Kuturbulak

December 7, 2017

Alternative Spelling: Kutur-Bulak, Kutur Bulak (Russian: Кутурбулак).

GPS Coordinates: 39°53’5’’N 66°2’55’’E (Szymczak & Gretchkina, 2000).

The following measurements were taken using Google Earth.

Elevation: 518 meters

Distance to Kattakurgan (nearest town): 19.2 km

Distance to the Samarkand city: 82.1 km

Geography and Borders

Kuturbulak is an archaeological Middle Paleolithic open-air site situated near the modern day village kishlak in the Samarkand Region of south-eastern Uzbekistan. Located south of Karadaria river that flows northwest (a tributary of the Syr Darya), the site lies in the southernmost part of the densely populated Zeravshan River valley and on the northern foothills of Utch-airy mountain where waters flow into gorges meridionally leading to formation of springs. About 19.2 km to the east of Kuturbulak situated a large town Kattakurgan. The Samarkand city, capital of the region, is situated about 80 km southeast of the site. Moreover, Zirabulak, another Middle/Upper Paleolithic site, lies about 1 km to the West of Kuturbulak (Tashkenbaev, 1975; Szymczak & Gretchkina, 2000).

Fig 1. General location of Kuturbulak (KB, annotated by the black triangle), the open-air Middle Paleolithic site in Zeravshan River valley (figure from Szymczak & Gretchkina, 2000, drawn by D. Baginska, after T. Madeyska)

Archaeology

Kuturbulak site is abundant in archaeological materials, many of which were preserved intact in the duricrust fossil layer. Two major archaeology expeditions were conducted, providing a comprehensive analysis on the Kuturbulak’s geometrical structures, stone artifacts and faunal remains. N. Kh. Tashkenbaev and R. Kh. Suleimanov first excavated the site during field seasons of 1971 and 1972. Then in 1996, archaeologists from Warsaw University and Uzbek Academy of Sciences in Samarkand, in collaboration, enlarged the excavation area and published a monograph which includes the first record of absolute dating of the site (Szymczak & Gretchkina, 2000).

Stratigraphy and Absolute Dating

The stratigraphy of the trench walls showed five distinct layers with Middle Paleolithic materials corresponding to different cultural phases, according to the interpretation of Tashkenbaev and Suleimanov. Numerous stone artifacts were found in layer I and III to V; animal bones and dark burning spots interpreted as the use of hearth were discovered in layer III. However, analysis by visiting geologists and the archaeology excavations in 1995 agreed that layer I to IV with secondary materials were disturbed and represented cultures much later than Middle Paleolithic, and only the artifacts in layer V had their original provenance. The number of cultural layers and their implications could not thus be ascertained. The hearths examined in a wider context were re-interpreted as historical ones rather than belonging to the Middle Paleolithic settlement. U/Th method dated a poorly preserved bone 85-90cm below the surface to 32.91.1 ka, while the result wasn’t reproduced and the sample might subject to geochemical processes (Szymczak & Gretchkina, 2000).

Stone Artifacts

The lithic artifacts recovered in the 1970s reached 7800 pieces, mostly made of quartz or river quartzite pebbles of different colors. Only a small percent of the assemblage was made of various flints, although natural flint materials were found in continuous layers among limestones near the site and were easily obtainable. During 1995 field season, researchers recovered 1114 stone artifacts from the trench. Due to strong evidence of secondary disturbances of the stratified layers (such as intense human activity), they divided the layers into the upper disturbed layers and lower undisturbed layers. However, even the lower layers might subject to duricrust activity caused by the variations in spring outflow. The stone artifacts were classified into flakes (with irregular retouch traces), flake cores (multiangular or of one-sided discordal shape), blades (with irregular or well-marked retouch), and other retouched tools (side-scrapers, points, end-scrapers, etc.). Only two backed knives, a characteristic type of tools of Middle Paleolithic settlement, were found in the disturbed layers. The proportion of retouched tools was remarkably high, around 41.3% in the upper layer and around 39.0% in the lower layer, while the researchers pointed out the possibility of psuedoretouching of the stone materials caused by temperature, humidity change or carbonate crystallization, as evidenced by the irregular and discontinuous traces of retouch on some of the tools. Nevertheless, a great number of retouched tools showed evidence of intense resharpening, including some heavily reduced cores and some very small flakes without any clearly defined shape. The intense and economic use of materials that produced delicate small tools, along with Kuturbulak’s location (near the mountain with abundant water resources, such as the Kuturbulak spring), indicated long-term inhabitation of the area (Vishnyatsky, 1999; Dani & Masson, 1992). Moreover, produced by lithic reduction (a dominant technology in Upper Paleolithic epoch), blade and blade tools accounted for a high proportion of the lithics inventory (16.9%). Three complete burin blades, another Upper Paleolithic characteristic tool type, were found in Kuturbulak, two of which were slim and of distinct angled form (Szymczak & Gretchkina, 2000).

Some researchers categorize the technology of Kuturbulak as the Levallois-Mousterian variant due to the great proportion of Levalloisian flake stone tools (Krakhmal, 2005), and the distinct quartzite products reflect the raw material availability in Kuturbulak rich in river pebbles (Vishnyatsky, 1999). The Mousterian culture with flake tools is usually associated with Middle Paleolithic, the epoch that marks the rise and extinction of Neanderthals who were then replaced by modern humans during the late stage. According to an unauthorized Russian website, Neanderthals who inhabited Kuturbulak were the most ancient population discovered in the Samarkand region (Mikhailovich, n.d.). On the other hand, the unbelievably high abundance of retouched tools shows a technological continuity or directional shift of lithic reduction techniques, marking a significant local evolution, the Middle Paleolithic/ Upper Paleolithic transition (Szymczak & Gretchkina, 2000; Biagi, 2008; Soffer, 2014).

Fig 2. Some stone artifacts found in Kuturbulak. Tools (1-7, 9-12, 15, 17) and cores (8,13,14,16). (Tashkenbaev & Suleimanov, 1980)

Faunal Remains

The animal bones were poorly preserved in situ and those recovered were in the form of small fragments, so only a general description of the identified faunal remains was provided. Horse (Equus caballus) was the most dominant species and accounted for almost a half of the identified bones (49.3%). Ox (Bison), wild ass, deer and elephant remains were also identified during the excavations in 1970s. The researchers then argued that remains of elephant in layer III, a species indicative of middle Pleistocene epoch in Central Asia, showed evidence that the stone artifacts were preserved in their primary provenance in the undisturbed layer. Indeed, assemblages of large mammals from various sites in Eurasia show wide distribution of elephants and even some evidence of butchering activities by human in middle Pleistocene (Pushkina, 2007; Anzidei et al., 2012). Based on the assumption that the assemblages were all in their primary position, these researchers further conjectured that the prehistoric landscape was an arid steppe land. However, the expedition team in 1995 only recovered horse remains, including a mandible fragment and some teeth, in the undisturbed layer V. Nonetheless, some researchers concluded that the prehistoric inhabitants of Kuturbulak were Neanderthals chasing after dangerous herbivores including horses and elephants (Szymczak & Gretchkina, 2000).

Conclusion

Kuturbulak is an important open-air site in the Zeravshan river valley region, in that the tool types, including Mousterian flake tools and blade flake tools, mark a technological continuity from Middle to Upper Paleolithic, and an unusually high proportion of small, heavily reduced cores shows long term inhabitation of the area, possibly by Neanderthals.

Bibliography

Anzidei, A. P., Bulgarelli, G. M., Catalano, P., Cerilli, E., Gallotti, R., Lemorini, C., . . . Santucci, E. (2012). Ongoing research at the late Middle Pleistocene site of La Polledrara di Cecanibbio (central Italy), with emphasis on human–elephant relationships. Quaternary International,255, 171-187.

Biagi, P. (2008). The Palaeolithic settlement of Sindh (Pakistan): A review. Archäologische Mitteilungen Aus Iran Und Turan, 40. 1-26.

Dani, A. & Masson, V. (1992). History of Civilizations in Central Asia. Vol. I: The Dawn of Civilization: Earliest Times to 700 BC (A. Dani, Ed.). Paris: UNESCO Publishing.

Krakhmal, K. (2005). On Studying of Historical and Cultural Processes of the Palaeolithic Epoch in Central Asia. International Journal of Central Asian Studies, 10, 119-129.

Mikhailovich, R. O. (n.d.). List of sites of primitive man. Retrieved from http://arheolog.su/kamen_vek/stoyanki/

Soffer, O. (2014). Pleistocene old world: regional perspectives. New York: Springer.

Szymczak, K., & Gretchkina, T. (2000). Kuturbulak revisited: a Middle Palaeolithic site in Zeravshan River Valley, Uzbekistan. Warsaw: Institute of Archaeology, Warsaw University.

Tashkenbaev, N. Kh. (1975). Ob issledovanii paleoliticheskoi stoyanki Kuturbulak (On the investigation of the Paleolithic site of Kuturbulak). Istoria materialnoi kultury Uzbekistana, 12, 5-15.

Tashkenbaev, N. Kh., and Suleimanov, R. Kh. (1980). Kultura drevnekamennogo veka doliny Zeravshana (The Old Stone Age Culture of the Zeravshan Valley), Tashkent.

