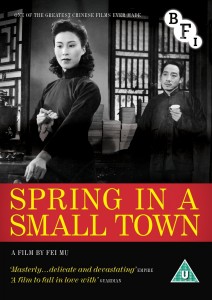

EDIT (July 10, 2015): A cut of this film that has been restored by the British Film Institute is now available!

EDIT (July 10, 2015): A cut of this film that has been restored by the British Film Institute is now available!

This is a review of Spring in a Small Town (1948), which has been hailed as the greatest Chinese film of all time. The first thing I noticed was the language. Even with my rudimentary command of Chinese, I could follow most of the dialogue even without the subtitles. This reflects the fact that the film focuses on quotidian details of everyday life: going for a walk, commenting on the weather, making a bed. But in these details is a moving story with deep significance for a Chinese audience. The film is slow-moving and subtle. One reviewer on amazon.com compared the style to that of Bergmann, but a friend of mine compared it to Yasujiro OZU (Tokyo Story (The Criterion Collection) [1953]), which I think is more appropriate.

There are only five characters in the story. Liyan is the “Young Master” of the household. He is sick with tuberculosis, and perpetually irritable. Yuwen is his wife, the narrator of the story. She is strong, beautiful, and passionate. However, she feels trapped in her existence. As she says at one point, “I do not have the courage to die, and Liyan does not have the courage to live.” The other members of the household are the one remaining servant, Lao Huang, and Liyan’s sister, who is usually referred to as Meimei. (This is really a title, “Younger Sister,” and not a name.) A fifth character soon arrives, throwing the house out of its entropy: Zhichen. He is the best friend of Liyan from childhood, but he does not realize until he arrives that Liyan’s wife is Yuwen, with whom he was in love before the war.

Anyone can enjoy the plot and performances. However, much of what makes this a truly great film will not be obvious to Western audiences, unless they are familiar with the historical context for the story. At the start of the 20th century, China made the painful transition from its last imperial dynasty to a modern government. However, soon after the government defeated the last of the warlords and established effective central control, Japan invaded, killing millions and occupying much of China. Spring in a Small Town is set right after the end of World War II. The family of Liyan was once wealthy and successful under the Qing dynasty, but the mansion he has inherited is now run down and partially destroyed from the years of warfare. Liyan always dresses in a traditional scholar’s gown, and is often seen reading books dating from the Qing dynasty. Stagnant and ill, he symbolizes China’s once-glorious past. His younger sister is young enough that she has a fresh perspective on life, and an air of vitality and innocence not shared by the other members of her household. She represents China’s potential for the future. Zhichen, the old friend, has become a doctor. He always wears Western-style clothing, and represents those Chinese of the May 4th Movement who saw China’s best hope in learning from the West. Yuwen embodies the dilemma that China faced in the early 20th century: be loyal to tradition (which, for all of its weaknesses, had its own kindness and dignity) or leave the past behind and go with the modern trends brought from the West. Finally, Lao Huang represents, I think, the masses of Chinese peasants and workers, passively waiting for someone to guide them.

The film is undoubtedly deeply symbolic, and Western viewers need some kind of entry point for understanding what it means. However, my account above is oversimplified, and makes the film seem one-dimensional when in fact it is complex and multi-layered. The characters are not cardboard cutouts (especially not Liyan, Yuwen, and Zhichen). Their emotions and the tensions they must live through are complex and feel very vivid. In the end, the film gives us not so much a pat political message as a testament to the complexity and nobility of human motivations.

The film did not stand out when it was originally released. Not surprising, given that the civil war between the Communists and Nationalists reignited after the Japanese were defeated. Then, after the Communists took control of the Mainland, a film like this could only seem decadent and bourgeois. The director, Fei Mu, died tragically young in 1951, and he was largely forgotten. It was only after the end of the Cultural Revolution and the beginning of China’s new openness to the West that the Chinese film community rediscovered Spring in a Small Town and deemed it a masterpiece. There is also a remake of it, Springtime in a Small Town (2002), which I have not had the opportunity to watch.

A few more random tidbits: (1) Notice that Fei Mu violates the “180-degree rule” in the scene where Zhichen and Yuwen talk in the study. (2) There is a website about the film here, which includes the dialogue in English, and offers translations of the two songs on the film (which do not have subtitles in my DVD). (3) Here is a link to Chinese subtitles that someone was working on. There are a lot of minor mistakes in these subtitles (it looks like a rough draft), but my DVD does not have any Chinese subtitles (unusual in more recent Chinese films). You can also find a version of the film on youtube.com that includes Chinese subtitles, Pinyin subtitles, and English subtitles. This makes the screen very busy, but is useful for language practice. (4) There are brief reviews of the film here and here. (5) Finally, one warning about the film: the quality of the print is poor. The soundtrack is also bad, sometimes cutting out at key points. (To the best of my knowledge, there is only one print of the film.) This is a film that cries out for restoration, and it is surprising that no one has raised the funds to do so yet. Nonetheless, it is well worth watching, even in this version.