As someone who’s been seeking out underground rock music for over 25 years, punk rock really fucked me up. Specifically, the punk rock dogma I internalized by reading the English music weekly New Musical Express religiously between 1983-85. Punk rock in England was largely over in these years, unless you were talking about groups like Crass or Discharge, which the NME almost never did. It was more likely to cover the “hardcore” scene coming out of America, by which it meant Black Flag and Husker Du but also Swans (?) and Sonic Youth (?!). Still, in dozens of articles about the Fall, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Cabaret Voltaire, the Jesus and Mary Chain, and so on, the punk rock commandments passed down to the post-punk generation came through loud and clear:

- punk rock destroys bloated rock dinosaurs and pop stars

- guitar solos and ten-minute overtures are for public school toffs

- punk rockers hate long-haired hippies and their music

- 50s rock’n’roll and 60s R&B are the only old music worth paying attention to

- no 70s music before punk rock is any good—reggae excepted

Not that these statements weren’t true in many regards, but the burning-bridges aesthetic that places the Sex Pistols at Year One for music of any worth (i.e., music that the NME wrote about) erased any sense of historical context or cultural precedent for punk rock for me. Over the last 10-15 years, I’ve filled in the blanks with music criticism, music history, and the tidal wave of reissued albums featuring the bands and sounds that came before punk. Periodicals like Mojo and Arthur have also contributed valiantly, as have prolific archivists like Julian Cope (who has tirelessly and breathlessly documented the underground in Germany, Japan, even Denmark). Nevertheless, I still get a shock whenever I discover bygone scenes with fully developed aesthetics that are underground in the way that punk rock is, but which aren’t “punk rock.”

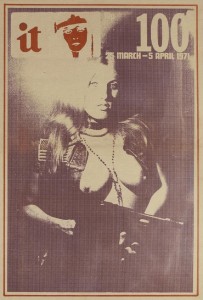

Currently I’m fascinated with the west London neighborhood of Ladbroke Grove. Its countercultural cachet today comes largely via its association with the Portobello Road Market, which runs on the parallel street, and the annual Notting Hill Carnival. But in the late 60s and 70s Ladbroke Grove was the main enclave for Britain’s drug-gobbling freaks (please, don’t call us hippies). The comparison to San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury has been made more than once, but the imminent explosion of punk rock all around London, particularly west London, casts the cultural impact of Ladbroke Grove in a more radical light. The neighborhood was the base for countercultural journals like International Times and Oz, and even a UK chapter of White Panther Party. Needless to say, bands from Ladbroke grove waved the freak flag particularly high.

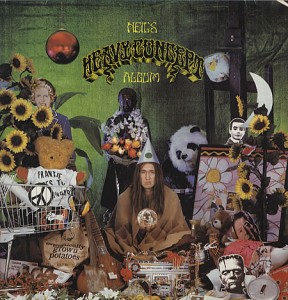

Probably the first freak band was the Deviants, who symbolized a new radical faction in London’s psychedelic underground. Their 1967 debut Ptooff was a key album, a jarring, in-your-face break with the village-green whimsy of Syd Barrett-era Pink Floyd and other, more prominent psychedelic groups from Britain. “For those who were ready to live in squats, fight policemen and radically alter their lives, music was important more for its message than its artistic qualities,” recounted Joe Boyd in White Bicycles: Making Music in the 1960s. “Leading the radical faction was Mick Farren,” the Deviants’ frontman and today a prolific writer/journalist.

The Pretty Things started a couple years earlier as one of the many UK bands inspired by the blues (the “uglier cousins of the Rolling Stones,” the press called them) before developing a more epic, psychedelic style. Critical consensus deems their 1968 album S.F. Sorrow the band’s classic; on this album, they enlisted Twink, drummer from the hard-hitting R&B band Tomorrow, who then joined…

… the Pink Fairies. A self-styled British counterpart to the MC5, the Fairies played a grizzled boogie that hasn’t aged very well but has its undeniable charms. They were one of Ladbroke Grove’s cherished “community bands” or “people’s bands,” playing free concerts in the street or outside major rock festivals like Glastonbury. Larry Wallis, their last frontman, went on to join the first version of Motörhead with Lemmy, after he was kicked out of…

… Hawkwind. The other “people’s band,” Hawkwind are undoubtedly the most famous group to come from Ladbroke Grove. They were fluent in a number of post-60s psychedelic styles, from free-form freakouts to the-snot-has-caked-upon-my-pants acoustic odes to elves-and-warlords sci-fi/fantasy tales (particularly when writers Michael Moorcock and Robert Calvert joined the band). It’s their driving, droning proto-metal, however, that has secured Hawkwind’s legend, providing the template (and the titular song) for Lemmy’s next band Motörhead as well.