Pushkina, D. (2007). The Pleistocene easternmost distribution in Eurasia of the species associated with the Eemian Palaeoloxodon antiquus assemblage. Mammal Review, 37(3), 224-245.

Vishnyatsky, L. (1999). The Paleolithic of Central Asia. Journal of World Prehistory, 13(1), 69-121.

Parkhai II

December 7, 2017

Coordinates

38°26’10.2″N 56°17’01.1″E (Coordinates of Kara Kala) Site is very difficult to locate on map. No coordinates nor metrics of distance from Kara Kala are reported by Khlopin.

Elevation

310m (Kara Kala)

Alternate Spellings

Parkhay II, Parhai II, Parhay II

Introduction and Geographical Description

Parkhai II is an Early Bronze Age cemetery, located along the northern edge of the Sumbar Valley in Southern Turkmenistan on the southwestern outskirts of the modern town Kara Kala (Kara Q’ala) (Khlopin 1981; Hiebert et al., 2003). The Sumbar Valley is in the westernmost area of Kopet Dag foothill region (Arkhash Region) (Hiebert, 2002). It is a minor tributary valley, which promotes the existence of vegetation in the region (Gubaev et al., 1998). Surrounded by the Kopet Dag Mountains, this area is an oasis. It is protected from the cold air from the North and the extremely dry air from the Kara Kum Desert to the East (Brummell, 2005). Parkhai II is part of a larger settlement, Parkhai-tepe, which is located 300-400m south of the graveyard (Khlopin 1981; Petrie, 2013). The main settlement has yet to be excavated (Petrie, 2013). The site is located on a hill 10m above the valley floor on a mound on the northern bank of the Sumbar River (Khlopin 1981; Hiebert, 2002). There are few alluvial deposits at the site since it is located on a hill, making the cemetery easily accessible for excavation (Hiebert et al., 2003).

Parkhai II is indirectly dated the the Early Bronze age. Excavations of the site connect Parkhai to Early and Late Bronze Age sites in the Kopet Dag foothills of Southern Turkmenistan. These Kopet Dag sites were often sedentary farming societies. Additionally, it has striking bronze objects and pottery. More extensive study of this site would aid in dating and a better understanding of what people were doing at Parkhai II.

Excavations

I.N. Khlopin and members of the Sumbar Archaeological Expedition of Leningrad Sector of the Institute of Archaeology (USSR Academy of Sciences) discovered the site in 1977 (Khlopin, 1981). The first full excavation took place in 1978. The team excavated 27 burials, 300 ceramic vessels, and various stone and bronze artifacts. It seems that the excavation by Khlopin in 1978 was the last excavation of the site since little further published information exists (Petrie, 2013).

Date

The site is indirectly dated to the Late Copper Age or Early Bronze Age in the first half to the middle of the 3rd millennium B.C. (Khlopin, 1981; Hiebert, 2002). The site has been difficult to date and no direct date has been reported. Researchers found evidence that points to two time ranges, resulting in an expansive time range (3000-2250 B.C.) for Parkhai II. This is a result of the indirect dating techniques. Initially, the site was dated closer to 3000-2500 B.C. This date was inferred by pottery found at sites in the northern foothills of the Kopet Dag, Kara-depe and Ak-depe, which seems to be imported from Parkhai II (Khlopin, 1981). Kara-depe and Ak-depe are Early Bronze Age sites (3000-2500 B.C.), placing Parkhai II in this time period (Khlopin, 1981). Khlopin provides additional evidence to date Parkhai to 3000-2500 B.C. by noting that ceremonial rites at Parkhai II are similar to those at Kara-depe, especially in the positioning of bodies (Khlopin, 1981). Finally, Khlopin dates Parkhai to the middle of the 3rd millennium B.C. (2500-2250 B.C.). Khlopin associates a lapis lazuli awl (tools used for making holes) found at Parkhai II with awls at Tureng-tepe and Ur (1981). Tureng-tepe and Ur date to the middle of the 3rd millennium, broadening the time range for Parkhai to 3000-2250 B.C (Khlopin, 1981). A direct date for this site is needed to confirm the Parkhai II date.

Finds

Parkhai II is a cemetery consisting of 450 burials; 27 burial vaults were excavated, revealing human remains, 300 vessels, and various stone and bronze objects (Khlopin, 1981). It is associated with the broad cultural area (cultural sphere) of southwestern Turkmenistan during the Early Bronze age based on burial characteristics, spiral headed pins, and pottery. Specifically, Parkhai II is linked to Kopet Dag 6 (sites: Anau II, Late Namazga II, Namazga III), which were settled farming sites (Hiebert, 2002). It is possible that like the people in the Kopet Dag 6 sphere, people at Parkhai II were settled farmers. However, there is no direct evidence to support farming. It is also associated with Late Bronze Age sites in the Sumbar Valley (southwestern Turkmenistan) due to burial characteristics and pottery.

Figure 1. Burial chamber construction (Khlopin, 1981).

The burial chambers were usually 0.9-2.0m below the contemporary surface and were reached by through a side entrance covered by a stone slab (Khlopin, 1981; Dani & Masson, 1999) (Figure 1). They were round, collective tombs with multiple burials (Petrie, 2013). Tombs were often collective burials (Khlopin, 1981) For example, Chamber 24 (Figure 2) had a woman (23-25 years old) buried with two pottery vessels and a bronze pin, a child (8-9 years old) buried with bronze earrings and a steppe tortoise shell, and two infants buried without grave goods (1981). Additionally, chambers were used for subsequent burials; bones of the first burial were pushed deeper into the chamber and the newer burial took their place (Khlopin, 1981). It is unclear how Khlopin came to this conclusion, but it may have been based on stratigraphy. The collective tombs with multiple burials are similar to those at Ilgynly-depe, uniting them under a similar cultural sphere in southern Turkmenistan during the Early Bronze Age (Petrie, 2013). Interestingly, the burials do not seem to emphasize wealth or status (Petrie, 2013). They are unique because they are completely separate from the residential part of the settlement (Petrie, 2013). This separation of burial and residential areas groups Parkhai II culturally with Late Bronze Age burials in the valley region of Southern Turkmenistan (Parkhai I, Sumbar I, Sumbar II, Yangi Q’ala) (Petrie, 2013).

Figure 2. Burial Chamber 24. Woman with child and two infants. (Khlopin, 1981)

Additionally, bronze six spiral double-headed pins were among some of the most striking finds at the burial (Khlopin, 1981, Dani & Masson, 1996). The pins (Figure 3) all had more than four loops (Khlopin, 1981). The Parkhai II pins are distributed all over the Sumbar Valley in Southwestern Turkmenistan, once again uniting this cultural area (Khlopin, 1981). According to Hiebert (2002), these bi-spiral pins help associate Parkhai II with Kopet Dag 6 cultural region. The Kopet Dag 6 cultural region, in the foothills of the Kopet Dag mountains, had farming settlements (Hiebert, 2002). These settlements used dams to irrigate the already fertile loess soil (Hiebert, 2002). Though the Parkhai settlement itself has yet to be excavated, the association with Kopet Dag 6 suggests that people at Parkhai II could have been settled farmers.

Figure 3. Bi-spiral pins at Parkhai II (Objects 1-8). ( Khlopin, 1981)

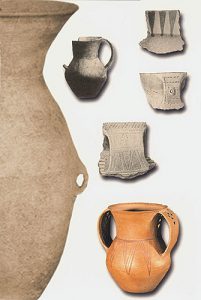

The pottery was a highlight of the site. Khlopin uncovered 300 ceramic vessels (Figure 4), which were made by hand without a potter’s wheel with a high level of perfection (1981). Ceramics were gray-black, engraved with designs and motifs (Salvatori et al., 2005). The earliest pottery had impressed or burnished engravings, but later pottery had no designs (Khlopin, 1981). Khlopin uses the pottery characteristics to link Parkhai II culturally with other sites in Southern Turkmenistan. It has a relationship to Late Bronze Age Sumbar cemetery sites due to similar ceramic traits of spouts, tube shaped feet, and button handles (Khlopin, 1981). This cultural association with Late Bronze Age sites based on pottery characteristics was discussed earlier in burial descriptions. According to Salvatori et al. (2005), Turkmenistan during the 3rd millennium B.C. (Early Bronze Age) has two distinct cultural regions based on pottery. One region is to the west with gray-black ceramics and one is to the east with polychrome ceramics. Parkhai II is grouped with sites west of Ashgabat, which are marked by gray-black ceramics with engraving and motifs (Salvatori et al., 2005).

Figure 4. Gray-black pottery at Parkhai II. (Khlopin, 1981).

Conclusion

The Parkhai II cemetery is an intriguing burial site in the Sumbar Valley Region of southwestern Turkmenistan. It seems to date to the Early Bronze Age, but information currently dates the site to a broad time range (3000-2250 B.C.). Direct dating techniques are needed to confirm that this was an Early Bronze Age site. It is culturally associated with other Early Bronze Age sedentary farming sites in the Kopet Dag foothills. These associations suggest that the Parkhai settlement was a sedentary farming group. The Parkhai II cemetery itself does not confirm the presence of farming in the area. The Parkhai settlement needs to be excavated to ascertain this information. The beautiful pottery at Parkhai II was a highlight of the finds and helps link Parkhai with the Sumbar cemetery from the Late Bronze Age and to Early Bronze Age sites west of Ashgabat. The cemetery site itself and the Parkhai II settlement would both benefit from further study and excavations.

