasant. It seemed to be at the edge of the world. You had to dream your way out of such a tranquilised, inert stretch of land/mindscape. You had to use your imagination to believe that there was anything else than nothing else. In these slow suburbs, your mind would ache for release. And so would your body (1997 liner notes of Joy Division Heart and Soul box set; reprinted later in Morley’s Joy Division: Piece by Piece, pp. 239-40).

Jon Savage: I’d just moved to Manchester the spring [sic], and ‘Unknown Pleasures’ helped me orient around the city. I reviewed it for Melody Maker in typically over-heated style: “Joy Division’s spatial circular themes and Martin Hannett’s shiny, waking dream production gloss are one perfect reflection of Manchester’s dark spaces and empty places: endless sodium lights and semis seen from a speeding car, vacant industrial sites—the endless detritus of the 19th century—seen gaping like teeth from an orange bus…” (1994 liner notes of Joy Division Heart and Soul box set)

Perhaps any Londoner would come away from 1979 Manchester with the same astonishment that Savage recalled in a 2008 article (“The Things That Aren’t There Anymore”): “a disturbing new landscape that, like the city itself, the music and its people, triggered an almost overwhelming emotional response”. But few worked to cement the link between urbanization (deindustrialization, urban decline and social-political neglect), urbanism (alienation but also DIY resourcefulness against a northern English character), and sonics like Morley and Savage did. The mode of inquiry and style of writing may have come naturally to them, but against a journalistic tradition of London-centrism, disdain for the provinces, and latching on to the next big thing, we shouldn’t overlook how Morley and Savage were journalistic entrepreneurs of Joy Division’s Mancunian myth.

Contexts for listening

The elements of the Mancunian myth—an evocation of an alienated subjectivity shaped by the industrial-urban contexts of Manchester—were now present. They only awaited a deep meditation by the listener. How did Joy Division stimulate such close, attentive listening?

Not to dispense of the intrinsic mystery and beauty of the group’s music, but I think we might also recall how someone would get to hear Joy Division in 1979. A lucky few in Britain and West Europe might see the group in concert, thereby viewing them in a context removed from Mancunian associations. However, most listeners had only their recorded output to turn to. Originally, this would have been on vinyl only, a medium that fixes the listener in a stationary relationship with a record player. Radio might liberate the listener from this environment, although we shouldn’t overstate how often Joy Division was broadcast (John Peel notwithstanding) before Ian Curtis’s death. Otherwise, a spatially contained listening experience would have been typical, most likely in the domestic space of the bedroom or other rooms where the stereo would be located. For a multimedia experience, the listener might also gaze at the record sleeve or simultaneously read an article about the band.

Think about how this might reinforce the solitary, solipsistic experience of Joy Division’s music. In extended listening sessions, the mind might retreat from its psychedelic activity (no drugs required) and seek to an object or theme to alight upon. Here the Mancunian associations provided by the photography and journalism of the band might offer fertile ground for mental recreation. Having been prompted about the band’s place of origins, the listener can hardly resist imagining the landscapes that the music conveys. Correspondences between real place (Manchester), artistic consciousness (“what the band must have felt”) and aesthetic response (the “interior landscapes” that listeners inhabit) have time to develop.

How Joy Division shaped the way we listen to cities

Put together, these social contexts and symbolic interventions provide a formula for a reverent listening that Joy Division rewards with powerful emotional responses and a lasting imagination of the place, time and mindset that the group occupied. If this sounds like just another word for fan devotion, I hope the preceding argument makes clear how these social contexts—of complete geographic and cultural centralization of music industry/press in London, and of a stationary mode of listening—no longer quite exist anymore, and how the symbolic interventions of graphics, photography and journalists that Joy Division attracted are by now quite rote.

If nowadays we can access through many other bands and styles of music the “forgotten city” urbanism of geographical marginalization and expressive alienation characterized by Joy Division’s Mancunian myth, this is an achievement of many people, not just the band themselves, in the historical moment surrounding Joy Division’s brief existence. We simply didn’t listen to cities in that way before Joy Division. Now, in a very different world, we can do it all the time.

2 comments

Orla says:

Jan 20, 2014

This is great info and really interesting opinions conveyed here. I was just wondering, where are the photographs from and how took/edited them? I am completing an art project soon and would find it interesting to find an artist copy as an assignment.

Thank you.

Leonard Nevarez says:

Jan 20, 2014

The photos here are screen shots from Grant Gee’s documentary “Joy Division,” except for the Hulme Bridge photo (by Kevin Cummins) and the Paul Morley book cover (with photo by Anton Corbijn).