I’d be the first to admit my cluelessness on the subject, which is why Rich Deakin’s Keep it Together! Cosmic Boogie with the Deviants and the Pink Fairies is at the top of my reading list, but it seems the influence of the Ladbroke Grove underground on punk rock has only recently been acknowledged. Punk’s exclusion of long-haired hippies from the domain of radical cultural and political revolt is still tenacious, informing the aesthetic common sense of music thrill-seekers from my generation. Has it taken punk rock’s final transformation into just another lifestyle brand to end its monopoly on rock’n’roll transgression and let other voices and communities from the underground be heard again?

3 comments

Ladbroke Grove Range | hazeloakeslondon says:

May 8, 2014

[…] http://pages.vassar.edu/musicalurbanism/2011/02/08/uncovering-the-underground-ladbroke-grove/ […]

Ladbroke Grove | hazeloakeslondon says:

May 9, 2014

[…] http://pages.vassar.edu/musicalurbanism/2011/02/08/uncovering-the-underground-ladbroke-grove/ […]

Shane Molloy says:

Apr 20, 2017

Read John Lydon’s autobiography and he describes in some detail his influences. Hawkwind (The Pistols opened a Finsbury Park gig in the 2000’s with a cover of silver machine) and also Krautrock (which as a genre had a huge influence on Dave Brock (Brock was part of a “rock circus” in Holland in the late 60’s)) had a huge influence on him. Lydon was much more interested in what these bands were doing in the 1970’s than 1950’s rock and roll. In fact I’d go as far as to say punk rock as a genre would probably been much wider and more diverse if Lydon was a guitarist or keyboard player as well as a vocals man. You can hear the influence in PiL. I would also say that the strict categorisation of music and youth culture pushed by the media in the 1980’s at the bequest of the authorities was largely just a political move to prevent youth movements from gathering together as they did in the 1960’s and 1970’s. It worked for about 8 or 9 years (apart from Stonehenge free festival which was brutally repressed in 1985), then acid house parties and the famous raves of the early 1990’s started attracting anybody who wanted to stay up all night on hallucinogens and / or stimulants and party hard. The punk and rock scenes looked old and tired with smack soaked grunge rock which was really just the noise and drone rock from the 80’s repackaged for the 90’s- but mighty morphing psychedelic bands like Gong with Steve Hillage and Miquette Giruardy (System 7)and Hawkwind, bringing guys like The Orb, Banco de Gaia and Eatstatic with them from the Festival scene were accepted by the ravers and Planet Dog was born. Unfortunately at the Treeworgy Tree fair and more disastrously at the Castlemorton festival dark forces led to people being poisoned and within 2 or 3 years the Criminal Justice Act was passed into Law and it became illegal to play repetitive loud electronic music outside or a to live as a New Age Traveller. Thankfully recently there has been a psychedelic rock and underground music revival – but it tends to be pretty retro and looking back to the late 60’s and early 70’s again for style and authenticity. In the early 90’s Britpop and showgaze bands toyed with re-inventing the genre (Inspiral Carpets, Ride and Slowdive were amazing), but it was either retro to gain authenticity – or seemed to lack direction and got bundled up in the rave scene or was wishy washy like the Verve. Hawkwind (You could argue they morphed into the “Dave Brock band” long ago) just released a cracking new album last year and another eagerly awaited one is due out on the 5th May in two weeks – 48 years after the first incarnation of the band. I think that Dave has worked tirelessly and has had to make hard decisions that have kept the band fresh and relevant with the fans – but keeping the sound that they are synonymous with. He has a predisposition for re-working past songs with new line-up’s as a kind of Quality Control stamp for a new line-up I think. Most of the songs are good and some are great so not so bad. Dave has such his own individual style of playing guitar – of arranging synths and oscillators – of organising a real show with lasers and dancers and poetry etc. He’s a true musical genius and, when you listen to his full output over the years you realise he covers a considerable amount of musical ground. Whatever you happen to think of the bands politics (which is pretty complex for one that started out as a “community band”) is a huge achievement and is hugely underrated. Less and less so I do hope.