Works Cited

Brummell, P. 2005. Turkmenistan. Globe Pequot Press Inc.

Dani, A., Masson, V. 1999. History of Civilizations of Central Asia- The Bronze Age in Khorasan and Transoxania. Motilal Banarsidass, 194-235.

Gubaev, A., Koshelenko, G., and Tosi, M. 1998. The Archaeological Map of the Murghab Delta Preliminary Reports 1990-95. IsIAO, Roma, 5-13.

Hiebert, F. 2002. The Kopet Dag Sequence of Early Villages in Central Asia. Paléorient, 28(2), 25-41.

Hiebert, F., Kurbansakhatov, K., and Schmidt, H. 2003. A Central Asian Village at the Dawn of Civilization: Excavations at Anau, Turkmenistan. UPenn Museum of Archaeology, Philadelphia, 21-162.

Khlopin, I.N. 1981. The Early Bronze Age Cemetery of Parkhai II: The First Two Seasons of Excavations: 1977-1978. Soviet Anthropology and Archaeology, 19(1-2), 3-34.

Petrie, C. 2013. Ancient Iran and its Neighbors: Local Developments and Interactions in the 4th Millennium BC. Oxbow Books, Oxford, U.K.

Salvatori, S., Masson, V., Muzio, C., Sarianidi, V., Vidale, M., Littvinskjj, B., Biscione, R., and Cattani, M. 2005. L’eta del Bronzo dell’Asia Centrale meridionale. Il Mondo dell’Archeologica. http://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/l-eta-del-bronzo-dell-asia-centrale-meridionale_%28Il-Mond o-dell%27Archeologia%29/. (translated with Google Translate from Italian).

Terekty-Aulie

December 7, 2017

Alternate Spellings:

Terekty-Auliye, Terekty-Aulie, Теректы-Аулие (Cyrillic)

Introduction and Geographic Location:

Coordinates: 48°12’44’’ N and 68°36’37’’ E

Elevation: 498 m

Terekty Aulie is an archaeological site in Central Kazakhstan featuring 3 granite hills with petroglyphs and multiple burial areas dating to the Bronze Age (2nd century BCE), the Early Iron Age and the 18th/19th centuries. The site is located in the district of Ulytau (Ulutau) in the Qaraghandy (Karaganda) region (Lymer 2015: 96). Terekty Aulie is ~90km northeast of the city Jezqazghan (Zhezkazgan) and ~20km north of Terekty Station (Lymer 2015:96, Rogozhinskiy 2011: 31). Using GoogleEarth, I measured the main area of the granite hills to be approximately 17,439 square meters. While the region is located in the heart of the desert steppe, this site is located in the mountainous area of the Terekty Hills, which are within the larger mountain Range known as the Ulytau (Ulutau) Mountains (Lymer 2015: 96). Jezqazghan (Zhezkazgan) is known for its abundance of oxidic copper, which was a prime resource for mining and creation of goods during the Bronze Age (Lymer 2015: 97).

Research on the site has mainly focused on the petroglyphs, which have been attributed to the pastoral nomads living in the area during the Bronze Age. Today, the site is an important religious location because of the petroglyphs and their connection to Islam (Lymer 2014).

Archaeology:

The site was first recorded in the 1940s by Kazakh archaeologist, A. Kh. Margulan (Samashev et al 2000: 4). Between the years of 1946 and 1950, Margulan led many field expeditions throughout the Ulytau area and which was when he first explored and noted Terekty Aulie (Tursinbaeva et al 2016: 172). Unfortunately, not much of this information was published and the original documents are difficult to find online.

In 1996, a program was started to continue research at the site by the A. Kh Margulan Institute of Archaeology led by Zainolla Samashev. (Samashev et al 2000: 4).

Findings and Interpretations:

As mentioned, Terekty Aulie encompasses 3 granite hills, which are engraved with mostly zoomorphic figures. The petroglyphs are mainly carved on the flatter surfaces of the hills, but also occasionally on the more vertical wall-like slopes (Samashev et al 2000:5). Typically rock art from this time period and region is found on sandstone because it is a much softer stone to carve into and makes it easier to create detailed images. Terekty Aulie is a unique example because it was created on granite using a technique of deep pecking and smoothing over, leaving us with the polished final product we see today (Lymer 2015: 96, Samashev et al 2000: 5). As with many petroglyph sites, it is difficult to determine exactly what the site represented or was used for. The site has more recently been adopted as an area for Islamic pilgrimage, which will be discussed below, but it is impossible to say what its exact purpose was at the time of its creation based on the information available.

Images of horses make up approximately 90% of the petroglyphs, but other images include lines, chariots, dots, bulls, Bactrian camels, goats, feline-like creatures, snakes and deer (Lymer 2015: 96-97, Rogozhinskiy 2011: 31). Horse imagery is common in Central Asia because of the important role these animals played in pastoral nomadism. Pastoral nomadism was a dominant lifestyle in Central Asia beginning around the Bronze Age that relied on mobility and herding of animals. Horses provided means of transportation as well as a resource for meat and secondary products (i.e. milk), which made them a prominent aspect of the nomadic lifestyle (Cunliffe 2015). It seems likely that the individuals who created the petroglyphs at Terekty Aulie lived a nomadic lifestyle because of the emphasis on horses in their art (Tursinbaeva et al 2016: 171).

The petroglyphs found at Terekty Aulie have been connected to the Seima Turbino phenomenon based on the similarities in horse image style to other zoomorphic designs in Central Asia. The “solid bodies, curved necks and prominent manes,” on the horses, which make up the majority of petroglyphs at Terekty Aulie, are comparable to images of horses found on daggers from Seima Turbino sites (Samashev et al 2000:5). This phenomenon is attributed to the rise of pastoral nomadism, which influenced the flow of ideas, materials and people on the Central Asian landscape.

Figure 1: Horse petroglyphs at Terekty Aulie

Lymer 2015

Non-horse images, specifically the deer and feline animals, are more similar in style to petroglyphs found in the Altai Mountains, which are considered to be from an early Scythian culture (Samashev et al 2000: 5). Images of humans are uncommon at Terekty Aulie, but the few instances of anthropomorphic figures have generated many varying interpretations. For example, the image below, known as “the antenna”, has a circular design with animals drawn inside the circle and a human with a twisted leg standing beneath it. Some believe that this image is of the sun or another astrological figure, which could be related to a type of “solar symbolism” while others imagine that it represents a human on a shamanistic journey (Samashev et al 2000: 6, Lymer 2015: 99, Tursinbaeva et al 2016: 171). Personally, the shape of the petroglyph reminds me of the desert kites found in Eastern Central Asia and the Middle East which were are dated to the Iron Age. These kites are hypothesized to be hunting traps used to efficiently herd ungulates to a pit humans could easily kill them (Zeder et al 2013: 110, 114). Below is the petroglyph at Terekty Aulie in comparison with petroglyphs of desert kites in Syria (Figure 2, Figure 3).

Figure 2: Image of “the antenna” at Terekty Aulie, possibly depicting a desert kite

Samashev et al 2000

Figure 3: Image of petroglyphs in Syria possibly depicting desert kites

Zeder et al 2013

To the southeast of Terekty Aulie, there is a small cemetery that has been dated to the Bronze Age. The cemetery includes 20 burials that have been attributed to the Alakul culture or the Begazy-Dandybai culture, which are both regional variations within the larger Andronovo culture describing pastoral nomads living in Kazakhstan and Southern Siberia (Lymer 2015: 97, Lymer 2010, Frachetti 2008). The site also includes scattered Neolithic tools, Early Iron Age burials in the style of kurgans and a more recent, 18th/19th century mausoleums (Samashev et al 2000: 4).

In the present day, Terekty Aulie serves as a sacred Islamic shrine because some of the images have been interpreted as being Islamic figures. Currently, a wooden post sits at the top of one of the engrave granite hills, which replaced a stone shrine shown in Figure 4 that had been there until 2001 (Lymer 2014: 3).

Figure 4: Shrine at Terekty Aulie (before 2001), replaced by wood post in 2001

Lymer 2014

Terekty Aulie is a place of pilgrimage because it is believed to hold healing properties that can help situations of sickness or infertility (Lymer 2010). This belief comes from the story of Khazrat ‘Ali, the son-in-law of the prophet Muhammad, visiting Terekty Aulie with his horse, Dudul. Khazrat ‘Ali was wounded when he arrived to the site and fell asleep on the rocky hills expecting to die. Instead, when he awoke he found that at all his wounds had been healed (Tursinbaeva et al 2016: 171). In the rock art are images of human footprints and horse hoof prints, which are thought to belong to Khazrat ‘Ali and his horse (Figure 5, Figure 6) (Lymer 2014: 4).

