Posted on behalf of Charles Wise, Library Research Department Intern

Believe it or not, the Vassar libraries are not the exclusive domains of inquiry for students but also for professors. Behind every great lecture and every written work are countless hours of researching and planning that often begin in the library. In this post, we look at how a particular member of the Vassar faculty uses the library and its resources for their work.

Robert DeMaria, Jr. is a Professor of English on the Henry Noble MacCracken Chair in the English Department here at Vassar. His interests include 17th and 18th century British literature, in particular literary scholar and critic Samuel Johnson, as well as the history of English, classics, and the book as a medium. He has published extensively on Johnson and British literature and has lectured widely in the United States and abroad.

We asked Prof. DeMaria to tell us about his research and how he uses the Vassar libraries…

You’ve published extensively on Samuel Johnson, who produced the first comprehensive lexicon of the English language in 1755. Can you tell us about your interest in him?

Samuel Johnson

I was first introduced to Johnson while pursuing my PhD at Rutgers University. I had never encountered Johnson during my undergraduate years at Amherst College nor were there any courses taught on any 18th century literature, but my dissertation director, Paul Fussell, introduced me to him and invited me to write a dissertation on literary criticism with a chapter on Johnson. The Rutgers library had a seventh edition of Johnson’s dictionary available, which I relied upon for my dissertation. When I started at Vassar, I reluctantly returned the book to the Rutgers library but luckily found a copy of the eighth edition for sale in the United Kingdom for just £50. After reading it, however, I became convinced that I had to look at the first edition of the work, so I went to Special Collections in the Vassar Library, which has a copy of the first edition.

Johnson’s dictionary is very empirical because it cites passages where other English writers used the words in addition to defining them. I became interested in these other works that Johnson used to provide context, which were often by well-known writers like Shakespeare, Locke, and Bacon. To hunt down the more obscure writers Johnson referenced, I relied heavily on Special Collections at the Vassar Library and also received an NEH (National Endowment for the Humanities) grant to go to England and use the collections at the British Library and the Bodleian Library at Oxford. In 1986, I published Johnson’s Dictionary and the Language of Learning, which investigated why Johnson chose the quotations and sources that he did. I concluded that Johnson’s dictionary was an educational work that contained many morals and principles, an important feature of any work. Since then, I’ve also published a biography of Johnson and am currently the editor of the Yale Edition of the Works of Samuel Johnson.

When researching Johnson, what resources in the Vassar library did you find most helpful to you? Are there any particular databases or archives you frequently use?

Special Collections had a lot of works by Johnson, as I previously mentioned, and they also acquired many of his works for me. Seeing the texts in their original formats brings them to life in ways that an anthology can’t, so I find looking at primary documents very valuable. I also rely on digital databases such as the Burney Collection (17th-18th century newspapers), the Oxford English Dictionary Online, the Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO), and Early English Books Online (EEBO), all of which the Vassar Library has subscriptions to. The library also has an excellent collection of reference and regular circulation works from the 17th and 18th centuries.

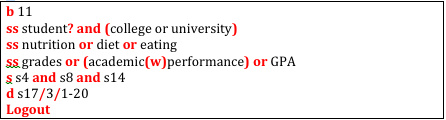

How do you approach a topic that requires extensive research? Are there any special tools or practices you rely on?

I would best describe the process as serendipitous. Just by going in and looking at a collection or an archive, you find things out that you never anticipated. For example, I was using the archives of Thomas Birch (17th-18th century British historian and biographer) in the British Library, which consist of some twenty folios of documents, and I kept noticing that a few of the letters in the archive were from servants. These were ungrammatical and non-orthographical, but I had no idea that this kind of correspondence existed. When I went back and looked through the correspondence for other major figures in other archives, however, I found even more of these letters. So research lets you discover new things you might otherwise have never known existed. Additionally, going through the Birch archive was the best way to learn about what life and literature were like on an everyday level during his life.

Tell us about some of your more recent projects.

I’m currently editing a guide to British literature from its inception to the 20th century with some of my colleagues here at Vassar, which is a four-volume work. I’ve also had Vassar students working for me through the Ford Scholars program to make the entire works of Samuel Johnson searchable online through a platform built by Yale University. This will be an unprecedented project, because it will make it possible to do things like call up the entire works of Johnson in chronological order, which has not really been possible until this project. My job was to write all of the metadata for the platform to make the works easily searchable based on specific criteria.

Is there a particular aspect of the Vassar library and its resources that you find especially useful?

I love the accessibility the library affords me to books and primary documents; it’s like having your own personal library in some ways. I especially like the Reference collection as well as the library’s collection of works from the 17th and 18th centuries and of course Special Collections. The availability of electronic databases through Vassar’s subscription is also invaluable.