We’re ringing out Women’s History Month by remembering Katharine Bement Davis, Vassar College class of 1892. Davis (1860-1935) is one of the more enigmatic women of the progressive era. She was both hailed as a reformer and reviled as an oppressor. Known for her radical advocacy for housing reform in the 1890s (as a settlement worker in Philadelphia, she once smashed all the windows of a condemned building to protest the city’s sluggishness in tearing it down), her advocacy for “fallen women,” her work for desegregation, and her vocal opposition to the death penalty, at the end of her career she aligned with eugenicists and campaigned for Herbert Hoover. Single her whole life, she wrote articles and did studies about why the marriage rate for college educated women was falling.

Davis became a student at Vassar at the age of 30, after teaching public school for 10 years, and graduated two years later with honors. The imprint of Professor Lucy Maynard Salmon on her early career, and of Vassar trustee and alumna Ellen Swallow Richards on her later pursuits, is clear. After graduation, she continued to teach, did graduate work at Columbia University, designed the New York State exhibit of “A Workman’s Home” for the Chicago World’s Fair, and worked as head resident of a settlement house in Philadelphia. One of the first women to earn her PhD at the University of Chicago, Davis left academia (as did many early women PhDs due to employment discrimination) to direct the newly opened Reformatory for Women at Bedford Hills in New York.

In 1914 she was appointed as Commissioner of Corrections for New York City, becoming the first woman to head a major municipal agency. In this role, she was identified by many fellow progressives as an agent of the establishment and the enemy. Margaret Sanger wrote in 1914, “Katharine Davis is the woman of the past and Rebecca Edelsohn [anarchist and labor activist who went on hunger strike while in jail] is the woman of the future. […] Katharine is a staunch defender of the present society, despite her experiences among ‘the fallen’ and her knowledge that poverty and destitution has driven them to prostitution.”

In 1914 she was appointed as Commissioner of Corrections for New York City, becoming the first woman to head a major municipal agency. In this role, she was identified by many fellow progressives as an agent of the establishment and the enemy. Margaret Sanger wrote in 1914, “Katharine Davis is the woman of the past and Rebecca Edelsohn [anarchist and labor activist who went on hunger strike while in jail] is the woman of the future. […] Katharine is a staunch defender of the present society, despite her experiences among ‘the fallen’ and her knowledge that poverty and destitution has driven them to prostitution.”

July 13, 1914 NYT headline describing Davis’ handling of an uprising at the Blackwell’s Island Prison

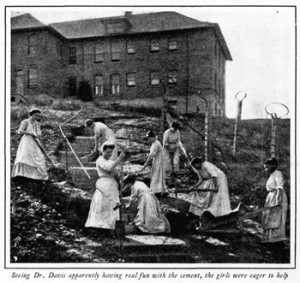

As director of Bedford Correctional, Davis had transformed a dead end, dehumanizing institution to emphasize education and vocational training because she was convinced that lack of opportunity was the major cause of women’s criminal activity, and that prisoners should have access to fresh air and exercise. However, she was eventually held responsible for deplorable conditions in jails that were under her leadership as city commissioner, and was dismissed even though she had only been in the position for less than two years.

A forceful advocate for desegregation early in her career, Davis later became an affiliate of the eugenics movement, heading John D. Rockefeller’s Bureau of Social Hygiene from 1918-1928. After a decade of pushing the bureau to focus on the study of human sexuality as part of its mission to understand and address the causes and impact of prostitution and the public health impact of syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases, Davis succeeded in completing and publishing Factors in the Sex Life of Twenty-Two Hundred Women in 1928, shortly before retiring. This pioneering study used the rosters of women’s clubs and alumnae registries of women’s colleges to find women who would be willing to answer questionnaires on topics including extramarital sex, homosexual activity, and masturbation. In many ways, this work can be seen as a precursor to Alfred Kinsey, whose first major study was not published until 20 years later, with funding from the Rockefeller Foundation.

All this, and she was valorized in her New York Times obituary for leaping into directing and organizing relief work when a 1908 vacation was interrupted by a terrible earthquake in Italy: “She aided the refugees and took charge of the situation. Palaces and municipal buildings were placed at her disposal. King Victor Emmanuel and the Pope signally honored her for her relief work. In Palermo a system of roads she established has been named for her.”

The definitive biography of Katharine Bement Davis has yet to be written, but there are many resources in the Vassar Library that could help a researcher delve into her life and career.

- The Dictionary of American Biography and Notable American Women provide the best biographical overviews available for Davis and many other pioneering women of her era. As many critics have recently noted, women are underrepresented both as editors and subjects on Wikipedia, and many of the articles on women tend to be sparse and repeat old misunderstandings and generalizations.

- Special Collections and Archives material relating to Davis includes the plan and pamphlet for the “Workingman’s Home” exhibit that was designed by Davis for the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, as well as other publications and biographical material. There is a scrapbook of newspaper articles related to Davis that is invaluable because it includes newspapers such as the NY Post and the NY Sun that, while unavailable via online sources, are crucial in understanding how Davis was portrayed in the popular media.

- Ida Tarbell (another fascinating progressive era woman) was a muckraking investigative journalist who frequently wrote about Katharine Bement Davis. Her profile of Davis that appeared in the American Magazine in December 1912, the source of the illustrations shown here, is available in print in the Periodical Room.

- Articles about Davis in the New York Times are available via the NYT Historical File, and Davis’ 1928 Harper’s Monthly article, “Why They Failed to Marry” is available via the Periodicals Archive Online.

- Estelle Freedman’s book, Their Sisters’ Keepers: Women’s Prison Reform, 1830-1930, describes the context and field that Davis was working in, and provides an excellent bibliography for further primary sources.

- The Annual Report of the Woman’s Prison Association of New York, “The Isaac T. Hopper Home” from 1916-1954, held in the Main Library, is a fantastic primary source.

- The library has several copies of Factors in Sex Life of Twenty-Two Hundred Women, and other works by Davis.

- The Journal of the American Social Hygiene Association is available full-text online through Cornell University’s terrific Home Economics Archive project.

Researching the evolving ideas around criminology is a great example of the need to experiment with search terms, especially when using primary sources such as contemporary newspapers and magazines. For example, you’ll find much more about the insidious influence of eugenic theories by using search terms such as “social hygiene” and “feeble-mindedness” than by using the word “eugenics.”

Hello! I am a student at Mary Baldwin College in Staunton VA and I am currently working on my senior thesis for my History Major and I was wondering if there is any possible way I can get access to the article links tat is from Vassar even though I am not a student there.

Thanks,

Mary Bronson