Figure 6: Image of human foot print petrogylphs at Terekty Aulie

Lymer 2004

Figure 7: Image of horse hoof print petroglyph at Terekty Aulie

Lymer 2004

At the base of one of the hills are 18th/19th century mausoleums, which have more recently been fenced in and expanded with the addition of modern mausoleums. Individuals make the pilgrimage to Terekty Aulie, not only for its healing properties and connection to Islam, but also to pay homage to the people buried in the mausoleums. Individuals often hold ritual meals near the base of the hill, which are rooted in prayer, specific meal preparation and memorial offerings (Lymer 2010, Lymer 2014: 4).

Dating:

The site has been dated to the Bronze Age (approximately during the 2nd century BCE) using contextual clues. Since the petroglyphs are carved into rocks, they are impossible to date using typical scientific measures such as carbon dating or electron spin resonance dating. The archaeologists researching this site instead used methods of comparison and inference to come up with an approximate date but these are not scientifically proven dates.

The cemetery southeast of Terekty Aulie was dated to the Bronze Age based on its materials. However, there is no conclusive link between the cemetery and the petroglyphs to prove that these two sites were created at the same time or by the same group of people (Lymer 2015: 97). Unfortunately, there is little information published about this cemetery and the materials recovered from it. The knowledge that Jezqazghan was a city known for copper resources during the Bronze Age makes it more likely that Terekty Aulie was used during the same period, but again it is impossible to make definite conclusions about when the petroglyphs were created (Lymer 2015: 97).

A secondary method of dating used at the site was a comparison technique to examine the similarities and differences between this site and other sites in the area with more certain dates. As mentioned previously, the style of the horse petroglyphs are similar to designs from Seima Turbino sites, which are dated between 2200–1700 BCE (Lymer 2015: 97).

Conclusion:

While the petroglyphs at Terekty Aulie produce archaeological difficulties with regards to dating and deciphering the original purpose of the site, the site also provides an amazing opportunity to understand how the area has changed over time. The remains from multiple time periods, the unique material of rock and the connection to Islam continues to attract a variety of people. From tourists to researchers to individuals on religious journeys, Terekty Aulie is an important site to many.

To check out a 3D interactive model of the site created by Kenneth Lymer, please see the link below!

https://sketchfab.com/models/7e0ca19553d1402e8420c640dabe4ca0

Works Cited

Cunliffe, Barry. “Horses and Copper.” Steppe, Desert and Ocean. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015. 71-109.

Frachetti, Michael D. “An archaeology of Bronze Age Eurasia.” Pastoralist Landscapes and Social Interaction in Bronze Age Eurasia. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2008. 31-71.

Lymer, Kenneth. “Rock Art and Folk Islamic Practices in Central Asia.” Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer Science & Business Media, 2014.

Lymer, Kenneth. “Rock Art and Religion: The Percolation of Landscapes and Permeability of Boundaries at Petroglyph Sites in Kazahkstan.” DISKUS. 11 (2010).

Lymer, Kenneth. “The Petroglyphs of Terekty Aulie in Central Kazakhstan.” Expression. 8 (2015).

Rogozhinskiy, Alexey E. “Rock Art Sites in Kazakhstan.” Rock Art in Central Asia. Ed. Jean Clottes. Paris: International Council on Monuments and Sites, 2011. 9-43.

Samashev, Zainolla, et al. “The Petroglyphs of Terekty Aulie, Central Kazahkstan.” International Newsletter on Rock Art. 5 (2000).

Tursinbaeva, K. S., et al. “Petroglyphs Terekty-Aulie in Central Kazahkstan.” Eurasian Journal of Ecology. 38.2 (2016).

Zeder, Melinda A., et al. “New perspectives on the use of kites in mass-kills of Levantine gazelle: A view from northeastern Syria.” Quarternary Internation. 297 (2013).

Kulbulak

December 7, 2017

By Jack Leddy

Alternative Spelling: Kul’Bulak

Coordinates: 41°00′31′′N, 70°00′22′′E (Flas, 2010)

Elevation: 1044m asl

Geography: Kulbulak is an open-air Paleolithic site in the Tashkent region of Uzbekistan, lying at the base of the Chatkal range of the Tian Shan mountains. The Tashkent region is in the northeast of Uzbekistan and contains its capital, also named Tashkent. Kulbulak is not particularly remote, as it is only a few kilometers from the town of Angren (Flas, 2010). Kulbulak was also a prime location for prehistoric inhabitation, having all the resources necessary for their way of life, including a nearby source of flint at Kyzyl-Alma, evidently used to make much of the tool assemblage at Kulbulak. Additionally, Kulbulak is close to the Dzhar-sai and the Kyzylalma rivers (Vandenberghe, 2014), along with several smaller brooks and streams which would have provided a source of drinkable water to Paleolithic peoples.

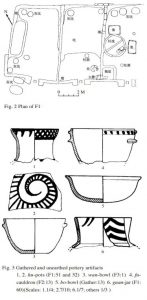

Excavation and Dating: Kulbulak was first discovered in 1962 by M.R. Kasymov, and has been excavated several times since. To date, the total area that has been excavated is about 600 square meters (Flas, 2010). In this area, close to 70,000 artifacts have been recovered (Vandenberghe, 2014). Much like many other open-air Central Asian sites, the dating at Kulbulak is quite complicated, especially due to the remarkably complex stratigraphy. The excavated artifacts were initially relatively dated, as the bladelets found are quite similar to those at another Uzbek site, Dodekatym 2, which has been dated to about 23ka (Flas, 2010). More recent attempts, however, employed luminescence dating, a method which examines when sediments were exposed to light, revealing when they were deposited. The dating resulted in a range of about 39ka to about 82ka. This suggests an Upper Paleolithic origin of more recent layers, and a Middle Paleolithic origin of the deeper ones.

Lithic Analysis: As indicated by the luminescence dating, the tool assemblage of the site has been separated into two main categories loosely based on their stratigraphic layers, representing the technology of either the Middle or Upper Paleolithic. Kasymov originally thought there was a third layer, consisting of Lower Paleolithic Acheulian tools, but there is no evidence to support his hypothesis (Dani, 1999). The entire tool assemblage at Kulbulak is overwhelmingly flint-based, with a few instances of limestone, diorite, and quartzite (Vishnyatsky, 1999). The Upper Paleolithic tool-kit consists of cores, bladelets, and debitage, as is to be expected of an Upper Paleolithic assemblage in this region, but the stratigraphic layers also contain several tools indicative of a Middle Paleolithic core and flake industry.

A sample of the tool assemblage at Kulbulak, image from (Flas, 2010)

Another interesting anomaly of the Kulbulak artifacts is the presence of several “Pseudo-tools” (Vandenberghe, 2014). These pseudo-tools take the shape of denticulate blades, but they have been discounted by some as having been made naturally by alluvial processes rather than deliberately by humans. This is supported by the fact that much of the sediment where the tools were excavated is attributed to flood deposits from the nearby rivers (Vandenberghe, 2014). Kulbulak is also made distinct by the presence of bifacial Middle Paleolithic hand-axes. These bifaces, shaped into leaf-shaped points, differentiate Kulbulak from nearby sites, as it is the only site at which such tools are found. In fact, there are no other bifaces at all in the general area. Most of the other sites were limited to core and flake industries in the Middle Paleolithic.

Anthropological Analysis: Unfortunately, due to a lack of organic material found at Kulbulak (with the exception of a single human molar and a few assorted animal bones), any understanding of human activity must rely on mostly conjecture. Furthermore, the complex stratigraphy makes it difficult to make assumptions about the technological progression of Kulbulak’s inhabitants, but it lends credence to another theory regarding the cultures of the area. Analysis of multiple nearby sites has resulted in the idea of a ‘Kulbulakian’ culture existing throughout the region (Kolobova, 2014). The Middle to Upper Paleolithic tool assemblage indicates that this culture was present for a long period of time, as was the site itself, though perhaps intermittently. Despite the nomadic tendencies of Upper Paleolithic Central Asian people, the allure of a source of abundant flint could have convinced the Kulbulakians to maintain a more sedentary community than most of their contemporaries.

Single human molar found at Kulbulak, image from (Flas, 2010)

The site’s proximity to water also makes Kulbulak a prime location for a settlement, but despite these facts, there have been no hearths or fire pits discovered (Vishnyatsky, 1999). This of course does not mean that hearths and fire pits did not ever exist there, but it contributes to the enigmatic nature of the site. Another discovery pertinent to anthropological analysis of Kulbulak is the Kyzyl-Alma site. Kyzyl-Alma is only about one kilometer away from Kulbulak, and the two sites seem to have been home to one group of people (Kolobova, 2014). The first piece of evidence for this hypothesis is that the tool assemblages of the two sites are remarkably similar. The second, and more compelling, piece of evidence is the proximity of Kyzyl-Alma to flint outcroppings (Kolobova, 2014). This is relevant because of the overwhelming number of flint tools unearthed at Kulbulak. It is likely that Kyzyl-Alma served as an excavating point for the raw material. Due to the fully formed tools found there (Kolobova, 2014), it can be inferred that the crafting of the tools took place at this site as well. The completed tools would then have been transported to Kulbulak. This hypothesis can be corroborated by the lack of cores in recent stratigraphic layers at Kulbulak, meaning they probably were not making new tools there (Kolobova, 2014).

