The policies aimed at Native Americans in the late 19th and early 20th century promoted cultural assimilation. Land privatization and education formed the central tenants of federal policy towards Native Americans. These policies worked to erode traditional tribal governments. The Assimilation Era was halted in 1934 when Congress passed the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA). The IRA stopped the privatization of tribal lands on every reservation, offered assistance in drafting constitutions and business charters, and implemented a revolving credit fund. Tribes electing to organize under the IRA received these benefits, but were also subject to oversight from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and tribes worried about the powers they would still hold if they chose to adopt the IRA. Once adopted, tribal governments were not able to modify their choice and remain organized under the IRA today. Non-IRA tribes were ineligible for some government programs but faced less federal oversight. This project explores the short-term and long-term differences that resulted from IRA adoption.

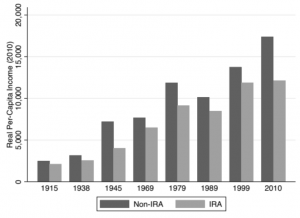

Concerns over IRA constraints proved accurate as IRA reservations consistently had a lower income per capita over time. Tribal governments organized under the IRA were limited in several ways including over all transactions for land and natural resources, which had to be approved by the Secretary of Interior and any use of the revolving credit fund was under close supervision from the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The income inequality is illustrated in the graph below. Note that the gap is largest in 1945 and 2010.

This project specifically explores the mechanisms that explain these early and persistent differences. I specifically examined four mechanisms that could be applied to parts of the IRA. They were:

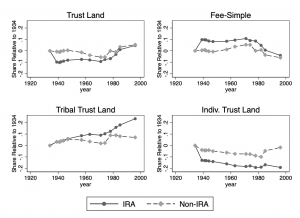

- Land Holdings: The IRA halted the allotment of tribal lands on the reservations and made funding available to return some of the private land back to the tribes themselves. To examine this data, I used BIA land reports from 1934-1996 and collected information for each land tenure type present on over 100 reservations.

The key points to highlight from this graph are the bottom left, for tribal land relative to 1934, the top left, for fee-simple land (which is essentially the type of land we live on), and the bottom right, which looks at individual trust land. The bottom left shows there was not a significant increase in the amount of tribal land returned to IRA reservations until many decades later. Similarly, the inverse of this occurred with fee-simple land, where IRA reservations saw an increase in the amount of fee simple land relative to 1934 until the 1970s. The IRA did seem to work for individual trust land, as IRA reservations saw a decrease in the amount of land shortly after implementation that persisted over time.

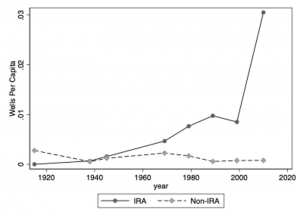

The key points to highlight from this graph are the bottom left, for tribal land relative to 1934, the top left, for fee-simple land (which is essentially the type of land we live on), and the bottom right, which looks at individual trust land. The bottom left shows there was not a significant increase in the amount of tribal land returned to IRA reservations until many decades later. Similarly, the inverse of this occurred with fee-simple land, where IRA reservations saw an increase in the amount of fee simple land relative to 1934 until the 1970s. The IRA did seem to work for individual trust land, as IRA reservations saw a decrease in the amount of land shortly after implementation that persisted over time. - Natural Resources: As an extension to the land holding changes, we examined the development of Oil and Gas wells on reservations.

The critical period in this graph is the late 1930s to 1945, as that’s when the IRA was implemented and the big income difference between IRA and Non-IRA places was not present. As the data shows, there is a fairly even number of wells per capita between both IRA and Non-IRA places in that period, so natural resources likely cannot explain the early differences between IRA and Non-IRA reservations.

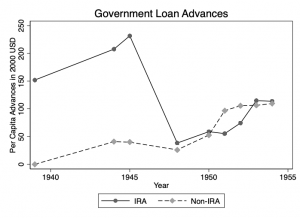

- Credit Markets: The IRA made available the revolving credit fund to reservations, so I looked to evaluate if IRA reservations were in fact given more funds to use. For this mechanismI constructed credit data from two sources: BIA Statistical Supplements from 1939-45 and BIA Annual Credit Reports from 1948-54.

This graph shows the amount of real per capita loans that were made available from 1939-54. While the IRA promised the revolving credit fund to give reservations access to funds, they failed to adequately maintain this benefit as the difference between IRA and Non-IRA locations diminished by the mid 1950s. After checking for any accounting differences, Professor Frye and I realized this may have been due to a shift in the head of the BIA in 1945.

This graph shows the amount of real per capita loans that were made available from 1939-54. While the IRA promised the revolving credit fund to give reservations access to funds, they failed to adequately maintain this benefit as the difference between IRA and Non-IRA locations diminished by the mid 1950s. After checking for any accounting differences, Professor Frye and I realized this may have been due to a shift in the head of the BIA in 1945. - Business Charters/Constitutions: The IRA promised to help ratify charters and constitutions. I looked to see if that mattered with respect to per capita income. I’m still investigating this data, but I’ve collected the constitution and charter years for many reservations and plan to evaluate if the presence of these documents influenced per capita income in a negative way.