As is the case with many Central Asian sites, the anthropological implications of Kulbulak remain clouded by uncooperative stratigraphy and lack of reliably datable artifacts, but through inference and examination of available data it is possible to form a vague picture of the lives of the Kulbulakians.

Sources

Dani, Ahmad Hasan., Masson, V.M., Harmatta, J., Litvinovski, B.A., Bosworth, C.E. History of

Civilizations of Central Asia. Vol. 1, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, 1999.

Flas, D., Kolobova, K., Pavlenok, K., Vandenberghe, D., De Dapper, M., Leschinsky, S., Bence,

V., Islamov, U., Derevianko, A., Cauwe, N., 2010. Preliminary results of new excavations at the Palaeolithic site of Kulbulak (Uzbekistan). Antiquity. 325.

Kolobova, K.A., Krivoshapin, A.I., 2014. Кульбалбекская культура в контексте

ауриньякского языка в Азии. Publishing Department of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnography.

Vandenberghe, D.A.G., Flas, D., De Dapper, M., Van Nieuland, J., Kolobova, K., Pavlenok, K.,

Islamov, U., De Pelsmaeker, E., Debeer, A.E., Buylaert, J.P., 2014. Revisiting the Palaeolithic site of Kulbulak (Uzbekistan): First results from luminescence dating. Quaternary International. 324, 180-189.

Vishnyatsky, Leonid, 1999. The Paleolithic of Central Asia. Journal of World Prehistory. 13, 28-

42.

Qiemo

May 21, 2017

(Written by Jonathan Rodriguez)

Alternative Spelling: Cherchen, Chärchän, Charchan, Qarqan, Shanshan // Chinese: 且末 (Qiĕmò)

Coordinates: 38°08′N 85°31′E

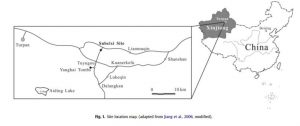

Geography + Borders

Qiemo exists as a region, considered as both a city and a county. Qiemo is located within the contemporary borders of the Xinjiang region of Northwestern China, landlocked and sharing borders with many Central Asian countries (Mongolia, Russia, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, India, etc.) and sits at a diverse crossroads of a geographic distinctiveness. Facing the south, the county lies on the northern foothills of the Kunlun Mountains and eastern foothills of the Altun Mountain range, scattered across the southeast end of the Taklimakan Desert perpendicular to the Altun and Tian Shan Mountain range. Qiemo town is found on the bountiful oasis within the desert, along the riversides of the Qarqan River that drains from the Tian Shan glacier banks across the Tarim Basin (Google Earth) (Stein 1995: 380).

Qiemo town claims ownership to many important excavated sites that lie in proximity to the town’s center, and due to its historic abundance in resources within the desert, consequently holds a rich historical importance as a geographic hub over trade and power.

Archaeology

Qiemo, the Tarim Basin, and the Taklimakan Desert are known for claiming origin to many incredible archeological finds that are established as well known artifacts of the region, and as milestone excavations celebrity to Central Asian archeological evidence in the formation of its prehistoric regional identity.

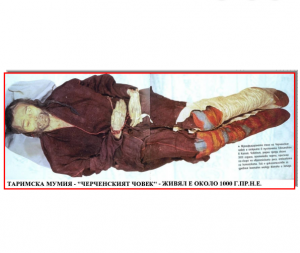

The most striking and important excavation is that of the famous Chärchän Man (Qarqan Man). In archeological debates on the “Indo-European problem” and the ethnographic information on the racial genetic identity of this early modern human, this particular Tarim mummy proves the most in tact – a spectacle questioning the construction of prehistoric migration direction and biological diversity in the region.

The excavation of the site, led by Victor H. Mair and J. P. Mallory in 1971, was carried out around 6 kilometers from Qiemo town in Zaghunluq village in the county (named after tuzluqqash, the rich salt mined from the very deposits that conduces the coincidental mummification process), uncovering a multitude of tombs, some untouched and some already discovered/looted. A number of things were found in the tombs, including drinking vessels, sheep’s heads, horse remains, animal skins (one of a horse and two od wild buffalo), organized tree limbs, tomb carving art, pottery, textiles, reeds, bone utensils (such as spoons, hair combs, cups), ritual yarn and wood (Anthony 2001: 77).

Figure 2: A preserved female corpse found in Tomb 85QZM 2 (Photo courtesy of excavation study by Dolkun Kamabri)

Focusing on the mummified corpses, Tarim tombs at large have held a number of mummies, buried meticulously amongst the several tombs and the organized objects within them. Of the corpses, the bodies of men, women, and even toddlers were found, mummified with intricate dress and objects. One corpse (one male found in Tomb 85QZM 2) was found traces of makeup on his face, braided hair, and colorful clothing. A female corpse was also found, with similar makeup (made of ochre in sun symbolism patterns) with artificial braided hair. These corpses were found in a tomb amongst 2 other decaying ones, with crossed arms and legs, buried amongst wall art (with animal and hand symbology) and items that may have been used as fire symbols (wooden objects, yarn0, on an enclosed tomb covered with layers of material (tree limbs, willow and reed mats, animal hide), found in proximity to horse skull and legs (Kamabri 1994: 5-6). Amongst these corpses, a small oval tomb was also found, holding the corpse of an infant (~ < 3 months old) wrapped in purple wool on its body and blue wool on its head, and buried with other fabrics, a leather “baby bottle” in proximity to a sheep’s head buried nearby (Kamabri 1994: 5).

Figure 3: The Charchan Man. (Photo courtesy of excavation study by Dolkun Kamabri)

Anthropology + History

Using radiocarbon dating, the Bureau of Cultural Relics of Beijing tested 5 samples within the tomb, all indicating dates around 1000 BCE. The clothing and art style and food items emulating Bronze Age cultures in the tombs also relegate connection to modern Uyghur people, indicating possibility of being related to the Saka people of the area 3,000 years age (Kamabri 1994: 5-6).

Looking closer at the site details and context, considering Qiemo as an oasis site in the Taklimakan desert, is found to be an important site on the Silk Road, both historically and contemporarily in Northwestern China, which contributes to the high concentration of rich archaeological material found on the Basin.

The contemporary geopolitical context of these findings are important, as they debate the historical legitimacy of the ancestral lineage and agency of the Uyghur people currently in the area (amongst a diversity of indigenous lineages within the area). Previous studies based on linguistic analysis of ancient texts from the site come to the conclude that this Tocharian ancient language belonged to the Indo-European language family (Pringle 2010: 32-35) More recent studies of mitochondrial DNA of the several mummies on the basin provide to challenge Mair’s previous assertion about Caucasoid/Europoid DNA constituting the oldest dated mummies in the Tarim Basin, including research on the nearby Loulan Beauty and revisiting Charchan DNA sources. Archeologist Zhou Hui, amongst other academics, excavated nearby ancient cemeteries are currently conducting research to find DNA data connesting to lineages in Siberia and East and South Asia (Xiequan, M. 2010). Disparages between ancient Uyghur inscriptions, DNA data, and constant new archeological finds keep this debate of the Indo-Europian vs Asian ancestry debate rolling, sensitive to contemporary Uyghur identity and historical pride.

Qiemo is clearly visible on the map, populated in the oasis strip laying on the the Qarqan River, with its respective surrounding geography.

Bibliography

Anthony, D. (2001). Tracking the Tarim Mummies. Archaeology, 54(2), 76-84.

Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41779400

Bovington, C. H., Jr., R. H., Mahdavi, A., et al. (1974). The Radiocarbon Evidence for the Terminal Date of the

Hissar IIIC Culture. Iran, 12, 195. doi:10.2307/4300513

Kamberi, D. (1994). The Three Thousand Year Old Charchan Man Preserved at Zaghunluq : Abstract

Account of a Tomb Excavation in Charchan County of Uyghuristan

http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp044_charchan_man.pdf

Kamberi, D. (1986). Tarim Arkheologjyasidiki Bir Qetimliq Zor Tepilish, Xinjiang Miidiiniy Yadikarliqliri, 1-11.

Pringle, H. (2010). Battle for the Xinjiang Mummies. Archaeology, 63(4), 30-35. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41780584

Stein, A. (1925). Innermost Asia: Its Geography as a Factor in History. The Geographical Journal, 65(5), 377-403.

doi:10.2307/1782547

Xiequan, M. (2010, April 29). Xinjiang discovery provides intriguing DNA link. Retrieved May 9, 2017, from

http://news.xinhuanet.com/english2010/china/2010-04/29/c_13272928.htm

Qijiaping

May 10, 2017

Alternate Spellings: Qi Jiaping, Ch’i-Chia

Chinese: 齊家坪

Location:

35º29’48.40” N 103º49’58.44” E (Google Earth)

Elevation:

6363 ft

Qijiaping is a Late Neolithic site located just outside of Qijiaping Village in Guanghe, Gansu, China, about 35 miles east of the Linxia Hui Autonomous District. At an elevation of around 6,000 ft, Qijiaping is nestled between the Tibetan and Loess plateaus on a terrace above the Taohe River, as well as roughly 300 miles east of the Yellow River (Zhimin, 1992). Qijiaping site covers an area of 1.5km² and neighbors a number of surrounding cities and villages such as Paizipingcun, Shijiatan and Dongping.

The Qijiaping site was first discovered and excavated by Swedish geologist and archaeologist Johan Gunnar Andersson in 1924. Andersson’s initial excavation not only revealed numerous graves and preserved artifacts, but was simultaneously the discovery of an entire culture. Qijia Culture, named after it’s respective locale, is the only known Neolithic culture in China that shows northern Eurasian influence (Xia, 2008). Qijia culture is centered by the archaeological site at Qijiaping, but spans further, reaching as close as the upper Taohe, Daxia and Weihe rivers in the Gansu Province and as far as the Huangshi Basin in the upper reaches of the Yellow River in Qinghai (Zhimin, 1992). Additional site discoveries and excavations, like those of Chinese archaeologists Pei Wenzhong and Xia Nai in the neighboring villages of Yangwawan and Cuijiazhuang in the 1940s and 50s, spearheaded the conceptualization of Qijia culture. Their discoveries, among others, concluded that Qijiaping was not unique, but rather the piece of a larger puzzle.

(Map of Qijiaping (4) and other Qijia culture sites like Dadiwan (1), Zongri (2), Lajia (3), Shangsunajia (5)) (Ma, Dong et al. 2013)

Qijiaping and Qijia culture have been dated back to c. 2200 – 1900 BCE via radiocarbon analysis and subsequently discerned to be a transitional period between the end of the Neolithic Age and the beginning of the Bronze Age (de Laet, Dani 1994). This transcendence of era is directly manifested in retrieved artifacts from the site(s). In a 1975 excavation of Qijiaping, dozens of artifacts were unearthed, ranging from stone tools and clay pottery to bronze mirrors.

Qijia pottery however is nothing ordinary. In fact, it is some of the best evidence of transcultural influence and trans-Eurasian contact to date. Qijia pottery was crafted by hand with fine red ware and a coarse reddish-brown ware, a commonplace resource of China. What is markedly different about Qijia pottery however is its design. While it has its own stylistic characteristics, Qijia pottery is often found with comblike designs and amphora-like vases, both of which were presumably alien to China. Anthropologists suggest this to be evidence of cultural contact and trade across Eurasia.

(Potter urn: container (left-up, height 11.8 cm); Painted pottery fragment with triangle design: (right-up, height 4.7 cm); Pottery fragment from the ear of vessel: (up of the right-mid, height 4 cm); Pottery fragment from the ear of vessel: (bottom of the right-mid, height 4.8 cm); Painted pottery amphora with the pattern of triangle: food container (height 10.2 cm)) (Chen 2013)

The bronze mirror found in the 1975 excavation of Qijiaping serves a similar purpose. The discovery of the mirror dismantles all presumptions of cultural development in the Gansu Province – it suggests that early Chinese bronze casting may have originated in Western China, and may even have lineage to bronze casting in Central Asia and the Iranian area, suggesting, like the pottery, the existence of trans-Eurasian exchange (Chen, Mao, et al. 2012).

(Bronze mirror, Gansu. Qijia culture (2400 – 1900) National Museum of China)

Stone and bone tools were also found at the site, keeping the conception of Qijia culture in the Neolithic Age.

In addition to tools, pottery and bronze mirrors, the 1975 excavation of Qijiaping yielded hundreds of animal and human bone remains, shedding light on lifestyle, tradition and even diet. The discoveries reveal a sedentary lifestyle based on agriculture. Pig, sheep, goat and cow remains suggest domestication. Furthermore, large quantities of millet have also been found and is surprisingly the impetus behind the search for evidence of trans-Eurasian trade. Human bones from Qijiaping were isotopically analyzed to study the diet patterns of the Qijia people and unexpectedly revealed the existence of not only millet in the diet, but wheat and barley as well. The presence of wheat and barley in Qijia diet is crucial because at the time, wheat and barley only really existed in the west. Therefore to be included in their diet, the Qijia people must have had contact and trade with western civilizations (Ma, Dong, et al. 2013).

Qijiaping and its neighboring Qijia sites have also produced over 800 burial sites since discovery in 1924. These burial sites, organized in cemeteries of various size, express social sophistication and potential hierarchical tradition in Qijia culture. For example, while many burials are singular, it is not uncommon to find a man and woman buried together. Moreover, there are even cases in which two flexed women are buried on either side of a deceased man, indicating the inferiority of women and their subjugation to men in Qijia culture. Furthermore, grave goods vary greatly across Qijia sites, suggesting some form of social hierarchy. For example, at the Huangniangniangtai cemetery in Wuwei County, Gansu Province, men are buried with up to 37 pieces of pottery. At the Qinweijia cemetery in Yongjing County, Gansu Province, men are buried with up to 68 pieces of pigs’ mandibles. Anthropologists believe this to be evidence of social hierarchy in Qijia culture (de Laet, Dani 1994).

Qijiaping is one of the most imperative archaeological sites in ancient western China. The discovery of Qijiaping in 1924 not only unearthed artifacts but an entire lost culture. Qijiaping has drawn attention to a seemingly stagnant area. It has become one of the most pertinent archaeological sites in China today and has shaped the ways in which anthropologists understand prehistory in Eurasia. Qijiaping has enlightened the anthropological community to trans-Eurasian trade and has opened new doors to understanding how the west and the east are more connected than previously presumed.

Works Cited

Chen, Honghai. “The Qijia culture in the upper Yellow River valley.” A Companion to Chinese Archaeology. Blackwell. pp 105-124. 2013.

Chen, Jianli, Mao, Ruilin, Wang, Hui, Chen, Honghai, Xie, Yan, Qian, Yaopeng. The iron objects unearthed from tombs of the Siwa culture in Mogou, Gansu, and the origin of iron-making technology in China. Wenwu (Cult. Relics) 8,45-53. 2012. (in Chinese)

de Laet, Sigfried J., Dani, Ahmad Hasan. History of Humanity: From the third millennium to the seventh century B.C. UNESCO, 1994.

Ma, M., Dong, G., Liu, X., Lightfoot, E., Chen, F., Wang, H., Li, H., Jones, M. K. Stable Isotope Analysis of Human and Animal Remains at the Qijiaping Site in Middle Gansu, China. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 13 Dec, 2013.

Xia, Zhihou. Chinese History: Qijia Culture. Encyclopedia Britannica. 5 Sep, 2008.

Zhimin, An. “The Bronze Age in eastern parts of Central Asia.” History of Civilizations of Central Asia, volume 1: The Dawn of Civilization: Earliest Times to 700 B.C. UNESCO. pp. 308 – 325. 1992.

Dashly

May 10, 2017

NB: Not all of the sites’ coordinates are published, and those that are are somewhat inaccurate, requiring the author to survey the landscape on Google Maps to find the sites. Dashly 3 is not visible on Google Maps.

Dashly 1 : 37°05’15.75″ N, 66°24’02.98″ E. Elevation: 286 meters.

Map Data: Google, US Dept of State Geographer, Image Landsat, Copernicus 2017

Dashly 1 from elevation of 2.47 kilometers. Map Data: Google 2016, Image 2017, copyright CNES/Airbus

Introduction

Dashly (Dashlyji, Dashli, Dašlī, Dashlydzhi, Dashlin Oasis, Russian: дашлы, Dari (Afghan Persian): داشلى , داشلي) is a collection of 41 archaeological sites comprising an ancient urban set of settlements located in Jowzjan and Balkh Provinces, Northern Afghanistan (Amiet 1994). These are not to be confused with the sites called ‘Dashlyji-depe’ in Turkmenistan. The data on other Dashly sites is often difficult to find, even online. Thus, only Dashly-1 and Dashly-3 will be discussed in detail. There were no images of the grave goods or other findings online or in books, so images of the sites will be shown.

The Dashlyji sites date from the Eneolithic Age, also known as the Chalcolithic or the Copper Age. The nearest town is Faruk Qala, approximately 8 kilometers south-southwest of Dashly-1. The coordinates for Faruk Qala are 37°01’30.49″ N, 66°21’24.51″ E and at an elevation of 287 meters. The nearest large city, Aqcha, is 27.3 kilometers southwest of Dashly-1, and its coordinates are 36°54’47.20″ N, 66° 11’12.94″ E and at an elevation of 293 meters. The area is located in an arid area characterized by vast deserts, the Amu Darya River, formerly known as the Oxus River, towns and villages, and sand dunes. Roads, paths, and game trails course through this landscape. Sand dunes and other geological formations obscure the ruins on mapping technologies. The Dashly sites contain architectural ruins, human and animal burials, and artifacts such as ceramics, metal objects. The Amu Darya river is 30 kilometers to the north. 75 kilometers to the south is the city of Sheberghan, which is the site of a potential natural gas development project (See Ministry of Mines, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan for the Asian Development Bank 2009). While natural gas was presumably not used during the Dashly sites’ occupation, the natural gas project could introduce an economic stimulus that would provide impetus for further investigation.

Site Summaries and Finds

The settlements also include burials of both people (Livinsky and P’yankova, 1993:380) and sheep sacrifices (Masson and Sarianidi, 1969; Joglekar 2006:234). Some of the other findings include jewelry and ceramics similar to those of the Andronovo assemblages (Kuz’mina, 1996: 286; Sarianidi, 1977, fig.6). The presence of fortifications and sheep indicates that settlement was intentional and extensive. The ceramics found were dated to multiple stages: around 1400-1200 BCE, and the Namazga, V and VI periods, around 2100-c.1800 BCE (Kuz’mina 2007:286 ;Shaw and Jameson 2008:416). Kuzmina posits that Dashly was occupied on-and-off for a long time. The ruined buildings were re-used as burial grounds at a later date (Litvinsky and P’yankova, n.d.:371), possibly indicating this intermittent use.

Sarianidi argued that the people who who inhabited the Dashly sites were Indo-Iranians (Sarianidi, 1976; Lamberg-Karlovsky 2002:70). There were 87 graves discovered, and excavations revealed that Sarianidi specifically compared Dashly-3 to temples from Mesopotamia (Lamberg-Karlovsky 2002:70). He did this to present the possibility of influence from Mesopotamian cultures on Dashly’s inhabitants, indicating contact with multifarious peoples.

Dashly 3 Temple, (Kohl 1983:21, fig. 2.3)

An image of the Dashly-3 ‘palace’ (Kohl 1983:22, fig.2.4).

An image of the Dashly-3 ‘palace’ (Kohl 1983:22, fig.2.4).

According to radiocarbon dating, these sites have been dated as follows: Dashly-1 has been dated to 1250 BCE and 1570 BCE, while Dashly-3 has been dated to 1490 BCE (Dulukhanov et al. 1976). Dashly-1 is the remains of a fortified building and associated burials. Dashly-1 and Dashly-3 both have buildings often termed ‘palaces’ (see Salvatori, 2000:98). The buildings’ constructions typically involve the use of square or rectilinear forms, multiple small rooms, and walls. Dashly-3, however, has a circular building as part of the temple. The buildings’ actual uses and the cultural attributes of their occupants and/or users, however, is still a matter of conjecture. However, Dashly-3 is the only site with a supposed ‘temple’ complex. Sarianidi’s assertion that the ruins at Dashly-3 were once those of a temple, particularly a proto-Zoroastrian temple, is contested (Amiet 1994). Sarianidi argues that the rituals involving fire, which are rituals associated with Zoroastrianism, happened at temples throughout the BMAC (Sarianidi and Puschnigg 2002; Sarianidi 1994). According to Pilipko, the Dashly sites’ location along the river and away from the mountains was ideal for defense (Pilipko 2015:82). The ruins and burials have been subject to unauthorized excavations, further obfuscating the sites’ histories (Amiet 1994).

Dashly in Historical Context

Central Asia has been peopled since the paleolithic, its people migrating to find resources and avoid the harsh weather. The complex is located in the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC), which spans parts of Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The BMAC consists of the remains of the Oxus civilization, which is dated from approximately 2200-1700 BCE (Lamberg-Karlovsky 2013:1). Sarianidi argues that Indo-Iranians peopled the BMAC, linking the ancient Persian civilizations with those of the Indus Valley. Bactria was at one point part of the Persian and Greek empires. This area’s centralized location means that a multitude of people could of passed through or traded goods amongst the locals.

(Kaniuth, 2007:27)

The Dashly sites are as much a part of Afghanistan’s contemporary and future cultural heritage landscape as they are an anchor to Afghanistan’s past. The Dashly sites’ current situation is typical of many cultural heritage sites around the world in that they are situated in the midst of a protracted and destructive conflict. Tragically, many artifacts taken from Dashly and housed in the National Museum of Afghanistan have been destroyed during the wars. Currently, the United States is engaged in a war with the Taliban, an insurgent group in Afghanistan. this war threatens multiple archaeological sites, including the Dashly sites. The United States Central Command (USCENTCOM) requires military personnel and contractors to abide by Afghan cultural property law and to help protect these sites from harm United States Department of Defense – United States Central Command, 2004).

Important Investigators

Viktor Sarianidi (1929-2013), a Russian archaeologist born in the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic, discovered the sites. His works are famous, but somewhat difficult to find in English. He, along with his collaborators from the Soviet Academy of Sciences in Moscow, excavated the sites from 1969-1979, halting work when Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan (Salvatori, 2000:97). He also discovered a large amount of golden objects in Tillya Tepe, which drew much attention to the region.

Bactrian treasure – ram figurine. Not from Dashly, but a cool thing from the BMAC! (Kjullver, 2007)

Until his death, he was the foremost expert on the Dashlyji sites and is lauded for his discoveries, which elucidated Bactria’s and Margiana’s history and cultural connections between this region and its neighbors. Other investigators included V.M. Masson (1929-1910), who taught Sarianidi at the Central Asian State University.

Challenges and Lessons

Because of these sites’ location within a conflict zone, studying them and learning from their artifacts is jeopardized. The human and animal burials, ceramics, and metal artifacts gesture towards a long history of occupation and development of this currently arid location. Preserving the ruins and artifacts can provide Afghanistan with a wealth of knowledge that will empower future generations for years to come.

Bibliography

Further Reading

Gonur Depe

May 10, 2017

Also: Gonur Tepe / гонур депе (Russian)

Location: 38° 12′50′′N 62°02′15′′E (Vladimir Kufterin)

Elevation: 635 feet

Gonur-depe is a Bronze Age archeological site in Southeastern Turkmenistan, specifically located north of the city of Bayramaly (Kufterin). Researchers now know that this site, which has been translated from Turkmen and means “the gray hill”, is not a stand alone prehistoric site; it is one of and the largest of about 500 sites all located in the Murghab River delta (Molodin). Though the site seems barren now, situated in the Kara-Kum deserts of Turkmenistan, the roughly 4000-year-old site is believed to have thrived for a few centuries as ancient civilization and to have been dependent on the Murghab River, the sole stable water source with the Kara-Kum (Lawler).

Gonur’s initial discovery and preliminary archeological finds are interwoven into the past political and historical circumstances of the region. Even though Gonur’s civilization was initially studied in the early 1970’s, investigations came to a halt in 1979 due to Iran’s revolution and a war in Afghanistan, which blocked any archeologists from accessing the site (Lawler). Furthermore, Russian archeologists avoided investigating the area after the Soviet Union fell in 1990. These conditions stalled a thorough archeological study of Gonur until 35 years ago, when V.I Sarianidi was finally able to lead a thorough excavation (Molodin). The historical and political factors affecting Gonur’s discovery are interesting to consider when thinking to larger questions considering the relationship between science and politics.

Sarianidi’s excavation of Gonur proved to be fruitful, as this settlement is one of the largest Bactria-Margiana archeological complex (BMAC) sites, which was inhabited between 2300 – 1500 BC (Kufterin). For context, the term BMAC arises due to “Bactria” being the Greek term for modern day northern Afghanistan and “Margiana” being the Greek term for a town in modern day Turkmenistan (Molodin). Gonur’s discovery was significant not only because of the structures and artifacts found, but also because of the way it pushed scholars to acknowledge the region’s participation in and major contributions to an overall global trade amongst goods, ideas, and technologies (Lawler).

Archeologist Frederik Heibert observed Sarianidi’s initial observations, conducted field research under Sarianidi, and built upon the foundational knowledge known about Gonur-Depe. This site is one of many that he discusses in his text, Origins of the Bronze Age Oasis Civilization in Central Asia. Heibert’s text allows us to learn about specifics of the site, what it looks like, and the artifacts researchers have found there. To begin, he explains that the site is made up of several low-lying mounds that span 22 hectares (Heibert). Ceramic scatter and sherds can be found all over the area, and these, along with other artifacts found, show variances (in the materials from which they were made) based on the specific regions they were found. The architecture of the Gonur-depe site is also worth noting, and Heibert discusses one building, called the kremel, in particular. This building was excavated by Heibert from 1981 till 1983. The kremel exhibits strong external walls and carefully designed linear internal rooms. Burials and cenotaphs widely surround this structure as well (Heibert).

Heibert also conducted a deep sounding stratigraphic excavation of Gonur North in 1989, although his analysis of the different layers is not presented with dates. Although he does provide a reason for not being able to date the top layer (surface level objects can be windblown so dating is difficult in multiperiod sites), he does not provide reasons for not being able to date the other layers. However, his analysis of the different layers – there being 7 in total – did provide some insight into people’s lives who lived there at the time. For example, Heibert states that in layers 3 and 4, evidence of fragments from a kiln or oven were found (Heibert).

Transitioning from overall structure and artifacts found at Gonur-depe, Kufterin’s paper, “A preliminary analysis of Late Bronze Age human skeletal remains from Gonur-depe, Turkmenistan” delves into providing a summary on the paleopathology of the population, made up of 920 individuals, whose remains were found at the Gonur Ruins. The researchers are also careful to differentiate between the Gonur Ruins and Gonur’s necropolis. The former refers to burials found directly in the walls of the architectural structures, while the latter refers to a large cemetery. In Gonur’s necropolis, the burial constructions are looked at closely. Specifically, of all the burials in Gonur-depe necropolis, more than half are shaft graves, which are either oval or rectangular wells with a depth of about one or two meters (Molodin). As for the burials from Gonur’s ruins, however, researchers state that they mostly date back to the last period of Gonur’s existence (Kufterin).

Aerial View of Gonur-depe. Photo From Lawler 2006.

As for their findings, Kufterin implements macroscopic investigation in order to compile and discuss the common paleopathological conditions that they find evidence for: dental abscesses and antemortem tooth loss (AMTL), cribra orbitalia, traumatic injuries, degenerative joint diseases and infectious processes (Kufterin). In comparing the frequency of these paleopathologies from the Gonur Ruins to the necropolis, researchers ultimately found that most of these conditions were more prevalent in the latter location. As a result, they conclude that the population that inhabited Gonur–depe towards the end of its existence was well adapted to not only their lifestyles but also their environmental conditions.

Transitioning, once again, from the specifics of paleopathologies and burial sites to artifacts found at the Gonur-depe site allow for a different perspective of understanding of time period in which this site was inhabited as well as its ties to other parts of the world. Archeologist D.T Potts discusses these topics via his discovery of an Umm an-Nar-type vessel found in the Gonur-depe site. For context, Umm-an-Nar refers to a period of history in the Oman peninsula at around 2500 BC (al-Jahwari).Pott’s article describes the presence of typical Umm-an-Nar-type, rectangular, compartmented vessel that had two rows of five double-dotted circles on either sides. This vessel was found in one of the graves at the Gonur-depe burial excavation sites.

Potts 2008.

Potts uses this discovery to encourage other scholars to acknowledge the possibility of contact between the Bactria, Margiana, and eastern Arabia (Potts). He proceeds to include possible routes that people might have taken in order to travel from Oman to present day Turkemenistan, and though he can not definitively prove these routes existed, he does state that the Umm-an-Nar-type vessel at Gonur-depe, and other finds like it, support the theory of interconnectedness between societies and their cultures in the Bronze Age era.

Hopefully, research in the Gonur-depe and surrounding Turkmenistan region will continue in order to more fully build a picture of what life in this ancient civilization along the Murghab River was like. Though the architecture, pathologies, burial rituals, and artifacts discussed above begin to paint a picture, Gonur-depe can definitely be better understood and contextualized within a larger prehistoric Central Asia context.

Sources:

Al-Jahwari, Nasser Said. “The Agricultural Basis of Umm An-Nar Society in the Northern Oman Peninsula (2500-2000 BC).” Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 20.2 (2009): 122-33.

Hiebert, Fredrik Talmage., C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky, and Viktor Ivanovič. Sarianidi. Origins of the Bronze Age: Oasis Civilization in Central Asia. Cambridge, MA: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 1994

Kufterin, Vladamir, and Nadezhda Dubova. “A Preliminary Analysis of Late Bronze Age Human Skeletal Remains from Gonur-depe, Turkmenistan.” Bioarchaeology of the Near East 7.33 (2013): 33-46.

Lawler, Andrew. “Central Asia’s Lost Civilization.” Andrew Lawler. WordPress, 23 Nov. 2006.

Potts, D.t. “An Umm An-Nar-type Compartmented Soft-stone Vessel from Gonur Depe, Turkmenistan.” Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 19.2 (2008): 168-81.

Кузьминой, Елена Ефимовны. “Арии Степей Евразии: Эпоха Бронзы И Раннего Железа В Степях Евразии И На Сопредельных Территориях.” Барнаул: Издательство Алтайского Государственного универцитета, 2014. **

**My last source is the one I translated in Russian and is cited in my text using the editor’s last name, Molodin. The English name of the book is: THE ARYANS IN THE EURASIAN STEPPES: THE BRONZE AND EARLY IRON AGES IN THE STEPPES OF EURASIA AND CONTIGUOUS TERRITORIES.

Tepe Hissar

May 9, 2017

Alternate spellings: Tappa Hesār, Tapeh Hesar, Tappeh Hesar, Tappe Hesar

The site of Tepe Hissar was an important location in Central Asia during the Late Neolithic time period and leading up to the Iron Age. It is located in northeastern Iran, just south of the city of Damghan. It experienced three major periods of inhabitation, and is known for its burnished grey pottery and lapis lazuli bead-working.

The first excavation of Tepe Hissar was led by Erich F. Schmidt in 1931-1932 on behalf of University of Pennsylvania Museum. There were two seasons of excavation, the first from July to mid-November in 1931 and the second from May through November in 1932. While Schmidt’s main objective in these excavations was to uncover more information about Tepe Hissar, he was also preoccupied with having to provide artifacts for the sponsoring museums in Pennsylvania and Tehran, which would be split 50/50 as according to the revised Iranian Antiquities Law. He often accredited signs of cultural change to the invasion of foreign ethnic groups, as was typical of anthropologists during this time period. There was another excavation organized in 1976 by the University of Pennsylvania Museum, Turin University, and the Iran Center for Archaeological Research (Gürsan-Salzmann, 2016).

Schmidt divided the stratigraphy of the site into three parts: Hissar I, Hissar II, and Hissar III. The starting point of Hissar I is slightly unclear, but is recognized as having occurred after 5,000 BCE. The second period, Hissar II, is dated from the 4th millennium to the beginning of the 3rd millennium BCE. It is believed that Hissar III ended before the Iron Age, and most sources place the end of occupation at Tepe Hissar at sometime in the first half of the second millennium BCE (Voigt and Dyson, 1992). This is evidenced by the absence of iron in Hissar III (Gürsan-Salzmann, 2016). While Schmidt relied heavily on ceramic findings in dating the various periods of human occupation at Tepe Hissar, more modern techniques, such as radiocarbon dating, have provided more accurate boundaries between the periods. For example, radiocarbon samples have provided a range of between 2800 to 2400 BCE for the Hissar III time period (Bovington, 1974). The dates of these time periods have also been largely inferred through looking at other sites in the area, which has resulted in some confusion but has also been fairly effective. For example, many of the metal and stone artifacts found resemble those of the Early Dynastic period in Mesopotamia, while others appear to belong more to the Akkadian or Ur III periods. This means that the objects date between 2500 BCE to 2100 BCE (Gordon, 1951).

Small amounts of calcite and steatite found with artifacts signifying various stages of bead-making. Additionally, there were bits of lapis and flint blades and drills found throughout the site, indicating that the manipulation of precious stones was a viable industry. An abundance of small clay and alabaster animals was also found, which Schmidt attributed to both spiritual and utilitarian uses. Clay “stamp seals” with geometric designs were also uncovered, but there is a lack of evidence of imprints of the stamps, leading anthropologists to believe that they could be small ornaments or buttons instead. The lack of evidence could also be explained by how hastily the excavators were working. However, one “stamp seal” of interest depicted two human figures, an ibex, and snakes. This incorporation of human figures into geometric and animal designs was very unusual for the Hissar I time period (Gürsan-Salzmann, 2016).

Figure 1: Three alabaster animal figures found in grave “Warrior 2″(Penn Museum, object nos. 33-15-526, 33-15-525, 33-15-524) (Photo by Jason Francisco)

The burials at Tepe Hissar were mostly found on the Main Mound and North Flat areas. Three main types of burials were identified. Most of the bodies were buried in the “pit” style, or they were wrapped in wool clothes and interred in a pit. “Cist graves” were burials within enclosures, and the objects buried with the dead are often indicative of more wealth. There were also “communal chamber burials,” ranging from two to 28 individuals. Both the “cist graves” and the “communal chamber burials” are much more uncommon than the “pit” graves. Schmidt also identified four especially wealthy graves that were discovered, which he labeled “warrior 1,” “dancer,” “little girl,” and “priest.” These individuals were buried with metal weapons, agricultural tools, and domestic utensils, including stone and copper seals, a “fan”/mirror, small clay animal sculptures, and copper, silver, and alabaster female figurines (Gürsan-Salzmann, 2016).

Figure 2: GIS map of Tepe Hissar, showing the burials concentrated in the Main Mound and North Flat areas (Gürsan-Salzmann, 2016; Kılınç Ünlü and Torres, 2010)

The people who occupied Tepe Hissar are often referred to as belonging to the Hissar, Gurgan, or Eastern Grey Ware culture. They are believed to have assisted communication and contact throughout Iran and Mesopotamia, especially towards the end of the Bronze Age (Bovington, 1974). According to The Great Soviet Encyclopedia, the Hissar culture “represents a culture, archaic in appearance, of tribes of the foothills and mountain valleys that evidently developed at the same time as the more developed, settled farming cultures in other parts of Middle Asia.” This definition reveals ideological biases related to the supposed “underdeveloped” nature of Central Asian cultures in comparison to more northern settlements. In looking at archaeological evidence, the economy of Tepe Hissar was based on agriculture. Plant remains indicate “an agricultural system based on cereals [glume and free-threshing wheats, naked and hulled barley] and the utilization of local fruit [olive, grapevine] plant resources” (Costantini and Dyson, p. 66). Some of the clay figures were cattle and sheep, indicating herding activities (Mashkour, 1996).

The site of Tepe Hissar is clearly visible on Google Earth. The coordinates are 36°09’16.13″ N 54°22’59.30″E and the elevation is approximately 3,679 feet. The site is cut in half by what seems to be a paved road, and half of the site is enclosed within another curving road.

Works Cited

Bovington, C. H., Jr., R. H., Mahdavi, A., & Masoumi, R. (1974). The Radiocarbon Evidence for the Terminal Date of the Hissar IIIC Culture. Iran, 12, 195. doi:10.2307/4300513